Steve Waldman over at his website (image from wikimedia commons):

We are in a depression, but not because we don’t know how to remedy the problem. We are in a depression because it is our revealed preference, as a polity, not to remedy the problem. We are choosing continued depression because we prefer it to the alternatives.

Usually, economists are admirably catholic about the preferences of the objects they study. They infer desire by observing behavior, listening to what people do more than to what they say. But with respect to national polities, macroeconomists presume the existence of an overwhelming preference for GDP growth and full employment that simply does not exist. They act as though any other set of preferences would be unreasonable, unthinkable.

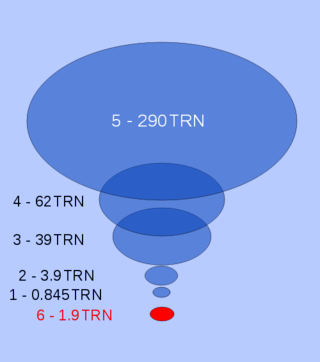

But the preferences of developed, aging polities — first Japan, now the United States and Europe — are obvious to a dispassionate observer. Their overwhelming priority is to protect the purchasing power of incumbent creditors. That’s it. That’s everything. All other considerations are secondary. These preferences are reflected in what the polities do, how they behave. They swoop in with incredible speed and force to bail out the financial sectors in which creditors are invested, trampling over prior norms and laws as necessary. The same preferences are reflected in what the polities omit to do. They do not pursue monetary policy with sufficient force to ensure expenditure growth even at risk of inflation. They do not purse fiscal policy with sufficient force to ensure employment even at risk of inflation. They remain forever vigilant that neither monetary ease nor fiscal profligacy engender inflation. The tepid policy experiments that are occasionally embarked upon they sabotage at the very first hint of inflation. The purchasing power of holders of nominal debt must not be put at risk. That is the overriding preference, in context of which observed behavior is rational.

I am often told that this is absurd because, after all, wouldn’t creditors be better off in a booming economy than in a depressed one? In a depression, creditors may not face unexpected inflation, sure. But they also earn next to nothing on their money, sometimes even a bit less than nothing in real terms. “Financial repression! Savers are being squeezed!” In a boom, they would enjoy positive interest rates.

That’s true. But the revealed preference of the polity is not balanced. It is not some cartoonish capitalist-class conspiracy story, where the goal is to maximize the wealth of exploiters. The revealed preference of the polity is to resist losses for incumbent creditors much more than it is to seek gains. In a world of perfect certainty, given a choice between recession and boom, the polity would choose boom. But in the real world, the polity faces great uncertainty.

More here.