Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Sunday Poem

Nurture

From a documentary on marsupials I learn

that a pillowcase makes a fine

substitute pouch for an orphaned kangaroo.

I am drawn to such dramas of animal rescues.

They are warm in the throat. I suffer, the critic proclaims,

from an overabundance of female genes.

Bring me your fallen fledgling, your bummer lamb,

lead the abused, the starvelings, into my barn.

Advise the hunted deer to leap into my corn.

And had there been a wild child—

filthy and fierce as a ferret, he is called

in one nineteenth century account—

a wild child to love, it is safe to assume,

given my fireside inked with paw prints,

there would have been room.

Think of the language we two, same and not-same,

might have constructed from sign,

scratch, grimace, grunt, vowel:

Laughter our first noun, and our long verb, howl.

by Maxine Kumin

from Nurture

Viking, 1989

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, October 11, 2024

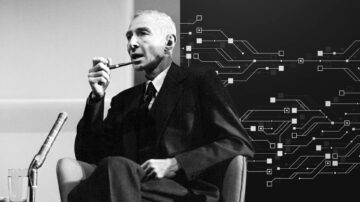

How a Cold War plan to stop nuclear proliferation could protect the world from an AI arms race

Ashutosh Jogalekar and Charles Oppenheimer at Fast Company:

A few days after the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima, Robert Oppenheimer (one of the author’s grandfather) wrote in a letter to his old teacher, Herbert Smith, that “the future, which has so many elements of high promise, is yet only a stone’s throw from despair.” The promise that Oppenheimer was talking about was the promise that the horror of nuclear weapons might abolish war. The despair that he was talking about was the despair that mankind may not be wise enough to handle this millennial source of power without destroying itself.

A few days after the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima, Robert Oppenheimer (one of the author’s grandfather) wrote in a letter to his old teacher, Herbert Smith, that “the future, which has so many elements of high promise, is yet only a stone’s throw from despair.” The promise that Oppenheimer was talking about was the promise that the horror of nuclear weapons might abolish war. The despair that he was talking about was the despair that mankind may not be wise enough to handle this millennial source of power without destroying itself.

In 1946, Under-Secretary of State Dean Acheson asked the Chairman of the Tennessee Valley Authority and soon-to-be Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, David Lilienthal, to compose a report analyzing the threat of nuclear weapons and proposing a plan of action for the United States to present to the newly created United Nations. As scientific and industrial counsel, Lilienthal appointed Oppenheimer and a small team of consultants to advise him and craft the report.

Unofficially led by Oppenheimer as the one with the most knowledge, the committee came up with a proposal that presented the peculiar juxtaposition of being both radical and logical. The Acheson-Lilienthal Report was presented to the president and secretary of state in March 1946.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A critical and unpredictable new phase of the climate crisis

James Dinneen in New Scientist:

A growing number of the planet’s “vital signs” have reached record levels due to climate change and other environmental threats, according to a stark report by a group of prominent researchers.

A growing number of the planet’s “vital signs” have reached record levels due to climate change and other environmental threats, according to a stark report by a group of prominent researchers.

“We are on the brink of an irreversible climate disaster,” write William Ripple at Oregon State University and his colleagues. “This is a global emergency beyond any doubt. Much of the very fabric of life on Earth is imperilled.”

The report is the fifth annual State of the Climate report led by Ripple in an effort to present a clear warning of what the researchers say is a crisis given the extremes measured across key climate indicators, from greenhouse gas levels to tree cover loss.

“The climate crisis isn’t a distant threat, it’s a here-and-now crisis,” says Michael Mann at the University of Pennsylvania, one of several well-known co-authors of the report, which also includes historian Naomi Oreskes, Earth scientist Tim Lenton and oceanographer Stefan Rahmstorf.

The researchers assessed 35 “planetary vital signs”, including the amount of heat in the oceans and the thickness of glaciers.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

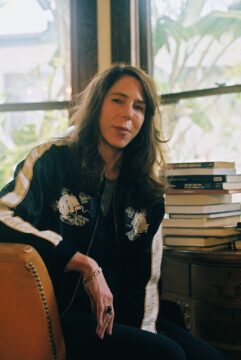

A Smart, Sinuous Espionage Thriller Brimming With Heat

Dwight Garner in the New York Times:

Rachel Kushner’s new novel, “Creation Lake,” is set in rural France, but not the rural France of guidebooks and Peter Mayle memoirs. No one rhapsodizes over an escargot or a tarte Tatin. We’re in the country’s southwest, where the soil is rocky. More essentially, we are in what Kushner calls the proletarian “real Europe,” with vistas of “highways and nuclear power plants” and “windowless distribution warehouses.”

Rachel Kushner’s new novel, “Creation Lake,” is set in rural France, but not the rural France of guidebooks and Peter Mayle memoirs. No one rhapsodizes over an escargot or a tarte Tatin. We’re in the country’s southwest, where the soil is rocky. More essentially, we are in what Kushner calls the proletarian “real Europe,” with vistas of “highways and nuclear power plants” and “windowless distribution warehouses.”

Kushner’s narrator is an American spy-for-hire. She’s 34, a dropout from a Berkeley Ph.D. program in rhetoric. She is working under an assumed name, “Sadie Smith,” that has unnecessary — for this reader — literary undertones. Sadie has come to this region to infiltrate a radical farming commune bent on violence.

More here. And read an excerpt from the book here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

2024 Nobel Laureate David Baker: Protein design using deep learning

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

On The Village Voice

Ed Park at Harper’s Magazine:

I started at the Voice while in grad school in 1994. I was new to the city, in love with it but slightly terrified. I was looking for part-time work, and a friend of a friend put me in touch with the copy chief at the paper. I passed the test, armed with Webster’s 10th and Chicago 14 and a much-thumbed xeroxed packet covering house style. I took a couple shifts a week, usually from 11 am to 7 pm, working in a sunny room on the third floor with the rest of copy and fact-checking—about a dozen people, most days.

I started at the Voice while in grad school in 1994. I was new to the city, in love with it but slightly terrified. I was looking for part-time work, and a friend of a friend put me in touch with the copy chief at the paper. I passed the test, armed with Webster’s 10th and Chicago 14 and a much-thumbed xeroxed packet covering house style. I took a couple shifts a week, usually from 11 am to 7 pm, working in a sunny room on the third floor with the rest of copy and fact-checking—about a dozen people, most days.

We stared at our ATEX monitors, which had the scrapyard aesthetic of Seventies science fiction: amber letters on scuzzy screens, chunky keyboards that crackled like small-arms fire. When a new story hit the queue, we newbies raced to give it a read. I’d swoop in if I saw, say, a piece by the art-house film reviewer J. Hoberman or the gossip columnist Michael Musto or the soi-disant “dean of American rock critics,” Robert Christgau. None of them ever phoned it in. Other names invited hesitation, and the copy chief would prod us over ATEX. Once you entered corrections and queries, you’d type your initials in the “c1” field at the top and return it to the editor, who would process the changes and send it back to the queue for a second read.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Read Your Way Through Seoul

Han Kang at the NYT:

Seoul is a megacity, with a population of nearly 10 million and a name pronounced like “soul.” There were times when I couldn’t stand its scale and pace of change, but I have managed to find a tranquil corner and continue to live in this city. Although modern at first glance, Seoul has a long history. People first began to gather here 6,000 years ago. Over the centuries, the city was the center of dynasties that ruled the region, and it remains the capital of South Korea.

Seoul is a megacity, with a population of nearly 10 million and a name pronounced like “soul.” There were times when I couldn’t stand its scale and pace of change, but I have managed to find a tranquil corner and continue to live in this city. Although modern at first glance, Seoul has a long history. People first began to gather here 6,000 years ago. Over the centuries, the city was the center of dynasties that ruled the region, and it remains the capital of South Korea.

In other words, the city exists under thick layers of time. News of construction projects brought to a stop after digging in the city center unearthed drainage facilities from a thousand years ago or porcelain dating back hundreds of years is a reminder of that. As I walk past the stone markers of old buildings destroyed during the Japanese occupation, from 1910 to 1945, or a brutal ideological war, from 1950 to 1953, I see the royal palaces and traditional private houses that have survived, the apartment complexes built since the 1960s that have evolved into high-rises, the commercial skyscrapers dazzling with night lights.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Is Malcolm Gladwell Out of Ideas?

Anand Giridharadas in The New York Times:

Malcolm Gladwell could have written a fresh book. Instead, he created a brand extension of his 2000 hit, “The Tipping Point.” The result, “Revenge of the Tipping Point,” is a genre bender: self-help without the practical advice, storytelling without the literariness, nonfiction without the vital truths, entertainment without the pleasure, a thriller without actual revelation and a business book without the actionable insights.

Malcolm Gladwell could have written a fresh book. Instead, he created a brand extension of his 2000 hit, “The Tipping Point.” The result, “Revenge of the Tipping Point,” is a genre bender: self-help without the practical advice, storytelling without the literariness, nonfiction without the vital truths, entertainment without the pleasure, a thriller without actual revelation and a business book without the actionable insights.

But it will be big! For Gladwell’s books belong to that special category where books are not books so much as advertisements. “Revenge of the Tipping Point” might get you to sign up for Gladwell’s MasterClass course on storytelling. It might lead you to Pushkin Industries, the podcast company he helped start. Or it could inspire a business to hire him to give the new talk his speaking agency is already marketing on “how not to miss the forest for the trees.” My criticism isn’t that Gladwell speaks to a wide audience. That is what I admire most about him. He is the literary equivalent of those politicians who get nonvoters to the polls. With legacy media eroding and book sales sluggish and disinformation spreading and truth under attack by some of our own leaders, millions of people live in idea deserts. For them, Gladwell is a farm stand.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Scientists Say Net Zero Aviation Is Possible by 2050—If We Act Now

Ed Gent in Singularity Hub:

Aviation has proven to be one of the most stubbornly difficult industries to decarbonize. But a new roadmap outlined by University of Cambridge researchers says the sector could reach net zero by 2050 if urgent action is taken. The biggest challenge when it comes to finding alternatives to fossil fuels in aviation is basic physics. Jet fuel is incredibly energy dense, which is crucial for a mode of transport where weight savings can dramatically impact range. While efforts are underway to build planes powered by batteries, hydrogen, or methane, none can come close to matching kerosene, pound for pound, at present. Sustainable aviation fuel is another option, but so far, its uptake has been limited, and its green credentials are debatable.

Aviation has proven to be one of the most stubbornly difficult industries to decarbonize. But a new roadmap outlined by University of Cambridge researchers says the sector could reach net zero by 2050 if urgent action is taken. The biggest challenge when it comes to finding alternatives to fossil fuels in aviation is basic physics. Jet fuel is incredibly energy dense, which is crucial for a mode of transport where weight savings can dramatically impact range. While efforts are underway to build planes powered by batteries, hydrogen, or methane, none can come close to matching kerosene, pound for pound, at present. Sustainable aviation fuel is another option, but so far, its uptake has been limited, and its green credentials are debatable.

Despite this, the authors of a new report from the University of Cambridge’s Aviation Impact Accelerator (AIA) say that with a concerted effort the industry can clean up its act. The report outlines four key sustainable aviation goals that, if implemented within the next five years, could help the sector become carbon neutral by the middle of the century. “Too often the discussions about how to achieve sustainable aviation lurch between overly optimistic thinking about current industry efforts and doom-laden cataloging of the sector’s environmental evils,” Eliot Whittington, executive director at the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership, said in a press release.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Edward Said & Salman Rushdie

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday, October 10, 2024

Is the United States a prisoner of its own mythology?

Tom Zoellner in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

The stories that a country tells itself are just as critical to its functioning as its army, its laws, its borders, and its flag. Where did the country emerge from, and where might it be heading?

The stories that a country tells itself are just as critical to its functioning as its army, its laws, its borders, and its flag. Where did the country emerge from, and where might it be heading?

Such questions of national mythology are especially fraught in the United States, still relatively young in the world, big, rich, powerful, multiethnic, and operating on a set of profoundly contradictory ideas. That it might be possible to make sense of American political division by naming those myths and interpreting the news of the day through their filter is the guiding ambition of Richard Slotkin’s exciting and detailed new decoder ring of a book, A Great Disorder: National Myth and the Battle for America.

The title is an homage to the Wallace Stevens poem “Connoisseur of Chaos,” which declares that “a great disorder is an order”—not just as a metaphysical statement but also as a tidy description of the contested historiography of the United States. Can we look into our past to find the white, Christian, hierarchical, free-market society of red America’s imagining? Or do we see the imperfect but ever-striving egalitarian and multiethnic vision of blue America? Both sides have told selective stories, which are neither completely true nor exactly false.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How ideas from physics drive AI: the 2024 Nobel Prize

Ethan Siegel at Big Think:

When most of us think of AI, we think of chatbots like ChatGPT, of image generators like DALL-E, or of scientific applications like AlphaFold for predicting protein folding structures. Very few of us, however, think about physics as being at the core of artificial intelligence systems. But the notion of an artificial neural network indeed came to fruition first as the result of physics studies across three disciplines — biophysics, statistical physics, and computational physics — all fused together. It’s because of this seminal work, undertaken largely in the 1980s, that the widespread uses of artificial intelligence and machine learning that permeate more and more of daily life are available to us today.

When most of us think of AI, we think of chatbots like ChatGPT, of image generators like DALL-E, or of scientific applications like AlphaFold for predicting protein folding structures. Very few of us, however, think about physics as being at the core of artificial intelligence systems. But the notion of an artificial neural network indeed came to fruition first as the result of physics studies across three disciplines — biophysics, statistical physics, and computational physics — all fused together. It’s because of this seminal work, undertaken largely in the 1980s, that the widespread uses of artificial intelligence and machine learning that permeate more and more of daily life are available to us today.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

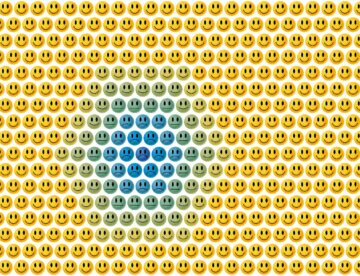

The Real (Weird) Way We See Numbers

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How can poor countries become rich?

Karthik Tadepalli in Asterisk:

To many people, “development economics” is synonymous with the randomized controlled trial: randomly assigning some group of people to an intervention, like cash transfers or malaria protection nets, in order to tell if it really makes the recipients better off. RCTs have revolutionized development economics and international aid policy. The RCT pioneers Esther Duflo, Abhijit Banerjee, and Michael Kremer won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2019, and the chief economist of USAID, Dean Karlan, is a prominent RCT advocate. RCTs are influential because they are a powerful tool to cut through uncertainty and preconceptions. For example, international development practitioners long believed that providing textbooks in underfunded schools would help students learn more: but an RCT in Kenya showed that most students did not benefit from getting textbooks, primarily because they were already learning very little in school. RCTs can help us identify what works. Yet nearly everyone who thinks about development has, at some point, had a crisis of faith.

Skeptics argue that RCTs distort the focus of policymakers toward technocratic questions that lend themselves to studies of limited scope, and away from the hard problems that are ultimately more important. After all, aren’t RCT-driven solutions just Band-Aids over the fundamental reality that poor countries are poor? Shouldn’t we spend our time and money focusing on how to bring economic growth and prosperity to countries, rather than tinkering with partial solutions for a tiny number of people?

This argument is appealing, but it faces difficulties when the rubber meets the road. What would it look like to adopt a “growth strategy” for doing good?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The K-Pop King

Alex Barasch at The New Yorker:

Bang is portly and good-humored. He was born in Seoul and was a solitary, bookish child until his parents, concerned about his shyness, encouraged him to take up the guitar as a hobby. “I went a little bit further than my parents intended,” he said, wryly. He memorized the Billboard charts, got into Led Zeppelin and heavy metal, and formed a band, sometimes skipping classes to jam. He set music aside to secure entrance to Seoul National University, but he soon returned to the scene as a producer. Bang held off on telling his parents until he’d become successful enough to give them an envelope full of cash. “Musicians can make money, too,” he said.

Three decades later, Bang is a billionaire. We spoke through a translator, whom he sometimes outpaced with references to such stars as Kendrick Lamar and Joey Bada$$; often, he became so animated that he switched to English. Bang got his start at JYP Entertainment, a Korean label. In 2005, he formed his own, calling it Big Hit Entertainment.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Jonathan Carroll’s Impossible Realism

Gary K. Wolfe at the LARB:

JONATHAN CARROLL’S The Crow’s Dinner, a 2017 collection of anecdotes, vignettes, and short essays (now republished in ebook form by JABberwocky Literary Agency, along with five other Carroll titles), offers a delightful and generous sampling of the American author’s thoughts about life, art, and living in his adopted hometown of Vienna, but it might seem a bit sparse when it comes to clues about the enigmas of his unique brand of fiction. There are some notable exceptions, though: one is a short piece titled “Impossible Realism,” a term he tells us “may sound like oxymoron” but “makes a great deal of sense when we permit ourselves to look beyond the quotidian and once again open up fully to wonder, like we used to as children.”

JONATHAN CARROLL’S The Crow’s Dinner, a 2017 collection of anecdotes, vignettes, and short essays (now republished in ebook form by JABberwocky Literary Agency, along with five other Carroll titles), offers a delightful and generous sampling of the American author’s thoughts about life, art, and living in his adopted hometown of Vienna, but it might seem a bit sparse when it comes to clues about the enigmas of his unique brand of fiction. There are some notable exceptions, though: one is a short piece titled “Impossible Realism,” a term he tells us “may sound like oxymoron” but “makes a great deal of sense when we permit ourselves to look beyond the quotidian and once again open up fully to wonder, like we used to as children.”

As a literary descriptor, “impossible realism” avoids the considerable baggage attached to “magic realism”—which has often been invoked to describe Carroll—as well as the more genre-oriented boxes of fantasy and horror, which Carroll has justifiably complained about, despite having won both the World Fantasy Award and the Bram Stoker Award (probably the most prestigious award for horror fiction).

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Picture imperfect

Charles Piller in Science:

In 2016, when the U.S. Congress unleashed a flood of new funding for Alzheimer’s disease research, the National Institute on Aging (NIA) tapped veteran brain researcher Eliezer Masliah as a key leader for the effort. He took the helm at the agency’s Division of Neuroscience, whose budget—$2.6 billion in the last fiscal year—dwarfs the rest of NIA combined. As a leading federal ambassador to the research community and a chief adviser to NIA Director Richard Hodes, Masliah would gain tremendous influence over the study and treatment of neurological conditions in the United States and beyond. He saw the appointment as his career capstone. Masliah told the online discussion site Alzforum that “the golden era of Alzheimer’s research” was coming and he was eager to help NIA direct its bounty. “I am fully committed to this effort. It is a historical moment.”

In 2016, when the U.S. Congress unleashed a flood of new funding for Alzheimer’s disease research, the National Institute on Aging (NIA) tapped veteran brain researcher Eliezer Masliah as a key leader for the effort. He took the helm at the agency’s Division of Neuroscience, whose budget—$2.6 billion in the last fiscal year—dwarfs the rest of NIA combined. As a leading federal ambassador to the research community and a chief adviser to NIA Director Richard Hodes, Masliah would gain tremendous influence over the study and treatment of neurological conditions in the United States and beyond. He saw the appointment as his career capstone. Masliah told the online discussion site Alzforum that “the golden era of Alzheimer’s research” was coming and he was eager to help NIA direct its bounty. “I am fully committed to this effort. It is a historical moment.”

Masliah appeared an ideal selection. The physician and neuropathologist conducted research at the University of California San Diego (UCSD) for decades, and his drive, curiosity, and productivity propelled him into the top ranks of scholars on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. His roughly 800 research papers, many on how those conditions damage synapses, the junctions between neurons, have made him one of the most cited scientists in his field. His work on topics including alpha-synuclein—a protein linked to both diseases—continues to influence basic and clinical science.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday Poem

Buddha

I used to sit under trees and meditate

on the diamond bright silence of darkness

and the bright look of diamonds in space

and space that was stiff with lights

and diamonds shot through, and silence

And when a dog barked I took it for soundwaves

and cars passing too, and once I heard

a jet plane which I thought was a mosquito

in my heart, and once I saw salmon walls

of pink and roses, moving and ululating

with the drapish

Once I forgave dogs, and pitied men, sat

in the rain countin Juju beads, raindrops

are ecstacy, ecstacy is raindrops—birds

sleep when the trees are giving out light

in the night, when rabbits sleep too, and dogs

I had a path that I followed through piney woods

and a phosphorescent white hound-dog named Bob

who led me the way when the clouds covered

the stars, and then communicated to me

the sleepings of a loving dog enamoured

of God.

On Saturday mornings I was there, in the sun,

contemplating the blue-bright air, as eyes

of Lone Ranger penetrated the dust

of my canyon thoughts, and Indians

and children, and movie shows

Or Saturday morning in China when all is so fair

crystal imaginings of pristine lakes, talk

with rocks, walks with Chi-pack across

Mongolias and silent temple rocks in valleys

of boulder and tarn-washed clay,—shh—

sit and otay

and if men were dyin or sleepin in rooftops

beyond, or frogs croaked once or thrice

to indicate supreme mystical majesty, what’s

the diff? and I saw blue sky no different

from dead cat—and love and marriage

No different than mud—that’s blood—

and lighted clay too—illuminated intelligence

faces of angels everywhere, with Dostoyevsky’s

unease praying in their X-brow faces,

twisted and great,

And many a time the Buddha played a leaf

on me at midnight thinkin-time, to

remind me “This Thinking Has Stopped,’

which it had, because no thinking was there

but wasnt liquidly mysteriously brainly there

And finally I turned into a diamond stone

and sat rigid and golden, gold too—didn’t dare

breathe, to break up the diamond that cant

even cut into butter anyway, how brittle

the diamond, how quick returned thought—

impossible to exist

………… Buddha say:

………… ‘All’s possible’

by Jack Kerouac

from Poems All Sizes

City Light Books San Francisco, 1992

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Robert Downey Jr. Is a Novelist With a Novel Muse in ‘McNeal’

Jesse Green in The New York Times:

Certainly Jacob McNeal, played by the formidable Robert Downey Jr., is more a data set than a character. A manly, hard-driving literary novelist of the old school, like Saul Bellow or Philip Roth, he is not at all the magnetic and personable man Akhtar describes in the script; rather, he is whiny, entitled and fatuous. (“At my simple best, I’m a poet,” he says.) About the only time he engages instead of repels is when, in the amusing opening scene, as his doctor (Ruthie Ann Miles) prepares to deliver bad news, he fails to get ChatGPT to tell him his chances of winning the Nobel Prize.

Certainly Jacob McNeal, played by the formidable Robert Downey Jr., is more a data set than a character. A manly, hard-driving literary novelist of the old school, like Saul Bellow or Philip Roth, he is not at all the magnetic and personable man Akhtar describes in the script; rather, he is whiny, entitled and fatuous. (“At my simple best, I’m a poet,” he says.) About the only time he engages instead of repels is when, in the amusing opening scene, as his doctor (Ruthie Ann Miles) prepares to deliver bad news, he fails to get ChatGPT to tell him his chances of winning the Nobel Prize.

“I hope this was helpful,” the bot types.

“It was not, you soulless, silicon suck-up,” he replies.

We are meant to understand that McNeal is a man who wears his awfulness, in this case his vanity, as an adorable idiosyncrasy, as if it were a feathered hat. He flirts and philanders with equal obliviousness to moral implications. He aggressively asserts his anti-woke bona fides. While being interviewed by a New York Times journalist, who is Black, he asks if she was a “diversity hire.” And when she fails to take the bait, he adds, as a man of his sophistication would know enough not to, “Did I say something wrong?”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.