Emily Keeler in National Post:

Writing is an act against death. In ink or in pixels, to put something in writing is to will it into a future beyond one’s own. In 2009, four days before Nelly Arcan hanged herself in her Montreal apartment, she sent a draft of her final novel to her publisher. The novel (published later that year in French as Paradise, clef en main and, in 2011, translated by David Scott Hamilton into English as Exit) takes place in a very near future where people committed to ushering in death well before nature takes its full course can become patrons of a boutique suicide service. Exit is written in the form of a fictional bedside confession from a woman, Antoinette Beauchamp, who failed her own suicide. Like Dorothy Parker’s tragic “Big Blonde,” Antoinette suffers the indignity of not getting what she wants when all she wants is the end. After surviving her meticulously planned suicide — “the Grim Reaper right at hand, shot in close-up, a death that was conceived, planned and paid for in advance” — Arcan’s protagonist wakes up in a hospital, having lost the use of her legs as a side-effect of her botched beheading (in homage to her namesake, Antoinette had paid the boutique to kill her by guillotine). Beyond the end of her wits, she narrates the story of her life and near-death to the ceiling of her hospital room. “Since the moment I stopped walking,” Arcan’s final protagonist tells us, “I started talking. A real chatterbox. A continuous current of words.”

Writing is an act against death. In ink or in pixels, to put something in writing is to will it into a future beyond one’s own. In 2009, four days before Nelly Arcan hanged herself in her Montreal apartment, she sent a draft of her final novel to her publisher. The novel (published later that year in French as Paradise, clef en main and, in 2011, translated by David Scott Hamilton into English as Exit) takes place in a very near future where people committed to ushering in death well before nature takes its full course can become patrons of a boutique suicide service. Exit is written in the form of a fictional bedside confession from a woman, Antoinette Beauchamp, who failed her own suicide. Like Dorothy Parker’s tragic “Big Blonde,” Antoinette suffers the indignity of not getting what she wants when all she wants is the end. After surviving her meticulously planned suicide — “the Grim Reaper right at hand, shot in close-up, a death that was conceived, planned and paid for in advance” — Arcan’s protagonist wakes up in a hospital, having lost the use of her legs as a side-effect of her botched beheading (in homage to her namesake, Antoinette had paid the boutique to kill her by guillotine). Beyond the end of her wits, she narrates the story of her life and near-death to the ceiling of her hospital room. “Since the moment I stopped walking,” Arcan’s final protagonist tells us, “I started talking. A real chatterbox. A continuous current of words.”

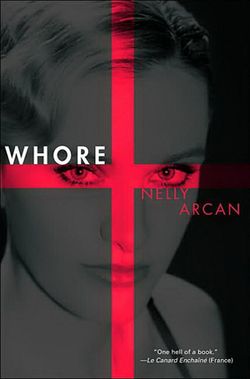

Arcan was 28 when her first novel came out in 2001. Between the publication of Putain (translated into English as Whore, by Bruce Benderson in 2004) and her death at the age of 36, she published four novels, an illustrated coffee-table book about looking at women, and some intermittent essays and stories, many of which have been translated into English by Melissa Bull, and anthologized into a slim collection, Burqa of Skin, which was published last December. Her third novel, Breakneck, will be translated into English, by Jacob Homel, for the first time this spring.

More here.