Marina Warner in the LRB (photo from Wikipedia):

Marina Warner in the LRB (photo from Wikipedia):

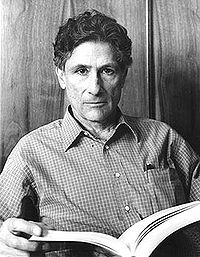

Edward Said first met Daniel Barenboim by chance, at the reception desk of the Hyde Park Hotel in June 1993; Said mentioned he had tickets for a concert Barenboim was playing that week. They began to talk. Six years later, in Weimar, they dreamed up the idea of a summer school in which young musicians from the Arab world and from Israel could play together. They hoped, Said remembered in Parallels and Paradoxes, that it ‘might be an alternative way of making peace’. It was in Weimar, he noted, that Goethe had composed ‘a fantastic collection of poems based on his enthusiasm for Islam … He started to learn Arabic, although he didn’t get very far. Then he discovered Persian poetry and produced this extraordinary set of poems about the “other”, West-östlicher Divan, which is, I think, unique in the history of European culture.’ The West-Eastern Divan: the orchestra had a name; it was never discussed again.

It seems odd that Said, the fierce critic of European Orientalism, chose to use the title of a work that, on the face of it, belongs in the Orientalist tradition. Goethe’s poems are filled with roses and nightingales, boys beautiful as the full moon, wine, women and song. Yet as Said saw it, Goethe’s lyric cycle is animated by a spirit of open inquiry towards the East, grounded in a sense of the past in art and culture, not in dogma or military and state apparatuses. He read it as calling for an understanding of individuality as a process of becoming and therefore fluid. He also believed that poetry can have the metaphorical power to proclaim a visionary politics. The cycle represented for him an alternative history and epistemology, concerned with the cross-pollination between East and West. It seemed to confirm the orchestra’s principle that ‘ignorance of the other is not a strategy for survival.’

Said’s approach was always historical; his work as a critic and intellectual was rooted in an examination of context, both cultural and political, and the orchestra, which this summer toured South America, embodies his commitment to the work of art as an actor in its time. The word theoria, he liked to remind us, means ‘the action of observing’; for him, theory was a dynamic, engaged activity, not a matter of passive reception. The theorist-critic should be a committed participant in the works he observes, and the works themselves aren’t self-created or autonomous but precipitated in the crucible of society and history. ‘My position is that texts are worldly,’ he writes in The World, the Text and the Critic. ‘To some degree they are events, and, even when they appear to deny it, they are nevertheless a part of the social world, human life, and of course the historical moments in which they are located and interpreted.’ The making of music is an event in this sense too.

Julia Ioffe in Foreign Policy:

Julia Ioffe in Foreign Policy:

When journalists showed up to hear the judge read the long-awaited verdict in the case of jailed oil tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovsky, they found a note on the courthouse door. The reading of the verdict, it said, would be postponed. It was still early in the morning, though, and the note — unsigned and typewritten — seemed like it could easily be fake. This was, after all, the denouement of a highly politicized, hyper-publicized trial, both in Russia and abroad. So one of the puzzled journalists called Khodorkovsky's lawyer, Genrikh Padva, who had not yet heard of the note's existence. “I might have expected this,” he said. “But no one warned me about it ahead of time.”

By the time Padva got to the courthouse, there was a scrum of reporters and elderly Khodorkovsky supporters by the door. They swarmed him, demanding an explanation. “Apparently the court just didn't have enough time to write the verdict,” the lawyer explained. He also had not gotten an official explanation (just an official version of the note on the door) but Padva and the rest of the legal team tried to play it down. This happens all the time, they said. Only Khodorkovsky's father, Boris, had a more probing — and Russian — explanation: After the delay, he said, “a lot fewer people will come” for the actual verdict.

The date was April 27, 2005.

Five and a half years later, on December 15, journalists awaited another Khodorkovsky verdict; the scene was almost identical, with a few names and details changed around. It was a different Moscow courthouse and a different case in question, this one brought in 2007 when Khodorkovsky and his partner Platon Lebedev were just about to be up for parole. The new charges alleged that the two stole all the oil their company Yukos ever produced and then laundered the ill-begotten proceeds. (The first case was that they neglected to pay taxes on this laundered oil money. The apparent contradiction between these two cases has yet to be explained.)

Ian Johnson in the NYRB blog:

Ian Johnson in the NYRB blog:

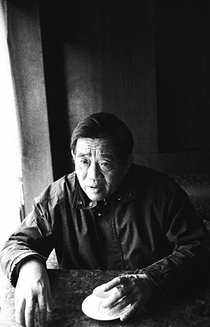

Yang Jisheng is an editor of Annals of the Yellow Emperor, one of the few reform-oriented political magazines in China. Before that, the 70-year-old native of Hubei province was a national correspondent with the government-run Xinhua news service for over thirty years. But he is best known now as the author of Tombstone (Mubei), a groundbreaking new book on the Great Famine (1958–1961), which, though imprecisely known in the West, ranks as one of worst human disasters in history. I spoke with Yang in Beijing in late November about his book, the political atmosphere in Beijing, and the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo.

Tombstone, which Yang began working on when he retired from Xinhua in 1996, is the most authoritative account of the Great Famine. It was caused by the Great Leap Forward, a millennial political campaign aimed at catapulting China into the ranks of developed nations by abandoning everything (including economic laws and common sense) in favor of steel production. Farm work largely stopped, iron tools were smelted in “backyard furnaces” to make steel—most of which was too crude to be of any use—and the Party confiscated for city dwellers what little grain was sown and harvested. The result was one of the largest famines in history. From the government documents he consulted, Yang concluded that 36 million people died and 40 million children were not born as a result of the famine. Yang’s father was among the victims and Yang says this book is meant to be his tombstone.

From Salon:

A set of drawers in Philadelphia's Mütter Museum of human pathology contains some very curious artifacts: thousands of objects, from umbrella tips to diminutive opera glasses, that have been extracted from the human body. They were swallowed or inhaled (sometimes accidentally, sometimes on purpose) and later removed by Dr. Chevalier Jackson, a man who dedicated much of his life to removing odd objects from people's insides. The collection is a remarkable testament to the strangeness of the human experience — and our ability to swallow.

A set of drawers in Philadelphia's Mütter Museum of human pathology contains some very curious artifacts: thousands of objects, from umbrella tips to diminutive opera glasses, that have been extracted from the human body. They were swallowed or inhaled (sometimes accidentally, sometimes on purpose) and later removed by Dr. Chevalier Jackson, a man who dedicated much of his life to removing odd objects from people's insides. The collection is a remarkable testament to the strangeness of the human experience — and our ability to swallow.

In her new book, “Swallow,” Mary Cappello uncovers the stories behind those objects, and the peculiar life story of Chevalier himself. Cappello is a professor at the University of Rhode Island and the author of the bestselling book “Awkward,” a meditation on uncomfortableness. Here, she packs her story with surprising imagery and extravagant lyricism, taking a highly literary approach to the subject — meandering from Chevalier's biography to the odd story of early 1920s women who compulsively ingested pieces of hardware.

More here.

From The New York Times:

Young female chimpanzees like to play with sticks as if they were dolls, according to a new study in the journal Current Biology. Although both juvenile male and female chimpanzees were seen playing with sticks in Kibale National Park in Uganda, females were more likely to cradle the sticks and treat them like infants. In human children, societal stereotypes may dictate what boys and girls play with, said Sonya Kahlenberg, a biologist at Bates College in Maine and one of the study’s authors. “The monkeys tell us there is something different there,” she said. The researchers studied juvenile behavior in a single chimpanzee colony over 14 years, and observed 15 females and 16 males.

Young female chimpanzees like to play with sticks as if they were dolls, according to a new study in the journal Current Biology. Although both juvenile male and female chimpanzees were seen playing with sticks in Kibale National Park in Uganda, females were more likely to cradle the sticks and treat them like infants. In human children, societal stereotypes may dictate what boys and girls play with, said Sonya Kahlenberg, a biologist at Bates College in Maine and one of the study’s authors. “The monkeys tell us there is something different there,” she said. The researchers studied juvenile behavior in a single chimpanzee colony over 14 years, and observed 15 females and 16 males.

Of the 15 females, 10 carried around sticks, while five of the males were seen with sticks. The young females were apparently mimicking their mothers, she said. “Females are the main caretakers,” Dr. Kahlenberg said. “Though it’s not that we didn’t see that in male chimps at all.” In one instance, an eight-year-old male with a stick stepped out of his mother’s nest, built a smaller nest and laid his stick in it. Although adult chimpanzees are also known to use sticks, they use them as foraging tools, not toys. Juveniles were defined as chimpanzees between the ages of five and 7.9. This is roughly equivalent to the human age range of six to nine, Dr. Kahlenberg said.

More here.

Monday, December 20, 2010

Yayoi Kusama. Fireflies on the Water.

Installation, 2002.

More here, here, and here.

Sunday, December 19, 2010

Michael Shermer in Big Question:

Michael Shermer in Big Question:

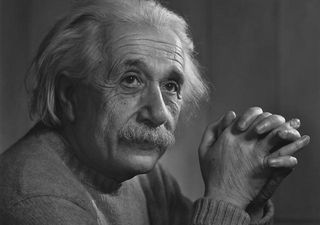

What did Einstein mean by “God” playing dice, or “us believing physicists”? Was he speaking literally or metaphorically? Did he mean belief in the models of theoretical physics that make no distinction between past, present, and future? Did he mean belief in some impersonal force that exists above such time constraints? Was he just being polite and consoling to Besso’s family? Such is the enigma of the most well-known scientist in history whose fame was such that nearly everything he wrote or said was scrutinized for its meaning and import; thus, it is easy to yank such quotes out of context and spin them in any direction one desires.

When he turned 50, Einstein granted an interview in which he was asked point-blank, do you believe in God? “I am not an atheist,” he began. “The problem involved is too vast for our limited minds. We are in the position of a little child entering a huge library filled with books in many languages. The child knows someone must have written those books. It does not know how. It does not understand the languages in which they are written. The child dimly suspects a mysterious order in the arrangement of the books but doesn’t know what it is. That, it seems to me, is the attitude of even the most intelligent human being toward God. We see the universe marvelously arranged and obeying certain laws but only dimly understand these laws.”

That almost sounds like Einstein is attributing the laws of the universe to a god of some sort. But what type of god? A personal deity or some impersonal force? To a Colorado banker who wrote and asked him the God question, Einstein responded: “I cannot conceive of a personal God who would directly influence the actions of individuals or would sit in judgment on creatures of his own creation. My religiosity consists of a humble admiration of the infinitely superior spirit that reveals itself in the little that we can comprehend about the knowable world. That deeply emotional conviction of the presence of a superior reasoning power, which is revealed in the incomprehensible universe, forms my idea of God.”

The most famous Einstein pronouncement on God came in the form of a telegram, in which he was asked to answer the question in 50 words or less. He did it in 32: “I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the lawful harmony of all that exists, but not in a God who concerns himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.”

Tyler Burge in the NYT:

Tyler Burge in the NYT:

Imagine that reports of the mid-20th-century breakthroughs in biology had focused entirely on quantum mechanical interactions among elementary particles. Imagine that the reports neglected to discuss the structure or functions of DNA. Inheritance would not have been understood. The level of explanation would have been wrong. Quantum mechanics lacks a notion of function, and its relation to biology is too complex to replace biological understanding. To understand biology, one must think in biological terms.

Discussing psychology in neural terms makes a similar mistake. Explanations of neural phenomena are not themselves explanations of psychological phenomena. Some expect the neural level to replace the psychological level. This expectation is as naive as expecting a single cure for cancer. Science is almost never so simple. See John Cleese’s apt spoof of such reductionism.

The third thing wrong with neurobabble is that it has pernicious feedback effects on science itself. Too much immature science has received massive funding, on the assumption that it illuminates psychology. The idea that the neural can replace the psychological is the same idea that led to thinking that all psychological ills can be cured with drugs.

Correlations between localized neural activity and specific psychological phenomena are important facts. But they merely set the stage for explanation. Being purely descriptive, they explain nothing. Some correlations do aid psychological explanation. For example, identifying neural events underlying vision constrains explanations of timing in psychological processes and has helped predict psychological effects. We will understand both the correlations and the psychology, however, only through psychological explanation.

Frederic Lezmi in lensculture:

I have been searching for the “in between” – whatever lies geographically as well as culturally between my world here in the midst of Europe and my long term focus of interest in the Middle and Near East. Being half Lebanese myself, I have been studying cultural interfaces within the distant Arabic World. From August to December 2008 I traveled between Vienna and Beirut. I encountered people in versatile worlds, inside or in front of architectural places, both real and artificial, public and private. In my photographs, people emerge either as just passers-by or while waiting, as subjects and objects of the viewer’s eye, moving about in their urban or rural environment. These are distanced views in which locals and tourists are on similar paths, randomly congregating and forming elusive compositions. These pictures represent neither precise documents nor do they create artistic worlds. They are constructions of multicolored, fragmented impressions, like looking through a kaleidoscope.

I have been searching for the “in between” – whatever lies geographically as well as culturally between my world here in the midst of Europe and my long term focus of interest in the Middle and Near East. Being half Lebanese myself, I have been studying cultural interfaces within the distant Arabic World. From August to December 2008 I traveled between Vienna and Beirut. I encountered people in versatile worlds, inside or in front of architectural places, both real and artificial, public and private. In my photographs, people emerge either as just passers-by or while waiting, as subjects and objects of the viewer’s eye, moving about in their urban or rural environment. These are distanced views in which locals and tourists are on similar paths, randomly congregating and forming elusive compositions. These pictures represent neither precise documents nor do they create artistic worlds. They are constructions of multicolored, fragmented impressions, like looking through a kaleidoscope.

More here.

From The Telegraph:

It is not hard to think of examples of wide-eyed predictions that have proved somewhat wide of the mark. Personal jetpacks, holidays on the moon, the paperless office and the age of leisure all underline how futurologists are doomed to fail. Any predictions should thus be taken with a heap of salt, but that does not mean crystal ball-gazing is worthless: on the contrary, even if it turns out to be bunk, it gives you an intriguing glimpse of current fads and fascinations. A few weeks ago, a science festival in Genoa, Italy, gathered together some leading lights to discuss the one aspect of futurology that excites us all: cosa farà cambiare tutto — this will change everything. The event was organised by John Brockman, a master convener, both online and in real life, and founder of the Edge Foundation, a kind of crucible for big new ideas. With him were two leading lights of contemporary thought: Stewart Brand, the father of the Whole Earth Catalog, co-founder of a pioneering online community called The Well and of the Global Business Network; and Clay Shirky, web guru and author of Cognitive Surplus: Creativity and Generosity in a Connected Age.

It is not hard to think of examples of wide-eyed predictions that have proved somewhat wide of the mark. Personal jetpacks, holidays on the moon, the paperless office and the age of leisure all underline how futurologists are doomed to fail. Any predictions should thus be taken with a heap of salt, but that does not mean crystal ball-gazing is worthless: on the contrary, even if it turns out to be bunk, it gives you an intriguing glimpse of current fads and fascinations. A few weeks ago, a science festival in Genoa, Italy, gathered together some leading lights to discuss the one aspect of futurology that excites us all: cosa farà cambiare tutto — this will change everything. The event was organised by John Brockman, a master convener, both online and in real life, and founder of the Edge Foundation, a kind of crucible for big new ideas. With him were two leading lights of contemporary thought: Stewart Brand, the father of the Whole Earth Catalog, co-founder of a pioneering online community called The Well and of the Global Business Network; and Clay Shirky, web guru and author of Cognitive Surplus: Creativity and Generosity in a Connected Age.

Shirky meditated on how, during his formative years, it was thought that the decades to come would be dominated by nuclear power and the great adventure of space flight. Decades later, it is now clear that those technologies may have dominated discussions of the day but their direct influence remained firmly with the technological elite. With the benefit of hindsight, his early years were the age of the transistor and birth control. When it comes to the forces shaping our lives today, Shirky points to how coordinated voluntary participation is on the rise, thanks to online tools. With the help of the internet, people are now learning how to make use of the increasing amounts of free time that have been afforded to them since the 1940s for creative acts rather than consumptive ones.

More here.

A Letter in October

Dawn comes later and later now,

and I, who only a month ago

could sit with coffee every morning

watching the light walk down the hill

to the edge of the pond and place

a doe there, shyly drinking,

then see the light step out upon

the water, sowing reflections

to either side—a garden

of trees that grew as if by magic—

now see no more than my face,

mirrored by darkness, pale and odd,

startled by time. While I slept,

night in its thick winter jacket

bridled the doe with a twist

of wet leaves and led her away,

then brought its black horse with harness

that creaked like a cricket, and turned

the water garden under. I woke,

and at the waiting window found

the curtains open to my open face;

beyond me, darkness. And I,

who only wished to keep looking out,

must now keep looking in.

by Ted Kooser

from Weather Central

University of Pittsburgh Press

Copyright 1994

Saturday, December 18, 2010

Geert Lovink and Patrice Riemens in Eurozine:

Thesis 5

The steady decline of investigative journalism caused by diminishing funding is an undeniable fact. Journalism these days amounts to little more than outsourced PR remixing. The continuous acceleration and over-crowding of the so-called attention economy ensures there is no longer enough room for complicated stories. The corporate owners of mass circulation media are increasingly disinclined to see the workings and the politics of the global neoliberal economy discussed at length. The shift from information to infotainment has been embraced by journalists themselves, making it difficult to publish complex stories. WikiLeaks enters this state of affairs as an outsider, enveloped by the steamy ambiance of “citizen journalism”, DIY news reporting in the blogosphere and even faster social media like Twitter. What WikiLeaks anticipates, but so far has been unable to organize, is the “crowd sourcing” of the interpretation of its leaked documents. That work, oddly, is left to the few remaining staff journalists of selected “quality” news media. Later, academics pick up the scraps and spin the stories behind the closed gates of publishing stables. But where is networked critical commentariat? Certainly, we are all busy with our minor critiques; but it remains the case that WikiLeaks generates its capacity to inspire irritation at the big end of town precisely because of the transversal and symbiotic relation it holds with establishment media institutions. There's a lesson here for the multitudes – get out of the ghetto and connect with the Oedipal other. Therein lies the conflictual terrain of the political.

Over at Eurekalert:

Science and its publisher, AAAS, the nonprofit science society, have recognized this first quantum machine as the 2010 Breakthrough of the Year. They have also compiled nine other important scientific accomplishments from this past year into a top ten list, appearing in a special news feature in the journal's 17 December 2010 issue. Additionally, Science news writers and editors have chosen to spotlight 10 “Insights of the Decade” that have transformed the landscape of science in the 21st Century.

“This year's Breakthrough of the Year represents the first time that scientists have demonstrated quantum effects in the motion of a human-made object,” said Adrian Cho, a news writer for Science. “On a conceptual level that's cool because it extends quantum mechanics into a whole new realm. On a practical level, it opens up a variety of possibilities ranging from new experiments that meld quantum control over light, electrical currents and motion to, perhaps someday, tests of the bounds of quantum mechanics and our sense of reality.”

The quantum machine proves that the principles of quantum mechanics can apply to the motion of macroscopic objects, as well as atomic and subatomic particles. It provides the key first step toward gaining complete control over an object's vibrations at the quantum level. Such control over the motion of an engineered device should allow scientists to manipulate those minuscule movements, much as they now control electrical currents and particles of light. In turn, that capability may lead to new devices to control the quantum states of light, ultra-sensitive force detectors and, ultimately, investigations into the bounds of quantum mechanics and our sense of reality. (This last grand goal might be achieved by trying to put a macroscopic object in a state in which it's literally in two slightly different places at the same time—an experiment that might reveal precisely why something as big as a human can't be in two places at the same time.)

A few years ago, when I was still teaching at the University of Chicago, I had my first Chinese graduate students, a couple of earnest Beijingers who had come to the Committee on Social Thought hoping to bump into the ghost of Leo Strauss, the German-Jewish political philosopher who established his career at the university. Given the mute deference they were accustomed to giving their professors, it was hard to make out just what these young men were looking for, in Chicago or Strauss. They attended courses and worked diligently, but otherwise kept to themselves. They were in but not of Hyde Park. At the end of their first year, I called one of them into my office to offer a little advice. He was obviously thoughtful and serious, and was already well known in Beijing intellectual circles for his writings and his translations of Western books in sociology and philosophy into Chinese. But his inability to express himself in written or spoken English had frustrated us both in a course of mine he had just taken. I began asking about his summer plans, eventually steering the conversation to the subject of English immersion programs, which I suggested he look into. “Why?” he asked. A little flummoxed, I said the obvious thing: that mastering English would allow him to engage with foreign scholars and advance his career at home. He smiled in a slightly patronizing way and said, “I am not so sure.” Now fully flummoxed, I asked what he would be doing instead. “Oh, I will do language, but Latin, not English.” It was my turn to ask why. “I think it very important we study Romans, not just Greeks. Romans built an empire over many centuries. We must learn from them.” When he left, it was clear that I was being dismissed, not him.

more from Mark Lilla at TNR here.

If the pram in the hall is the enemy of good art, what happens when the babies grow up and the pram is replaced by a Zimmer frame? Until recently, most women did not live long enough for us to find out. But now old age among female artists and writers is the new chic, as increased longevity trumps the time-worn complaint that after 50 a woman is socially and professionally invisible. In the 21st century, creative women in their eighties and nineties such as Louise Bourgeois (born 1911), Leonora Carrington (born 1917) and Diana Athill (born 1917) emerged from the tunnel of obscure middle-age to become glamorous if not household, at least drawing-room names. In 2010 the prominence of such figures in the visual arts became inescapable. The National Gallery in London is currently showing 79-year-old Bridget Riley’s engagement with the Old Masters (to May 22). At Frankfurt’s Städel Museum the furious neo-expressionist work of 91-year-old Austrian Maria Lassnig concludes a survey of paintings from the 14th to the 21st centuries (to June 26). In Paris, the most flamboyant installation in the Tuileries for this autumn’s FIAC was the mirrored sculpture “Narcissus Garden” by Yayoi Kusama, who is 81 and lives in a Tokyo mental hospital. Surreal Friends, a British touring exhibition which closed last week, introduced 93-year-old English-Mexican artist Carrington’s menacing surreal paintings to a wide new audience.

more from Jackie Wullschlager at the FT here.

Take heart, readers. A Pew Internet & American Life Project report released this month found that just “[e]ight percent of the American adults who use the Internet are Twitter users.” I can’t be the only one to find this heartening in a culture awash in instant information, in the slings and arrows of the 140- character tweet. For a long time, I’ve regarded Twitter as the ultimate expression of our shared distraction, a virtual game of telephone in which the chatter is by its nature reductive, stripped of complexity, nuance, all those subtle shades of gray. And yet, what may be most interesting about the Pew study is its timing, since this is the year e-readers took off. What does it say about us that, on the one hand, we don’t seem so enthralled by the hit-and-run of Twitter while on the other, we can’t get enough of electronic books? Only this: that technology is not a barrier to depth, to engagement, to the cultural discussion, and that perhaps we want the same thing from our reading as we always have, regardless of the form it takes. E-books, after all, are the story in publishing this year, with more than seven million iPads sold in the eight months since the device went on sale in April, joining millions of Kindles, Sony Readers, Kobos and Nooks. Just a week or so ago, Google launched Google Editions, an e-book retailer designed to compete with the iBook and Kindle stores.

more from David L. Ulin at the LA Times here.

Marina Warner in the LRB (photo from Wikipedia):