Masayuki Morikawa in Vox EU:

With the rapid diffusion of artificial intelligence (AI), its impacts on productivity and the labour market have attracted attention. Many studies have been conducted on the impacts of industrial robots on productivity (e.g. Graetz and Michaels 2018, Kromann et al. 2020, Cette et al. 2021, Dauth et al. 2021) due to the availability of International Federation of Robotics (IFR) data on robot utilisation by country and industry. However, the quantitative impact of AI on productivity is not yet well understood, mainly due to a lack of statistical data on the use of AI.

Recently, several studies have reported findings from randomised experiments on specific tasks in which AI has a large positive effect on productivity (e.g. Brynjolfsson et al. 2023, Kanazawa et al. 2022, Noy and Zhang 2023, Peng et al. 2023). These studies are valuable contributions that reveal the causal effect of AI on productivity, but it is impossible to infer macroeconomic impacts from these results because the studies only cover the very narrowly defined tasks of customer support, taxi driving, writing tasks, and software programming.

Acemoglu (2024) estimates the medium-term effect of AI on productivity in the US as the percentage of tasks affected by AI multiplied by task-level cost savings based on these existing task-level studies. According to his study, the macroeconomic impact of AI is non-negligible but small, with a cumulative total factor productivity (TFP) increase of less than 0.7%. However, he noted that there is huge uncertainty about which tasks will be automated, and what the cost savings will be.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

C

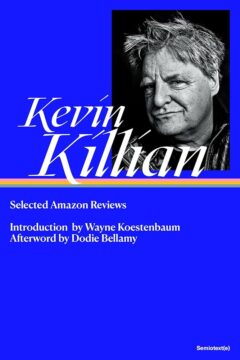

C In 2021, writer Will Hall began scraping Kevin Killian’s reviews from Amazon’s servers and, thanks largely to his efforts, Semiotext(e) published Kevin Killian: Selected Amazon Reviews in November. The 697-page collection rescues from obscurity some of the over two thousand reviews the poet, playwright, novelist, biographer, editor, critic, and artist posted to the platform from 2003 until his death in 2019. He was a great consumer of books, music, and film but also discussed the odd product. Killian’s reviews can be read as meditations on the objects and media that populated our lives for the first twenty-five years of the twenty-first century. He imbued ordinary items – duct tape, a toaster, a DVD—with personal meaning.

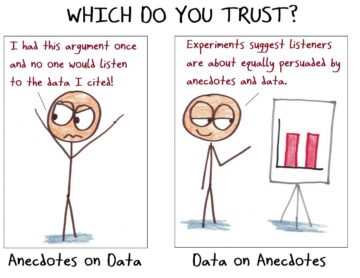

In 2021, writer Will Hall began scraping Kevin Killian’s reviews from Amazon’s servers and, thanks largely to his efforts, Semiotext(e) published Kevin Killian: Selected Amazon Reviews in November. The 697-page collection rescues from obscurity some of the over two thousand reviews the poet, playwright, novelist, biographer, editor, critic, and artist posted to the platform from 2003 until his death in 2019. He was a great consumer of books, music, and film but also discussed the odd product. Killian’s reviews can be read as meditations on the objects and media that populated our lives for the first twenty-five years of the twenty-first century. He imbued ordinary items – duct tape, a toaster, a DVD—with personal meaning. I’ve come to see this as a basic dynamic in math education reform: an illusory spirit of consensus. Clearly math education needs more something. But more what?

I’ve come to see this as a basic dynamic in math education reform: an illusory spirit of consensus. Clearly math education needs more something. But more what? I

I  T

T I

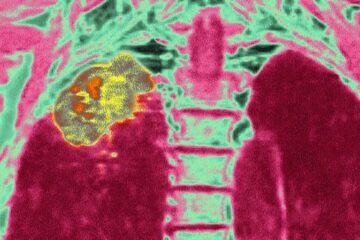

I Scientists have disguised tumours to ‘look’ similar to

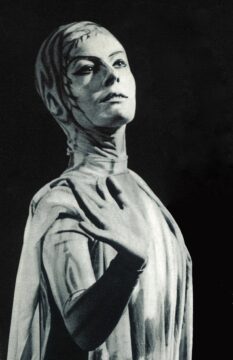

Scientists have disguised tumours to ‘look’ similar to  Twin Peaks first aired in 1991. A tragic and often frightening mystery, it centred on the violent murder of a beautiful teenage girl in a strange, small town nestled in the mountains of the Pacific Northwest. The protagonist was a handsome FBI agent who drank black coffee and spoke in riddles. There was a lot of

Twin Peaks first aired in 1991. A tragic and often frightening mystery, it centred on the violent murder of a beautiful teenage girl in a strange, small town nestled in the mountains of the Pacific Northwest. The protagonist was a handsome FBI agent who drank black coffee and spoke in riddles. There was a lot of

In December, 37 colleagues and I published a

In December, 37 colleagues and I published a  We

We