Julia Webster Ayuso in The Dial:

On the evening of October 16, 1984, the body of four-year-old Grégory Villemin was pulled out of the Vologne river in Eastern France. The little boy had disappeared from the front garden of his home in Lépanges-sur-Vologne earlier that afternoon. His mother had searched desperately all over the small village, but nobody had seen him.

On the evening of October 16, 1984, the body of four-year-old Grégory Villemin was pulled out of the Vologne river in Eastern France. The little boy had disappeared from the front garden of his home in Lépanges-sur-Vologne earlier that afternoon. His mother had searched desperately all over the small village, but nobody had seen him.

It quickly became clear that his death wasn’t a tragic accident. The boy’s hands and feet had been tied with string, and the family had received several threatening letters and voicemails before he disappeared. The following day, another letter was sent to the boy’s father, Jean-Marie Villemin. “I hope you will die of grief, boss,” it read in messy, joined-up handwriting. “Your money will not bring your son back. This is my revenge, you bastard.”

It was the beginning of what would become France’s best-known unsolved murder case. The case has been reopened several times, and multiple suspects have been arrested. Grégory’s mother, Christine, was charged with the crime and briefly jailed but later acquitted. Jean-Marie also served prison time after he shot dead his cousin Bernard Laroche, who had emerged as a prime suspect. The investigating judge, Jean-Michel Lambert, who was assigned the case at age 32 and made critical mistakes early in the investigation, killed himself in 2017.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How autonomous and semi-autonomous technology will operate in the future is up in the air, and the U.S. government will have to decide what limitations to place on its development and use. Those decisions may come sooner rather than later—as the technology advances, global conflicts continue to rage, and other countries are faced with similar choices—meaning that the incoming Trump administration may add to or change existing American policy. But experts say autonomous innovations have the potential to fundamentally change how war is waged: In the future, humans may not be the only arbiters of who lives and dies, with decisions instead in the hands of algorithms.

How autonomous and semi-autonomous technology will operate in the future is up in the air, and the U.S. government will have to decide what limitations to place on its development and use. Those decisions may come sooner rather than later—as the technology advances, global conflicts continue to rage, and other countries are faced with similar choices—meaning that the incoming Trump administration may add to or change existing American policy. But experts say autonomous innovations have the potential to fundamentally change how war is waged: In the future, humans may not be the only arbiters of who lives and dies, with decisions instead in the hands of algorithms. There are paintings that push beyond the confines of their chronology, with auras that have little to do with the orderly genre from which they emerge or even the painters who painted them. Obliterating the frames around them, they break through the fourth wall, headed straight for the viewer’s psyche like a parasite—settling into that part of the mind where we read and recognize ourselves.

There are paintings that push beyond the confines of their chronology, with auras that have little to do with the orderly genre from which they emerge or even the painters who painted them. Obliterating the frames around them, they break through the fourth wall, headed straight for the viewer’s psyche like a parasite—settling into that part of the mind where we read and recognize ourselves. S

S It started, like many good things, as a joke. NBC was filming a preview of its 1984 lineup, and Selma Diamond, a comedian in her sixties, had been tasked with introducing “Miami Vice,” a flashy affair of Ferraris, cocaine cartels, and designer sports jackets. She pretended to misunderstand. “ ‘Miami Nice’?” At last, a show about retirees, with their mink coats and cha-cha lessons. She got a laugh. And some execs thought it might not be a terrible idea.

It started, like many good things, as a joke. NBC was filming a preview of its 1984 lineup, and Selma Diamond, a comedian in her sixties, had been tasked with introducing “Miami Vice,” a flashy affair of Ferraris, cocaine cartels, and designer sports jackets. She pretended to misunderstand. “ ‘Miami Nice’?” At last, a show about retirees, with their mink coats and cha-cha lessons. She got a laugh. And some execs thought it might not be a terrible idea.

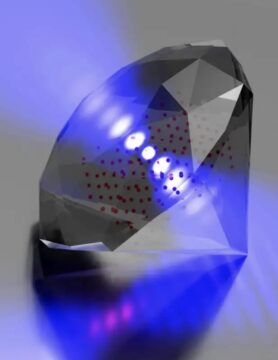

The famous marketing slogan about how a diamond is forever may only be a slight exaggeration for a diamond-based system capable of storing information for millions of years – and now researchers have created one with a record-breaking storage density of 1.85 terabytes per cubic centimetre.

The famous marketing slogan about how a diamond is forever may only be a slight exaggeration for a diamond-based system capable of storing information for millions of years – and now researchers have created one with a record-breaking storage density of 1.85 terabytes per cubic centimetre. Regular Noahpinion readers will know that I’m

Regular Noahpinion readers will know that I’m  I ONCE ASKED Breyten Breytenbach, the exiled South African poet and painter, why, in his opinion, after the fiasco of his clandestine return to his homeland in 1975 (traveling incognito as a would-be revolutionary organizer), the calamity of his arrest (his cover having likely been blown before he even entered the country, such that not only was he arrested but virtually everyone he’d contacted was arrested as well), the debacle of his trial (his appalling, groveling breakdown, his operatic recantations and expressions of contrition, all to no avail), after his being sentenced to nine years’ hard time in the country’s notorious penal system, why, I asked him, why had the authorities who allowed him to go on writing in prison nevertheless forbidden him to paint?

I ONCE ASKED Breyten Breytenbach, the exiled South African poet and painter, why, in his opinion, after the fiasco of his clandestine return to his homeland in 1975 (traveling incognito as a would-be revolutionary organizer), the calamity of his arrest (his cover having likely been blown before he even entered the country, such that not only was he arrested but virtually everyone he’d contacted was arrested as well), the debacle of his trial (his appalling, groveling breakdown, his operatic recantations and expressions of contrition, all to no avail), after his being sentenced to nine years’ hard time in the country’s notorious penal system, why, I asked him, why had the authorities who allowed him to go on writing in prison nevertheless forbidden him to paint? Dreams can transport us anywhere—from soaring above treetops to reliving the grind of office life—but what do they truly reveal? A recent survey by Talker Research for Newsweek asked 1,000 U.S. adults about their most

Dreams can transport us anywhere—from soaring above treetops to reliving the grind of office life—but what do they truly reveal? A recent survey by Talker Research for Newsweek asked 1,000 U.S. adults about their most