by Michael Liss

We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

—Abraham Lincoln, March 4, 1861, First Inaugural Address

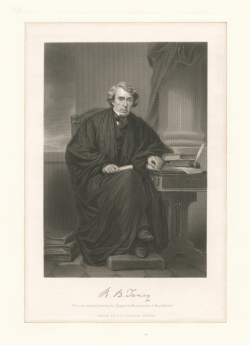

Irony. History offers an inexhaustible supply of it. Lincoln stood on the podium that March morning across from the one man who may have most helped put him there—the Chief Justice of the United States, Roger B. Taney. Four years earlier, on March 4, 1857, Taney performed what he considered a far more pleasant duty: to swear in his fellow Dickinson College Alum James Buchanan. Then, just two days after, he lit the first match to Buchanan’s Presidency by reading from the bench what was probably the most consequential, and certainly the worst Supreme Court decision ever, Dred Scott vs. Sandford.

Irony. History offers an inexhaustible supply of it. Lincoln stood on the podium that March morning across from the one man who may have most helped put him there—the Chief Justice of the United States, Roger B. Taney. Four years earlier, on March 4, 1857, Taney performed what he considered a far more pleasant duty: to swear in his fellow Dickinson College Alum James Buchanan. Then, just two days after, he lit the first match to Buchanan’s Presidency by reading from the bench what was probably the most consequential, and certainly the worst Supreme Court decision ever, Dred Scott vs. Sandford.

Dred Scott was born a slave in Missouri, owned by an Army Surgeon named Emerson, who often traveled to new postings. For roughly a decade, they lived in Illinois, a state where slavery was prohibited by both the Northwest Ordinance and its own constitution. Later, Dr. Emerson was posted to Fort Snelling in Minnesota, then a territorial area where slavery had been forbidden by the Missouri Compromise. They finally returned to Missouri, and, after Emerson died and “title” to Scott passed to new owners, he sued for his freedom and that of his wife and children. Scott won at the trial court level, then lost in Missouri’s Supreme Court. At that point, he turned to the federal courts. Finally, in 1856, the matter reached the U.S. Supreme Court. The question was achingly simple on a human level, yet agonizingly complex from a public policy perspective: Was Dred Scott entitled to freedom by virtue of the amount of time spent in free areas? Scott contended he was. Scott’s master insisted that a “pure blooded” African and descendent of slaves could never be a U.S. citizen, and so therefore was not qualified to access the U.S. courts. The case was argued in February of 1856, then reargued en banc that December to specifically address two key points.

No one would argue with the idea that the issues were timely. Slavery was always timely; it was the intractable, incurable American Original Sin. The Constitution itself was jury-rigged to accommodate it, with painful concessions to which neither side ever fully reconciled itself. Conflicts arose continuously, not just over the Peculiar Institution itself, but by anything that it touched—internal improvements, trade and tariffs, even foreign policy. Every few years there would be a flare-up, sometimes resolved by quiet compromise or concession, sometimes by grand bargains, sometimes, as in the case of the South Carolina Nullification and Secession crisis, by the application of a combination of Jacksonian tact and Jacksonian brute force.

And still, it went on. Lynchings, raids, arson, smashing of presses, intimidation. The country seethed, quieted down, then seethed again. Preachers read from different sections of the Bible to claim spiritual support for their sides. Politicians alternated between bile and eloquence; newspapers wrote inflammatory, pointless editorials; and Congress debated endlessly.

Read more »