Aaron Bady in Boston Review:

My grandmother was a good Catholic who didn’t go to college and had eight children. Her oldest child went to college and had one child, me. Your own family probably fits this pattern. In a decline that correlates with education and secularism, and is concentrated in the Global North, women across the world are having about half the number of children they had only fifty years ago.

The far right sees this choice as a specific kind of crisis. While anti-abortion, anti-immigrant nationalists like J. D. Vance might not use exactly fourteen words when they rail against “childless cat ladies,” they echo eugenicists like Madison Grant and Theodore Roosevelt in blaming female emancipation for “race suicide.” America was “great” when (white) families were large because (white) women were in the home having children, and (white) labor was cheap enough to make large-scale (nonwhite) immigration unnecessary. It does not mitigate the problem that about half of the current rate of population increase in the United States comes from new immigration; for them, that is the problem.

The liberal counternarrative tends to be a smaller story, about individuals choosing not to be parents. More people are making this choice, they concede, but the important question is whether people are choosing freely. Are those who never wanted children—especially women historically forced into childbearing—finally free to forgo them? Or are those who would want children choosing not to have them, for economic or cultural reasons, or out of anxiety about a war-ridden, warming world?

However strange it may sound to characterize the post-Roe present as overflowing with reproductive choice, the mainstream center-left tends to agree with the far right that this choice is a new phenomenon, and that our predecessors were spared the existential dilemma.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A

A “Mr. Handel’s head is more full of Maggots than ever. … I could tell you more … but it grows late & I must defer the rest until I write next; by which time, I doubt not, more new ones will breed in his Brain.”

“Mr. Handel’s head is more full of Maggots than ever. … I could tell you more … but it grows late & I must defer the rest until I write next; by which time, I doubt not, more new ones will breed in his Brain.” There were, of course, other ways to feel connected with humanity on a plane. You could notice a slight indentation left in the seat from the person before you, or the length to which they had extended (or shortened) their seatbelt, which would now become yours. You didn’t have to turn to the back of the in-flight magazine to see some stranger’s—or, more likely, strangers’—handiwork on the crossword, or wonder what flavor of sticky substance someone had spilled across its pages. Nor was it required to retrace the doodles drawn on the ads for UNTUCKit shirts, It’s Just Lunch, Hard Rock Café, Wellendorff jewelry, companies selling gold coins, and Big Green Eggs. But it’s clear that with the last print issue of Hemispheres, the in-flight magazine of United Airlines, and the last such magazine connected to a major US carrier (with the exception of Hana Hou!, for Hawaiian Airlines), it is the end of an era.

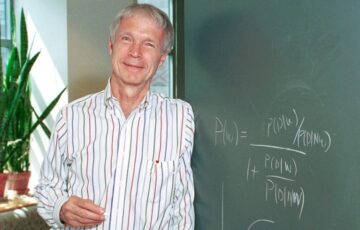

There were, of course, other ways to feel connected with humanity on a plane. You could notice a slight indentation left in the seat from the person before you, or the length to which they had extended (or shortened) their seatbelt, which would now become yours. You didn’t have to turn to the back of the in-flight magazine to see some stranger’s—or, more likely, strangers’—handiwork on the crossword, or wonder what flavor of sticky substance someone had spilled across its pages. Nor was it required to retrace the doodles drawn on the ads for UNTUCKit shirts, It’s Just Lunch, Hard Rock Café, Wellendorff jewelry, companies selling gold coins, and Big Green Eggs. But it’s clear that with the last print issue of Hemispheres, the in-flight magazine of United Airlines, and the last such magazine connected to a major US carrier (with the exception of Hana Hou!, for Hawaiian Airlines), it is the end of an era. John Hopfield, one of this year’s

John Hopfield, one of this year’s  The publication of new interviews with Donald Trump’s longstanding chief of staff John Kelly have been in the news since last week, and the Harris campaign has picked up on Kelly’s use of the word “fascist” to describe his former boss. This has reignited a longstanding debate over whether Trump and his MAGA movement represent the threat of genuine fascism in the United States were he to be re-elected.

The publication of new interviews with Donald Trump’s longstanding chief of staff John Kelly have been in the news since last week, and the Harris campaign has picked up on Kelly’s use of the word “fascist” to describe his former boss. This has reignited a longstanding debate over whether Trump and his MAGA movement represent the threat of genuine fascism in the United States were he to be re-elected. In the brief introduction to

In the brief introduction to  Capitalism thwarts and stunts the creativity of human beings. It robs the mass of the population of control over their own labour, and therefore over production generally. It denies the vast majority of people creative expression in their daily work lives, and this affects all of life. Workers are robbed not just of artistic creativity but even of our potential to be an audience for art. Yet there is a constant struggle to free humanity’s potential. And there have always been troublesome artists and troublesome art. The contradictions of capitalism mean that it is possible, at least to some extent, for artistic expression to develop in opposition to the dominant trajectory of society. Bertolt Brecht’s poem “Motto” makes the point:

Capitalism thwarts and stunts the creativity of human beings. It robs the mass of the population of control over their own labour, and therefore over production generally. It denies the vast majority of people creative expression in their daily work lives, and this affects all of life. Workers are robbed not just of artistic creativity but even of our potential to be an audience for art. Yet there is a constant struggle to free humanity’s potential. And there have always been troublesome artists and troublesome art. The contradictions of capitalism mean that it is possible, at least to some extent, for artistic expression to develop in opposition to the dominant trajectory of society. Bertolt Brecht’s poem “Motto” makes the point: L

L New image-making technologies

New image-making technologies If last month’s announcement by Microsoft and Constellation Energy that they planned to restart Three Mile Island was a potent symbol of nuclear energy’s changing fortunes and importance to efforts to decarbonize the US electricity system, this month’s announcements by

If last month’s announcement by Microsoft and Constellation Energy that they planned to restart Three Mile Island was a potent symbol of nuclear energy’s changing fortunes and importance to efforts to decarbonize the US electricity system, this month’s announcements by  Trump is symptom, not cause, of the “crisis of democracy.” Trump did not turn the nation in a hard-right direction, and if the liberal political establishment doesn’t ask what wind he caught in his sails, it will remain clueless about the wellsprings and fuel of contemporary antidemocratic thinking and practices. It will ignore the cratered prospects and anxiety of the working and middle classes wrought by neoliberalism and financialization; the unconscionable alignment of the Democratic Party with those forces for decades; a scandalously unaccountable and largely bought mainstream media and the challenges of siloed social media; neoliberalism’s direct and indirect assault on democratic principles and practices; degraded and denigrated public education; and mounting anxiety about constitutional democracy’s seeming inability to meet the greatest challenges of our time, especially but not only the climate catastrophe and the devastating global deformations and inequalities emanating from two centuries of Euro-Atlantic empire. Without facing these things, we will not develop democratic prospects for the coming century.

Trump is symptom, not cause, of the “crisis of democracy.” Trump did not turn the nation in a hard-right direction, and if the liberal political establishment doesn’t ask what wind he caught in his sails, it will remain clueless about the wellsprings and fuel of contemporary antidemocratic thinking and practices. It will ignore the cratered prospects and anxiety of the working and middle classes wrought by neoliberalism and financialization; the unconscionable alignment of the Democratic Party with those forces for decades; a scandalously unaccountable and largely bought mainstream media and the challenges of siloed social media; neoliberalism’s direct and indirect assault on democratic principles and practices; degraded and denigrated public education; and mounting anxiety about constitutional democracy’s seeming inability to meet the greatest challenges of our time, especially but not only the climate catastrophe and the devastating global deformations and inequalities emanating from two centuries of Euro-Atlantic empire. Without facing these things, we will not develop democratic prospects for the coming century.