Joel Suarez in n + 1:

“The US economy is currently near perfect.” So wrote the economist Jennifer Harris—“the quiet intellectual force behind the Biden administration’s economic policies,” according to the New York Times—in a tweet posted in mid-July. The tweet has since been deleted, but Harris’s view was hardly idiosyncratic at the time. In the months before Trump’s victory, not just elected Democrats but countless wonks and columnists were celebrating the Biden Administration’s macroeconomic successes: sustained low unemployment, strong GDP growth, falling inflation, and rising wages. This is the stuff of economists’ dreams—and as close to fulfilling labor’s long-held hope of full employment as the country has come in nearly half a century. Under contemporary US capitalism, this is about as good as it gets.

Around the same time that Harris was celebrating the economy, a heated exchange broke out in Congress. Ann Wagner, a Republican representative from Missouri, berated Secretary of State Antony Blinken for the delayed sales of weapons to Israel that “just happen to be made in the St. Louis metropolitan area, in St. Charles, in my district.” She scolded Blinken: “My constituents . . . rely on these jobs to pay for their mortgages, their car payments, their day care costs and they can’t afford to lose their jobs to support this partisan stall tactic.” In response, Blinken seemed flustered but, for once, honest enough: He insisted that there were no intentional delays; Israel would be armed, as it wished; St. Charles would have jobs, as it should; Palestinians would die, as they seemingly must. This encounter prompts a question: how could the economy be “near perfect” if US military largesse was the only thing saving an entire congressional district from immiseration?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Like a pre-teen prodigy performing for grown-ups, Wallace is too show-offy, intent on dazzling us. Thomas Pynchon’s prose has this same adolescent “Look at me!” quality, which is why I could never get through Gravity’s Rainbow. Wallace also reminds me of J.D. Salinger, who sneerily divides characters into the cool, who get it, and the uncool, who don’t.

Like a pre-teen prodigy performing for grown-ups, Wallace is too show-offy, intent on dazzling us. Thomas Pynchon’s prose has this same adolescent “Look at me!” quality, which is why I could never get through Gravity’s Rainbow. Wallace also reminds me of J.D. Salinger, who sneerily divides characters into the cool, who get it, and the uncool, who don’t. W

W S

S Erbai, the outsider, approached the other robots by asking them, “Are you working overtime?”

Erbai, the outsider, approached the other robots by asking them, “Are you working overtime?” Twice during a 90-minute interview about her memoir, Cher asked, “Do you think people are going to like it?”

Twice during a 90-minute interview about her memoir, Cher asked, “Do you think people are going to like it?” Kaput is about the problems facing Germany rather than the successes of the UK. Münchau (the clue is in the umlaut) is very pessimistic about his native land. It can do little right, in his view. In the German version of Winnie-the-Pooh, Pu der Bär, he is I-Aah, the gloomy donkey. But I-Aah often has a good point to make, and so does Münchau.

Kaput is about the problems facing Germany rather than the successes of the UK. Münchau (the clue is in the umlaut) is very pessimistic about his native land. It can do little right, in his view. In the German version of Winnie-the-Pooh, Pu der Bär, he is I-Aah, the gloomy donkey. But I-Aah often has a good point to make, and so does Münchau. Thirty years ago, when Thomas Brinthaupt became a new parent—and was in the thick of long, sleep-deprived days and nights—he started coping by talking out loud to himself. That inspired him to research why people engage in this type of self-talk. A few key reasons have emerged, including social isolation: As you might expect, people who spend lots of time alone

Thirty years ago, when Thomas Brinthaupt became a new parent—and was in the thick of long, sleep-deprived days and nights—he started coping by talking out loud to himself. That inspired him to research why people engage in this type of self-talk. A few key reasons have emerged, including social isolation: As you might expect, people who spend lots of time alone  Researchers are flocking to the social-media platform Bluesky, hoping to recreate the good old days of Twitter.

Researchers are flocking to the social-media platform Bluesky, hoping to recreate the good old days of Twitter. Can a book change a landscape? If ever a book did, it was The Great Gatsby. And if The Great Gatsby did, it did so thanks to one of its first and most ambitious readers, the urban planner Robert Moses.

Can a book change a landscape? If ever a book did, it was The Great Gatsby. And if The Great Gatsby did, it did so thanks to one of its first and most ambitious readers, the urban planner Robert Moses. The generalized efficient markets (GEM) principle says, roughly, that things which would give you a big windfall of money and/or status, will not be easy. If such an opportunity were available, someone else would have already taken it. You will never find a $100 bill on the floor of Grand Central Station at rush hour, because someone would have picked it up already.

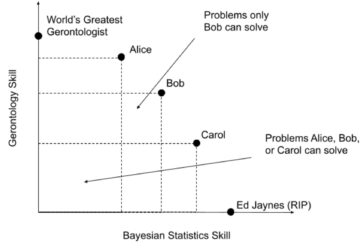

The generalized efficient markets (GEM) principle says, roughly, that things which would give you a big windfall of money and/or status, will not be easy. If such an opportunity were available, someone else would have already taken it. You will never find a $100 bill on the floor of Grand Central Station at rush hour, because someone would have picked it up already.