John Marsh at Literary Hub:

Can a book change a landscape? If ever a book did, it was The Great Gatsby. And if The Great Gatsby did, it did so thanks to one of its first and most ambitious readers, the urban planner Robert Moses.

Can a book change a landscape? If ever a book did, it was The Great Gatsby. And if The Great Gatsby did, it did so thanks to one of its first and most ambitious readers, the urban planner Robert Moses.

Next year marks the one hundredth anniversary of The Great Gatsby. The novel survives in cultural memory as a narrative of star-crossed lovers (Gatsby and Daisy); as a reckoning with the elusive quality of the American dream (Gatsby and the green light); or, most commonly—witness its latest revival on Broadway—as a celebration of the excitement and excess of Jazz Age America. Few remember it for what it is: an indictment of, if not the wealthy per se, than of how wealth can deform basic human decency.

The climax of the novel makes the point. In a Manhattan hotel room, Daisy informs her husband, Tom Buchanan, that she intends to leave him and marry Gatsby. After revealing the sordid ways Gatsby has made his money—bootlegging whiskey and passing fraudulent bonds—Tom bullies Daisy into staying with him.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

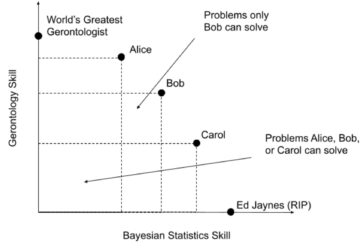

The generalized efficient markets (GEM) principle says, roughly, that things which would give you a big windfall of money and/or status, will not be easy. If such an opportunity were available, someone else would have already taken it. You will never find a $100 bill on the floor of Grand Central Station at rush hour, because someone would have picked it up already.

The generalized efficient markets (GEM) principle says, roughly, that things which would give you a big windfall of money and/or status, will not be easy. If such an opportunity were available, someone else would have already taken it. You will never find a $100 bill on the floor of Grand Central Station at rush hour, because someone would have picked it up already. When Scientific American was bad under Helmuth, it was really bad. For example, did you know that “

When Scientific American was bad under Helmuth, it was really bad. For example, did you know that “

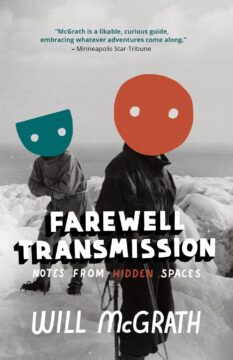

No quote from antiquity sums up the metaphysical challenge of being a surfer more aptly than this one, from Marcus Aurelius, the last Emperor of the Pax Romana: “There is a river of creation, and time is a violent stream. As soon as one thing comes into sight, it is swept past and another is carried down: it too will be taken on its way.” Waves, by their nature, do not hold still. “Catching” one, therefore, can be a kind of thought experiment, a quantum paradox. To hitch yourself onto a surge of liquid energy—to soar across its frothing surface—demands both physical and mental suspension of disbelief.

No quote from antiquity sums up the metaphysical challenge of being a surfer more aptly than this one, from Marcus Aurelius, the last Emperor of the Pax Romana: “There is a river of creation, and time is a violent stream. As soon as one thing comes into sight, it is swept past and another is carried down: it too will be taken on its way.” Waves, by their nature, do not hold still. “Catching” one, therefore, can be a kind of thought experiment, a quantum paradox. To hitch yourself onto a surge of liquid energy—to soar across its frothing surface—demands both physical and mental suspension of disbelief. A

A A

A

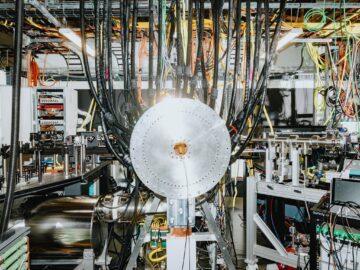

Big-name investors including Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Vinod Khosla and Sam Altman have staked hundreds of millions of dollars on this, fusion’s potential

Big-name investors including Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Vinod Khosla and Sam Altman have staked hundreds of millions of dollars on this, fusion’s potential  I

I

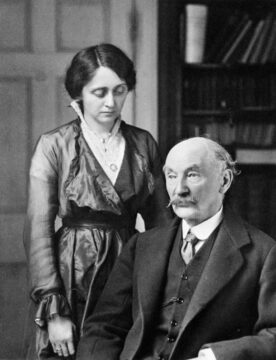

The Monty Python sketch of Thomas Hardy writing “The Return of the Native” takes place inside a packed soccer stadium with an announcer providing play-by-play analysis of the author’s glacial writing process. In hushed tones, the announcer says that Hardy has started to write, but wait, “oh no, it’s a doodle … a piece of meaningless scribble.” At last, Hardy writes “the,” but then crosses it out. In the time it takes to play an entire soccer match, he barely produces a sentence. In fact, Hardy was a speedy writer. He created “The Mayor of Casterbridge” so quickly that if he were outside, he “would scribble on large dead leaves or pieces of stone or slate that came to hand,” Paula Byrne writes in a new biography, “

The Monty Python sketch of Thomas Hardy writing “The Return of the Native” takes place inside a packed soccer stadium with an announcer providing play-by-play analysis of the author’s glacial writing process. In hushed tones, the announcer says that Hardy has started to write, but wait, “oh no, it’s a doodle … a piece of meaningless scribble.” At last, Hardy writes “the,” but then crosses it out. In the time it takes to play an entire soccer match, he barely produces a sentence. In fact, Hardy was a speedy writer. He created “The Mayor of Casterbridge” so quickly that if he were outside, he “would scribble on large dead leaves or pieces of stone or slate that came to hand,” Paula Byrne writes in a new biography, “ C

C McNeal, the new play by Ayad Akhtar, who won the Pulitzer Prize for Disgraced, focuses on an egocentric, self-destructive white male novelist, played by Robert Downey, Jr. The fictional Jacob McNeal—think Mailer or Roth at their worst—wins the Nobel Prize early in the play, but he’s guarding a secret: his latest novel was composed with an uncredited coauthor, an AI chatbot. The production, which considers the controversial notion that artificial intelligence might be a useful creative tool, closes on November 24 after a nearly sold-out run at Lincoln Center. Despite a largely negative critical reception, the show has touched a nerve, which in my view is one of the jobs of a serious writer.

McNeal, the new play by Ayad Akhtar, who won the Pulitzer Prize for Disgraced, focuses on an egocentric, self-destructive white male novelist, played by Robert Downey, Jr. The fictional Jacob McNeal—think Mailer or Roth at their worst—wins the Nobel Prize early in the play, but he’s guarding a secret: his latest novel was composed with an uncredited coauthor, an AI chatbot. The production, which considers the controversial notion that artificial intelligence might be a useful creative tool, closes on November 24 after a nearly sold-out run at Lincoln Center. Despite a largely negative critical reception, the show has touched a nerve, which in my view is one of the jobs of a serious writer.