Steve Nadis in Quanta:

“Neural networks are currently the most powerful tools in artificial intelligence,” said Sebastian Wetzel(opens a new tab), a researcher at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics. “When we scale them up to larger data sets, nothing can compete.”

“Neural networks are currently the most powerful tools in artificial intelligence,” said Sebastian Wetzel(opens a new tab), a researcher at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics. “When we scale them up to larger data sets, nothing can compete.”

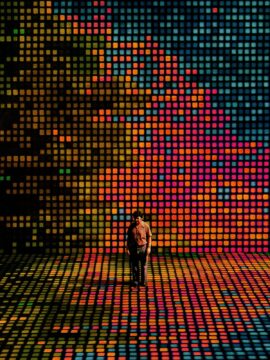

And yet, all this time, neural networks have had a disadvantage. The basic building block of many of today’s successful networks is known as a multilayer perceptron, or MLP. But despite a string of successes, humans just can’t understand how networks built on these MLPs arrive at their conclusions, or whether there may be some underlying principle that explains those results. The amazing feats that neural networks perform, like those of a magician, are kept secret, hidden behind what’s commonly called a black box.

AI researchers have long wondered if it’s possible for a different kind of network to deliver similarly reliable results in a more transparent way.

An April 2024 study(opens a new tab) introduced an alternative neural network design, called a Kolmogorov-Arnold network (KAN), that is more transparent yet can also do almost everything a regular neural network can for a certain class of problems.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Kishore Mahbubani: Western diplomats must first understand how much power has shifted from Europe to Asia. In 1980, the European Union’s GDP was ten times larger than China’s. Today, the two are roughly equal. Goldman Sachs

Kishore Mahbubani: Western diplomats must first understand how much power has shifted from Europe to Asia. In 1980, the European Union’s GDP was ten times larger than China’s. Today, the two are roughly equal. Goldman Sachs  In the 1960s, Arthur C. Clarke was

In the 1960s, Arthur C. Clarke was  W

W Right away, Lee Isaac Chung’s Twisters won me over with a twist I did not expect: it killed off almost its entire cast of young STEM jerks in the first big scene. I’m so sick of these chipper teams of Spielbergian science kids in everything. Read a real book for a change. “Five years later,” they’ve been replaced by an alternative group of gnarly storm-chasing tornado wranglers—older STEM kids in disguise, but a slight improvement.

Right away, Lee Isaac Chung’s Twisters won me over with a twist I did not expect: it killed off almost its entire cast of young STEM jerks in the first big scene. I’m so sick of these chipper teams of Spielbergian science kids in everything. Read a real book for a change. “Five years later,” they’ve been replaced by an alternative group of gnarly storm-chasing tornado wranglers—older STEM kids in disguise, but a slight improvement. I

I T

T Around Christmas Eve 1955,

Around Christmas Eve 1955,  Genetic analysis of a Neanderthal fossil found in France reveals that it was from a previously unknown lineage, a remnant of an ancient population that had remained in extreme isolation for more than 50,000 years. This finding sheds new light on the final phase of the species’ existence.

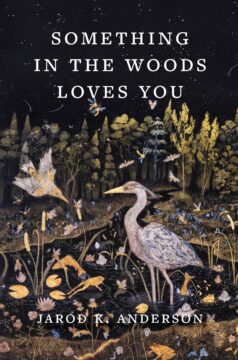

Genetic analysis of a Neanderthal fossil found in France reveals that it was from a previously unknown lineage, a remnant of an ancient population that had remained in extreme isolation for more than 50,000 years. This finding sheds new light on the final phase of the species’ existence. I have difficulty interpreting the nature of my own life, a thing I feel intimately and continuously, so it’s not surprising that we can’t all agree on the nature of herons.

I have difficulty interpreting the nature of my own life, a thing I feel intimately and continuously, so it’s not surprising that we can’t all agree on the nature of herons.