The New York Times has made a cool tool that lets you play with the Laurel/Yanny phenomenon. Try it.

Yohan John has written an explanation of the effect.

And finally, here is Rachel Gutman in The Atlantic:

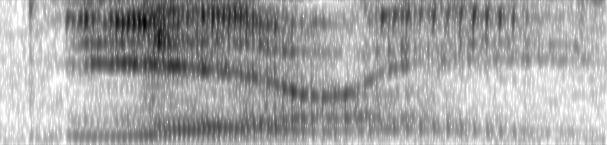

When you speak, you’re producing sound waves that are shaped by the length and shape of your vocal tract, which includes your vocal folds (vocal cords is a misnomer), throat, mouth, and nose. Linguists can study these sound waves and separate them out into their component frequencies, and display them in something called a spectrogram. Here’s the spectrogram for the yanny/laurel recording:

Higher frequencies (up to 5,000 hertz, or waves per second) appear toward the top, and lower ones (down to zero) toward the bottom. The dark bands are called formants; they’re the resonant frequencies of the vocal tract, and they depend on the length and shape of your vocal tract—i.e., all the space between your vocal folds, where the sound waves begin, and your mouth and nose, where they’re released.

The length of your vocal tract depends mostly on physiology: Women’s vocal folds tend to be higher up, so their tracts are shorter. The shape is largely based on where you put your tongue, like when you place the tip of your tongue between your teeth to make a th sound. By moving your tongue around in your mouth and opening and closing your lips, you change the sounds you’re making, and the formants you see in the spectrogram.

Chelsea Sanker, a phonetician at Brown University, looked at the spectrogram above to help me figure out what was going on.

More here.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Cemeteries face a sort of life-or-death crisis. The increasing popularity of cremation has meant that cemeteries are no longer critical to storing remains, while mourning on social media has removed the necessity of cemeteries as a primary place to mourn. Public mourning also has re-emerged with the widespread acceptance of roadside shrines, ghost bikes (white bikes placed on the roadside where a cyclist died), memorial vinyl decals for the back windows of cars, and memorial tattoos. While zombies roam the big and small screen, real death has returned to our streets, building walls, vehicles, and even bodies.

Cemeteries face a sort of life-or-death crisis. The increasing popularity of cremation has meant that cemeteries are no longer critical to storing remains, while mourning on social media has removed the necessity of cemeteries as a primary place to mourn. Public mourning also has re-emerged with the widespread acceptance of roadside shrines, ghost bikes (white bikes placed on the roadside where a cyclist died), memorial vinyl decals for the back windows of cars, and memorial tattoos. While zombies roam the big and small screen, real death has returned to our streets, building walls, vehicles, and even bodies.

What is morality? And are there any universal moral values? Scholars have debated these questions for millennia. But now, thanks to science, we have the answers.

What is morality? And are there any universal moral values? Scholars have debated these questions for millennia. But now, thanks to science, we have the answers.

Our brains are obsessed with being social even when we are not in social situations. A Dartmouth-led study finds that the brain may tune towards social learning even when it is at rest. The findings published in an advance article of Cerebral Cortex, demonstrate empirically for the first time how two regions of the brain experience increased connectivity during rest after encoding new social information.

Our brains are obsessed with being social even when we are not in social situations. A Dartmouth-led study finds that the brain may tune towards social learning even when it is at rest. The findings published in an advance article of Cerebral Cortex, demonstrate empirically for the first time how two regions of the brain experience increased connectivity during rest after encoding new social information. WHEREVER YOU LOOK—the press release, the brochure, the fact sheet, the cornerstone—

WHEREVER YOU LOOK—the press release, the brochure, the fact sheet, the cornerstone— Every era gets its own Thomas Cole, the British-born, nineteenth-century artist who ushered in a new age of American landscape painting. In the 1930s and 1940s, he was a precursor to artists like Grant Wood. Come the 1960s and 1970s, MoMA linked his brushwork to abstract expressionism. In the late 1980s, he was part of a Reaganesque “Morning in America” campaign, a Chrysler-sponsored survey of American landscape paintings at the Met. Now, also at the Met, “Thomas Cole’s Journey: Atlantic Crossings” positions Cole as a challenge to Trumpian greed, as well as to the American landscape as imagined by Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke and EPA chief Scott Pruitt. But while Cole was undoubtedly concerned with the land he painted, he was not exactly the convenient social critic the Met portrays.

Every era gets its own Thomas Cole, the British-born, nineteenth-century artist who ushered in a new age of American landscape painting. In the 1930s and 1940s, he was a precursor to artists like Grant Wood. Come the 1960s and 1970s, MoMA linked his brushwork to abstract expressionism. In the late 1980s, he was part of a Reaganesque “Morning in America” campaign, a Chrysler-sponsored survey of American landscape paintings at the Met. Now, also at the Met, “Thomas Cole’s Journey: Atlantic Crossings” positions Cole as a challenge to Trumpian greed, as well as to the American landscape as imagined by Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke and EPA chief Scott Pruitt. But while Cole was undoubtedly concerned with the land he painted, he was not exactly the convenient social critic the Met portrays. New words enter English in a variety of ways. They may be imported (

New words enter English in a variety of ways. They may be imported ( To investigate chimp communication, my colleagues and I follow chimpanzees through the forest as they go about their lives. We carry a hand-held “shotgun” microphone and a digital recorder, waiting for them to call.

To investigate chimp communication, my colleagues and I follow chimpanzees through the forest as they go about their lives. We carry a hand-held “shotgun” microphone and a digital recorder, waiting for them to call. The encouragement that the fifty-five-year-old psychology professor offers to his audiences takes the form of a challenge. To “take on the heaviest burden that you can bear.” To pursue a “voluntary confrontation with the tragedy and malevolence of being.” To seek a strenuous life spent “at the boundary between chaos and order.” Who dares speak of such things without nervous, self-protective irony? Without snickering self-effacement?

The encouragement that the fifty-five-year-old psychology professor offers to his audiences takes the form of a challenge. To “take on the heaviest burden that you can bear.” To pursue a “voluntary confrontation with the tragedy and malevolence of being.” To seek a strenuous life spent “at the boundary between chaos and order.” Who dares speak of such things without nervous, self-protective irony? Without snickering self-effacement? 1. Your perspective on yourself is distorted.

1. Your perspective on yourself is distorted. Since 2013,

Since 2013,  In 1954, on holiday in Mexico, Norman Mailer discovered weed. He had smoked it before, but this time was different. He experienced “some of the most incredible vomiting I ever had … like an apocalyptic purge”. But soon “I was on pot for the first time in my life, really on.” His second wife, the painter Adele Morales, was sleeping on a couch nearby. “I could seem to make her face whoever I wanted [it] to be,” Mailer wrote later, in the journal he kept during his marijuana years. “Probably could change her into an animal if I wished.” After that he got high on a regular basis. On “tea” (he called his weed diary “Lipton’s Journal”), he felt that “For the first time in my life, I could really understand jazz.” He also got to know the mind of the Almighty, which bore, he discovered, a marked resemblance to his own. Hotboxing in his car every night for a week, Mailer groped his way to the ideas that would shape his work during the 1960s and beyond. They were not, on the whole, very good ideas. But by 1954 Mailer was a desperate man. He was thirty-one and had published two novels: The Naked and the Dead (1948), which had been a smash, and Barbary Shore (1952), which had tanked. He felt like a failure. He needed “the energy of new success”. Eventually, of course, new success would come. But things had to get a lot worse before they could get better.

In 1954, on holiday in Mexico, Norman Mailer discovered weed. He had smoked it before, but this time was different. He experienced “some of the most incredible vomiting I ever had … like an apocalyptic purge”. But soon “I was on pot for the first time in my life, really on.” His second wife, the painter Adele Morales, was sleeping on a couch nearby. “I could seem to make her face whoever I wanted [it] to be,” Mailer wrote later, in the journal he kept during his marijuana years. “Probably could change her into an animal if I wished.” After that he got high on a regular basis. On “tea” (he called his weed diary “Lipton’s Journal”), he felt that “For the first time in my life, I could really understand jazz.” He also got to know the mind of the Almighty, which bore, he discovered, a marked resemblance to his own. Hotboxing in his car every night for a week, Mailer groped his way to the ideas that would shape his work during the 1960s and beyond. They were not, on the whole, very good ideas. But by 1954 Mailer was a desperate man. He was thirty-one and had published two novels: The Naked and the Dead (1948), which had been a smash, and Barbary Shore (1952), which had tanked. He felt like a failure. He needed “the energy of new success”. Eventually, of course, new success would come. But things had to get a lot worse before they could get better. Tom Wolfe died yesterday at age eighty-eight. Between 1965 and 1981, the dapper white-suited father of New Journalism chronicled, in pyrotechnic prose, everything from Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters to the first American astronauts. And then, having revolutionized journalism with his kaleidoscopic yet rigorous reportage, he decided it was time to write novels. As he said in his Art of Fiction interview, “Practically everyone my age who wanted to write somehow got the impression in college that there was only one thing to write, which was a novel and that if you went into journalism, this was only a cup of coffee on the road to the final triumph. At some point you would move into a shack—it was always a shack for some reason—and write a novel. This would be your real métier.” With The Bonfire of the Vanities, Wolfe wrote a sprawling, quintessential magnum opus of New York in the eighties. His first two novels were runaway best sellers, and his success won him the bitter envy of Norman Mailer, John Updike, and John Irving, among others.

Tom Wolfe died yesterday at age eighty-eight. Between 1965 and 1981, the dapper white-suited father of New Journalism chronicled, in pyrotechnic prose, everything from Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters to the first American astronauts. And then, having revolutionized journalism with his kaleidoscopic yet rigorous reportage, he decided it was time to write novels. As he said in his Art of Fiction interview, “Practically everyone my age who wanted to write somehow got the impression in college that there was only one thing to write, which was a novel and that if you went into journalism, this was only a cup of coffee on the road to the final triumph. At some point you would move into a shack—it was always a shack for some reason—and write a novel. This would be your real métier.” With The Bonfire of the Vanities, Wolfe wrote a sprawling, quintessential magnum opus of New York in the eighties. His first two novels were runaway best sellers, and his success won him the bitter envy of Norman Mailer, John Updike, and John Irving, among others.