Yascha Mounk in his own Substack:

So far, we humans have mostly restricted ourselves to the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI). The SETI Institute, a private, nonprofit research organization, has built a variety of instruments designed to detect signs of extraterrestrial life. So have other institutes and universities. This activity is reasonably uncontroversial: If somebody is trying to send us a message, it would likely be beneficial to receive it; we can then figure out how, and whether, to answer.

So far, we humans have mostly restricted ourselves to the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI). The SETI Institute, a private, nonprofit research organization, has built a variety of instruments designed to detect signs of extraterrestrial life. So have other institutes and universities. This activity is reasonably uncontroversial: If somebody is trying to send us a message, it would likely be beneficial to receive it; we can then figure out how, and whether, to answer.

But over the past few years, a number of scientists have proposed that we should go beyond SETI. Disappointed that we have not yet discovered any extraterrestrial life through the passive act of listening, they insist that we should take more active steps to broadcast our existence to the outside world and enter into communication with aliens.

Some believers in what has come to be known as Messaging to ExtraTerrestrial Intelligence (METI) have started to take matters into their own hands.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

W

W

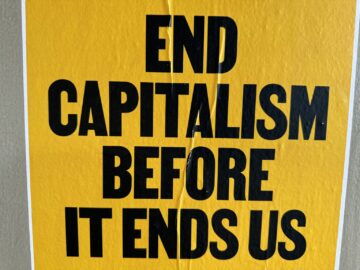

In the wake of his huge defeat on June 30, 2024, when 80 percent of voters rejected French “centrist” President Emmanuel Macron, he said he understood the French people’s anger. In the UK, Conservative loser Rishi Sunak said the same about the British people’s anger, as Labor leader Starmer now says as the anger explodes. Of course, such phrases from such politicians usually mean little or nothing and accomplish less. Such leaders and their parties just keep calculating how best to regain power when they lose it. In that, they are like the U.S. Democrats after Biden’s performance in his debate with Trump and like the U.S. Republicans after Trump’s loss in 2020. In both parties, a small group of top leaders and top donors made all the key decisions and then organized the political theater to ratify those decisions. Even surprises like Harris replacing Biden are temporary departures from resuming politics as usual.

In the wake of his huge defeat on June 30, 2024, when 80 percent of voters rejected French “centrist” President Emmanuel Macron, he said he understood the French people’s anger. In the UK, Conservative loser Rishi Sunak said the same about the British people’s anger, as Labor leader Starmer now says as the anger explodes. Of course, such phrases from such politicians usually mean little or nothing and accomplish less. Such leaders and their parties just keep calculating how best to regain power when they lose it. In that, they are like the U.S. Democrats after Biden’s performance in his debate with Trump and like the U.S. Republicans after Trump’s loss in 2020. In both parties, a small group of top leaders and top donors made all the key decisions and then organized the political theater to ratify those decisions. Even surprises like Harris replacing Biden are temporary departures from resuming politics as usual. Dear Tom,

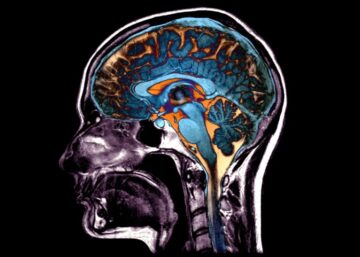

Dear Tom, An analysis of almost 50,000 brain scans

An analysis of almost 50,000 brain scans

Schmidt confessed to revising his AI outlook every six months, a testament to the field’s volatility. He shared a striking example: “Six months ago, I was convinced that the gap [between frontier AI models and the rest] was getting smaller, so I invested lots of money in the little companies. Now I’m not so sure.”

Schmidt confessed to revising his AI outlook every six months, a testament to the field’s volatility. He shared a striking example: “Six months ago, I was convinced that the gap [between frontier AI models and the rest] was getting smaller, so I invested lots of money in the little companies. Now I’m not so sure.” America’s most curious endeavors: Atoms for Peace and its policy that spread dangerous nuclear technology world-wide.

America’s most curious endeavors: Atoms for Peace and its policy that spread dangerous nuclear technology world-wide. Though it’s true that sadness in its many forms was one of Smith’s central preoccupations, neither he nor his music were defined by it. The spare waltz that defeats Tiny Rick appears on Smith’s third solo album, 1997’s Either/Or. It’s played acoustically at an unhurried pace and combines a seductive lyric about finding solace in booze with a melody that perfectly captures its quiet desperation. In the chorus, a dark E-flat minor hits you like a gut punch because your ears expect a more optimistic E-flat major, and the song returns to that unstable chord to finish, denying you any conventional harmonic resolution. It’s a masterly composition that eclipses anything by Smith’s own idols, including the Beatles or Elvis Costello – sad, yes, but too wondrous to feel strictly morose. And he didn’t write it strung out and crying into an empty glass of Jameson. It was apparently knocked into shape while he was watching the swords-and-sandals TV show Xena: Warrior Princess.

Though it’s true that sadness in its many forms was one of Smith’s central preoccupations, neither he nor his music were defined by it. The spare waltz that defeats Tiny Rick appears on Smith’s third solo album, 1997’s Either/Or. It’s played acoustically at an unhurried pace and combines a seductive lyric about finding solace in booze with a melody that perfectly captures its quiet desperation. In the chorus, a dark E-flat minor hits you like a gut punch because your ears expect a more optimistic E-flat major, and the song returns to that unstable chord to finish, denying you any conventional harmonic resolution. It’s a masterly composition that eclipses anything by Smith’s own idols, including the Beatles or Elvis Costello – sad, yes, but too wondrous to feel strictly morose. And he didn’t write it strung out and crying into an empty glass of Jameson. It was apparently knocked into shape while he was watching the swords-and-sandals TV show Xena: Warrior Princess. We’re publishing these exchanges just about every two weeks—a compressed timeline that somehow seems like an eternity amid this summer’s news cycles. Thankfully, art offers its own distinct time signature. When we look at a painting or read a poem, we don’t escape from time, but we do experience it differently. Time contracts and dilates; it folds in and out; mere sequence becomes pattern, shape, meaning. “You are the music / While the music lasts,” as T. S. Eliot puts it. This temporal re-shuffling is one of the gifts of art, and it’s one that I’m especially appreciating during this frenetic summer.

We’re publishing these exchanges just about every two weeks—a compressed timeline that somehow seems like an eternity amid this summer’s news cycles. Thankfully, art offers its own distinct time signature. When we look at a painting or read a poem, we don’t escape from time, but we do experience it differently. Time contracts and dilates; it folds in and out; mere sequence becomes pattern, shape, meaning. “You are the music / While the music lasts,” as T. S. Eliot puts it. This temporal re-shuffling is one of the gifts of art, and it’s one that I’m especially appreciating during this frenetic summer. With persistent, fast-moving advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) cornering most of us every day, even the most technology-shy have begun to accept that AI now infiltrates nearly every aspect of our lives. However, while AI may be useful for retrieving data and making predictions, using it for the intimate and challenging endeavor that is therapy is one purpose you likely wouldn’t have seen coming. Yet, increasing numbers of people are sharing how they are using ChatGPT and other AI-led bots for “makeshift therapy”—which has also left experts questioning how safe this new practice is.

With persistent, fast-moving advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) cornering most of us every day, even the most technology-shy have begun to accept that AI now infiltrates nearly every aspect of our lives. However, while AI may be useful for retrieving data and making predictions, using it for the intimate and challenging endeavor that is therapy is one purpose you likely wouldn’t have seen coming. Yet, increasing numbers of people are sharing how they are using ChatGPT and other AI-led bots for “makeshift therapy”—which has also left experts questioning how safe this new practice is. The first time I heard nematode worms can teach us something about human longevity, I balked at the idea. How the hell can a worm with an average lifespan of only 15 days have much in common with a human who lives decades?

The first time I heard nematode worms can teach us something about human longevity, I balked at the idea. How the hell can a worm with an average lifespan of only 15 days have much in common with a human who lives decades?