Drew M Dalton in Aeon:

Reality, as we now understand, does not tend towards existential flourishing and eternal becoming. Instead, systems collapse, things break down, and time tends irreversibly towards disorder and eventual annihilation. Rather than something to align with, the Universe appears to be fundamentally hostile to our wellbeing.

Reality, as we now understand, does not tend towards existential flourishing and eternal becoming. Instead, systems collapse, things break down, and time tends irreversibly towards disorder and eventual annihilation. Rather than something to align with, the Universe appears to be fundamentally hostile to our wellbeing.

According to the laws of thermodynamics, all that exists does so solely to consume, destroy and extinguish, and in this way to accelerate the slide toward cosmic obliteration. For these reasons, the thermodynamic revolution in our understanding of the order and operation of reality is more than a scientific development. It is also more than a simple revision of our understanding of the flow of heat, and it does more than help us design more efficient engines. It ruptures our commonly held beliefs concerning the nature and value of existence, and it demands a new metaphysics, bold new ethical principles and alternative aesthetic models.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Imagine, then, standing in 1815, a quarter century after the Revolution, looking back at what it had all become. That first bright rush of freedom had given way, first to the murderous insanity of the Terror and the Committee for Public Safety, then to the thuggish new imperialism and endless bloody wars of Napoleon, and finally to the fall of all Europe to conservative reaction under the Congress of Vienna. Imagine looking back on the arc of your beliefs, your movement, and your life, now as an old man, with no prospects for another, better Revolution ahead of you.

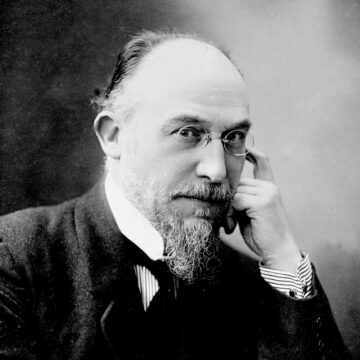

Imagine, then, standing in 1815, a quarter century after the Revolution, looking back at what it had all become. That first bright rush of freedom had given way, first to the murderous insanity of the Terror and the Committee for Public Safety, then to the thuggish new imperialism and endless bloody wars of Napoleon, and finally to the fall of all Europe to conservative reaction under the Congress of Vienna. Imagine looking back on the arc of your beliefs, your movement, and your life, now as an old man, with no prospects for another, better Revolution ahead of you. What is the point? is of course one of the main points of Satie. You don’t get the same sensation, for instance, listening to The Rite of Spring, Salome, Wozzeck, or Pierrot lunaire. As shocking or boundary-testing as those modernist masterpieces may be, they all have a point, and they work. They offer dramatic shapes, vectors, formal conceits; they expose sharp contrasts or conflicts. Mostly, Satie’s pieces don’t work in those ways, and they leave the question of a point open at best.

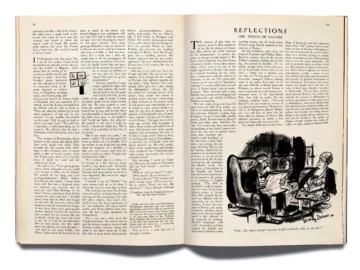

What is the point? is of course one of the main points of Satie. You don’t get the same sensation, for instance, listening to The Rite of Spring, Salome, Wozzeck, or Pierrot lunaire. As shocking or boundary-testing as those modernist masterpieces may be, they all have a point, and they work. They offer dramatic shapes, vectors, formal conceits; they expose sharp contrasts or conflicts. Mostly, Satie’s pieces don’t work in those ways, and they leave the question of a point open at best. Like novelistic interludes concerning pine forests, McCarthy’s breed of criticism feels endangered. The breezy authority, the absurd plenitude: these qualities suggest a more hospitable era for the printed word, even if you prefer today’s careful efficiency. That McCarthy rarely bothers to explain her voluminous references evokes a time when the writer’s job was less to make thinking easy than to make it rewarding. “One Touch of Nature” supplies the loveliness it praises, pausing to describe “the still, ribbony roads leading nowhere” in paintings by the Dutch artist Jacob van Ruisdael (whereas the essay itself is a snarl of colored lines on an M.T.A. map, leading everywhere at once) and “the snow in ‘The Dead’ falling softly over Ireland, a universal blanket or shroud.” As McCarthy surveys her subject, she conjures a living artistic ecosystem that is constantly evolving, including in its relationship to the natural world. The subtext is that this system, like the carbon-based one, is beautiful and worth attending to; McCarthy, novelist that she is, encrypts her themes on the way to elucidating them.

Like novelistic interludes concerning pine forests, McCarthy’s breed of criticism feels endangered. The breezy authority, the absurd plenitude: these qualities suggest a more hospitable era for the printed word, even if you prefer today’s careful efficiency. That McCarthy rarely bothers to explain her voluminous references evokes a time when the writer’s job was less to make thinking easy than to make it rewarding. “One Touch of Nature” supplies the loveliness it praises, pausing to describe “the still, ribbony roads leading nowhere” in paintings by the Dutch artist Jacob van Ruisdael (whereas the essay itself is a snarl of colored lines on an M.T.A. map, leading everywhere at once) and “the snow in ‘The Dead’ falling softly over Ireland, a universal blanket or shroud.” As McCarthy surveys her subject, she conjures a living artistic ecosystem that is constantly evolving, including in its relationship to the natural world. The subtext is that this system, like the carbon-based one, is beautiful and worth attending to; McCarthy, novelist that she is, encrypts her themes on the way to elucidating them. When Lisa Dutton was declared free of

When Lisa Dutton was declared free of

It is not clear how Carruthers and Graham imagined the public would respond. The tree was a beloved landmark, its silhouette an instantly recognizable symbol of England’s North East. As virtually every news

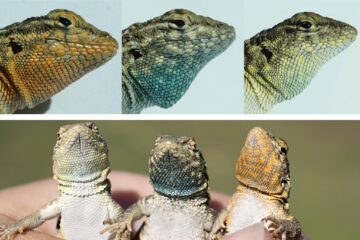

It is not clear how Carruthers and Graham imagined the public would respond. The tree was a beloved landmark, its silhouette an instantly recognizable symbol of England’s North East. As virtually every news  If you live in the United States, chances are you’re familiar with the game rock-paper-scissors. You put out your hand in one of three gestures: clenching it in a fist (rock), holding it out flat (paper) or holding up two fingers in a “V” (scissors). Rock beats scissors, scissors beat paper and paper beats rock.

If you live in the United States, chances are you’re familiar with the game rock-paper-scissors. You put out your hand in one of three gestures: clenching it in a fist (rock), holding it out flat (paper) or holding up two fingers in a “V” (scissors). Rock beats scissors, scissors beat paper and paper beats rock. Over the weekend, the United States bombed Venezuela, and

Over the weekend, the United States bombed Venezuela, and  “I can’t believe you haven’t read this,” my husband said one day right before Thanksgiving. He was holding Maggie O’Farrell’s 2020 novel, “

“I can’t believe you haven’t read this,” my husband said one day right before Thanksgiving. He was holding Maggie O’Farrell’s 2020 novel, “ Our society faces a dramatic, but elusive, crisis.

Our society faces a dramatic, but elusive, crisis. And here we arrive at a whole knot of issues at the heart of both Aviv’s and my own earlier characterizations of Oliver’s story. Because Oliver could relate to the situation of those wretched patients both out of the residue of his mother’s malediction itself and the sheer extent of the drug induced extravagances and catatonias he’d thenceforth experienced as its direct result during his ensuing wild California days (when his slogan had been “Every dose an overdose”), and beyond that, the wider identification he’d come to feel more generally with what his California-era friend, the psychoanalyst Bob Rodman, termed “communities of the refused” (an identification which would subsequently extend to Parkinsonians, Touretters, amnesiacs, the Deaf, the catatonic, the colorblind, the faceblind, and other such marginalized communities, and for that matter ferns and cuttlefish and even certain inert chemical elements as well). That sense of identification came to ground a profound empathy which, on the one hand helped him to give voice to the otherwise voiceless by helping them to reclaim their own stories, their own narratives, in so doing allowing them to reemerge as the active agents of their own lives—a practice which, granted, occasionally overstepped its bounds into outright projection and, in the subsequent recounting, downright confabulation.

And here we arrive at a whole knot of issues at the heart of both Aviv’s and my own earlier characterizations of Oliver’s story. Because Oliver could relate to the situation of those wretched patients both out of the residue of his mother’s malediction itself and the sheer extent of the drug induced extravagances and catatonias he’d thenceforth experienced as its direct result during his ensuing wild California days (when his slogan had been “Every dose an overdose”), and beyond that, the wider identification he’d come to feel more generally with what his California-era friend, the psychoanalyst Bob Rodman, termed “communities of the refused” (an identification which would subsequently extend to Parkinsonians, Touretters, amnesiacs, the Deaf, the catatonic, the colorblind, the faceblind, and other such marginalized communities, and for that matter ferns and cuttlefish and even certain inert chemical elements as well). That sense of identification came to ground a profound empathy which, on the one hand helped him to give voice to the otherwise voiceless by helping them to reclaim their own stories, their own narratives, in so doing allowing them to reemerge as the active agents of their own lives—a practice which, granted, occasionally overstepped its bounds into outright projection and, in the subsequent recounting, downright confabulation.