Michael Chorost in the Chronicle of Higher Education:

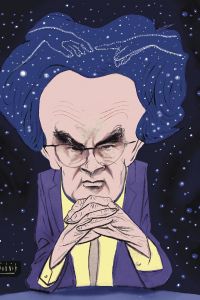

Thomas Nagel is a leading figure in philosophy, now enjoying the title of university professor at New York University, a testament to the scope and influence of his work. His 1974 essay “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” has been read by legions of undergraduates, with its argument that the inner experience of a brain is truly knowable only to that brain. Since then he has published 11 books, on philosophy of mind, ethics, and epistemology.

Thomas Nagel is a leading figure in philosophy, now enjoying the title of university professor at New York University, a testament to the scope and influence of his work. His 1974 essay “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” has been read by legions of undergraduates, with its argument that the inner experience of a brain is truly knowable only to that brain. Since then he has published 11 books, on philosophy of mind, ethics, and epistemology.

But Nagel's academic golden years are less peaceful than he might have wished. His latest book, Mind and Cosmos (Oxford University Press, 2012), has been greeted by a storm of rebuttals, ripostes, and pure snark. “The shoddy reasoning of a once-great thinker,” Steven Pinker tweeted. The Weekly Standard quoted the philosopher Daniel Dennett calling Nagel a member of a “retrograde gang” whose work “isn't worth anything—it's cute and it's clever and it's not worth a damn.”

The critics have focused much of their ire on what Nagel calls “natural teleology,” the hypothesis that the universe has an internal logic that inevitably drives matter from nonliving to living, from simple to complex, from chemistry to consciousness, from instinctual to intellectual.

This internal logic isn't God, Nagel is careful to say. It is not to be found in religion. Still, the critics haven't been mollified. According to orthodox Darwinism, nature has no goals, no direction, no inevitable outcomes. Jerry Coyne, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Chicago, is among those who took umbrage. When I asked him to comment for this article, he wrote, “Nagel is a teleologist, and although not an explicit creationist, his views are pretty much anti-science and not worth highlighting. However, that's The Chronicle's decision: If they want an article on astrology (which is the equivalent of what Nagel is saying), well, fine and good.”

More here.