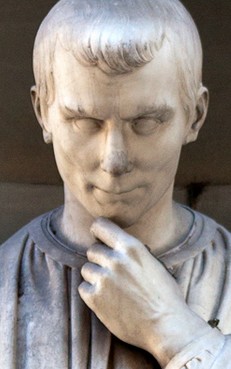

Christopher S. Celenza in Salon:

Clues concerning Machiavelli’s thinking as to his own immediate personal path lie in one of the Italian Renaissance’s most beautiful—and in some ways most deceiving—letters, which he wrote to his friend Vettori on December 10, 1513. There had been a brief interruption in their correspondence, one that left Machiavelli concerned. But upon receiving Vettori’s latest letter Machiavelli is “most pleased,” he says, and since he has no news to report resolves to send Vettori an account of what his life in exile is like. “I am on my farm, and I haven’t been in Florence for more than twenty days, total, since my recent problems.” Machiavelli spent about a month hunting thrushes—“two at least, at most six”—each day. After this diversion ended, Machiavelli settled into a routine: “In the mornings I rise with the sun, and I go to one of my woods that I am having cleared, where I stay for two hours to look over the work done the day before and to spend some time with the woodsmen. They are always in the middle of some argument, either among themselves or with the neighbors.” Machiavelli mixes and mingles with people of all classes, even as he listens to and participates in arguments. This fact was probably unsurprising to Vettori, knowing his friend as he did, even as it might seem surprising to connoisseurs of “high” literature.

Clues concerning Machiavelli’s thinking as to his own immediate personal path lie in one of the Italian Renaissance’s most beautiful—and in some ways most deceiving—letters, which he wrote to his friend Vettori on December 10, 1513. There had been a brief interruption in their correspondence, one that left Machiavelli concerned. But upon receiving Vettori’s latest letter Machiavelli is “most pleased,” he says, and since he has no news to report resolves to send Vettori an account of what his life in exile is like. “I am on my farm, and I haven’t been in Florence for more than twenty days, total, since my recent problems.” Machiavelli spent about a month hunting thrushes—“two at least, at most six”—each day. After this diversion ended, Machiavelli settled into a routine: “In the mornings I rise with the sun, and I go to one of my woods that I am having cleared, where I stay for two hours to look over the work done the day before and to spend some time with the woodsmen. They are always in the middle of some argument, either among themselves or with the neighbors.” Machiavelli mixes and mingles with people of all classes, even as he listens to and participates in arguments. This fact was probably unsurprising to Vettori, knowing his friend as he did, even as it might seem surprising to connoisseurs of “high” literature.

“After I leave the woods, I go to a spring, and thereafter to a place where I hang my bird nets. I have a book with me— Dante, or Petrarch, or a minor poet, like Tibullus, Ovid, or other ones of that sort. I read about their romantic passions, their love affairs, and I remember my own, taking pleasure for a while in those thoughts.” From the social to the solitary: this seems to be the second phase of his day, where repeated reading of a light classic, something that he already has read many times but to which he willingly returns, allows him to reflect on his own life. After this diversion and care of the soul comes more interactivity: “Then I take to the road, on the way to the inn. I chat with people who pass by, ask them about the news where they live, learning this and that, and I take note of the diverse taste and imaginings of men.” Machiavelli’s curiosity and, again, his proto-anthropological sensibility, is on display here.

More here.