John Adamson at Literary Review:

Ever since Thomas Carlyle first launched his Letters and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell on the world in 1845, the Lord Protector’s published words have exercised an almost mesmeric hold on posterity. Overnight, they transformed a figure who had hitherto been a byword for villainy – was he not the killer of King Charles I? – into a hero for the new Victorian age: a God-fearing, class-transcending champion of ‘russet-coated captains’ who became Britain’s first non-royal head of state. His words resonated with a newly politically ascendant and morally earnest middle class. And in Hamo Thornycroft’s vast sculpture installed outside Westminster Hall in 1899, the Carlylean transformation of Oliver begun by the Letters and Speeches found its embodiment in bronze.

Ever since Thomas Carlyle first launched his Letters and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell on the world in 1845, the Lord Protector’s published words have exercised an almost mesmeric hold on posterity. Overnight, they transformed a figure who had hitherto been a byword for villainy – was he not the killer of King Charles I? – into a hero for the new Victorian age: a God-fearing, class-transcending champion of ‘russet-coated captains’ who became Britain’s first non-royal head of state. His words resonated with a newly politically ascendant and morally earnest middle class. And in Hamo Thornycroft’s vast sculpture installed outside Westminster Hall in 1899, the Carlylean transformation of Oliver begun by the Letters and Speeches found its embodiment in bronze.

Cromwell’s letters and speeches have long beguiled and frustrated the great man’s biographers. Most concur that they hold the key to the inwardness of this most inscrutable and turbulent of souls, even if, so far, that key has never quite turned in the lock. Ever more scholarly editions of his collected writings have followed.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

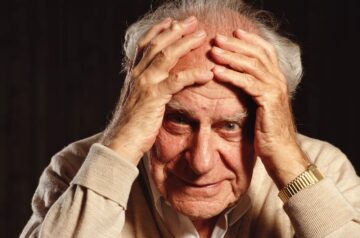

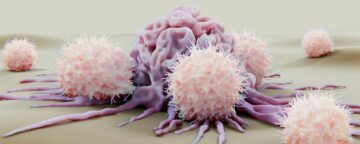

An age ‘clock’ based on some 200 proteins found in the blood can predict a person’s risk of developing 18 chronic illnesses, including

An age ‘clock’ based on some 200 proteins found in the blood can predict a person’s risk of developing 18 chronic illnesses, including

Three times a day my phone pings with a notification telling me that I have a new happiness survey to take. The survey, from

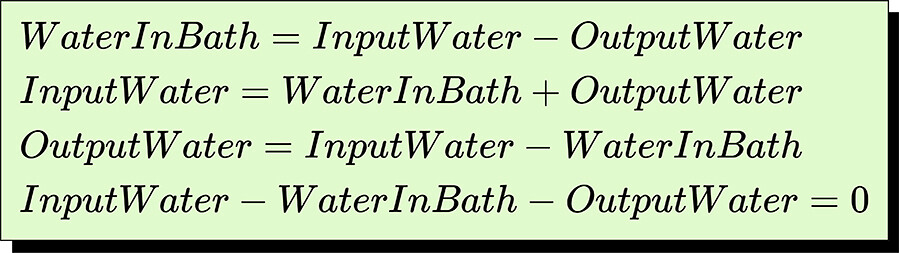

Three times a day my phone pings with a notification telling me that I have a new happiness survey to take. The survey, from  How could gaining knowledge amount to anything other than discovering what was already there? How could the truth of a statement or a theory be anything but its correspondence to facts that were fixed before we started investigating them?

How could gaining knowledge amount to anything other than discovering what was already there? How could the truth of a statement or a theory be anything but its correspondence to facts that were fixed before we started investigating them?

Writers are those naïfs among us who believe that language can be used to take the measure of experience. Readers demonstrate faith in them when they commit to a book or short story. The reader-writer relationship is a contract of sorts. But because the terms are not written down, there is much room in that contract for misinterpretation. What is at stake is not small: it is a shared picture of reality. Nor is it static. With each new publication or rereading, the reader-writer contract is up for review. What could go wrong?

Writers are those naïfs among us who believe that language can be used to take the measure of experience. Readers demonstrate faith in them when they commit to a book or short story. The reader-writer relationship is a contract of sorts. But because the terms are not written down, there is much room in that contract for misinterpretation. What is at stake is not small: it is a shared picture of reality. Nor is it static. With each new publication or rereading, the reader-writer contract is up for review. What could go wrong? W

W I do not think that being mean is a virtue, but it is related to the virtue by means of which we tell the truth. There are other ways of telling the truth. We can be circumspect or ironic—there is very often a nicer way to put something. Yet there are good reasons for sometimes being just a little bit mean. (No, I am not thinking about that gratuitously nasty and rebarbative character now dominating our public realm.) I think of being mean the way that the King of Brobdingnag in Gulliver’s Travels talks about dangerous views: “For a man may be allowed to keep poisons in his closet, but not to vend them about for cordials.” That is to say, I think being nice is required for good politics, but being mean has definite social utility in private life—and it should stay there.

I do not think that being mean is a virtue, but it is related to the virtue by means of which we tell the truth. There are other ways of telling the truth. We can be circumspect or ironic—there is very often a nicer way to put something. Yet there are good reasons for sometimes being just a little bit mean. (No, I am not thinking about that gratuitously nasty and rebarbative character now dominating our public realm.) I think of being mean the way that the King of Brobdingnag in Gulliver’s Travels talks about dangerous views: “For a man may be allowed to keep poisons in his closet, but not to vend them about for cordials.” That is to say, I think being nice is required for good politics, but being mean has definite social utility in private life—and it should stay there. Robotic vehicles can

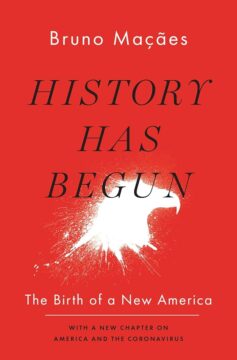

Robotic vehicles can  One of the core assumptions of modern liberalism is that if you can solve the problem of material scarcity, you can go a long way to solving the problem of free and peaceful coexistence among equals. Modern technology has been essential to that dynamic from the start, a key driver of “development” and the success of democratic regimes. The West, and large parts of the rest of the world, are what they are today in great measure due to this project.

One of the core assumptions of modern liberalism is that if you can solve the problem of material scarcity, you can go a long way to solving the problem of free and peaceful coexistence among equals. Modern technology has been essential to that dynamic from the start, a key driver of “development” and the success of democratic regimes. The West, and large parts of the rest of the world, are what they are today in great measure due to this project.