Lauren Groff in The New York Times:

There are books that enter your life before their time; you can acknowledge their beauty and excellence, and yet walk away unchanged. This was how I first read Elizabeth Hardwick’s “Sleepless Nights,” after it was recommended in David Shields’ “Reality Hunger,” a thrilling manifesto that tries to make the case that our contemporary world is no longer well represented by realist fiction. While I loved “Sleepless Nights” on that first read — it is brilliant, brittle and strange, a book unlike any preconceived notion I had of what a novel could be — I moved on from it easily. I’ve lived two thousand and some odd days since, read hundreds of other books and published three of my own, all in a bright, hot landscape of somewhat-realist fiction.

There are books that enter your life before their time; you can acknowledge their beauty and excellence, and yet walk away unchanged. This was how I first read Elizabeth Hardwick’s “Sleepless Nights,” after it was recommended in David Shields’ “Reality Hunger,” a thrilling manifesto that tries to make the case that our contemporary world is no longer well represented by realist fiction. While I loved “Sleepless Nights” on that first read — it is brilliant, brittle and strange, a book unlike any preconceived notion I had of what a novel could be — I moved on from it easily. I’ve lived two thousand and some odd days since, read hundreds of other books and published three of my own, all in a bright, hot landscape of somewhat-realist fiction.

The middle of the night has become a lonely stretch of time, especially in the past few years, with vastly increased anxiety — over climate change and politics and what lies in wait in my little sons’ future. I normally salve insomnia with reading, but few new books have felt so revolutionary or so brave as to be able to rock my tired brain to attention. Only the great ones remain: George Eliot’s infinite wisdom in “Middlemarch,” Jane Austen’s gracious and low-stakes sublimity, Dante’s “The Inferno,” which makes our world above seem downright kind. And strangely, of all the books I have reread to comfort myself, I have turned most often to Hardwick’s “Sleepless Nights,” not without a little bitter tang of irony because of its title. The book didn’t dovetail with my heart on the first reading, but the world has changed around me, and now I find myself hungering for its particularity, the steady voice of Elizabeth Hardwick a balm to my aching, vulnerable mind.

Elizabeth Hardwick grew up in Kentucky, a charming young woman with a dagger of a mind. She left for New York City after college and took up with the Partisan Review crowd, becoming best friends with Mary McCarthy and writing for The New York Review of Books from its inception. “Sleepless Nights,” her third novel, is unambiguously her chef d’oeuvre; it was published when she was 63, after a career of writing sharp, ingenious pieces of criticism and after her long marriage to (and divorce from, then reunification with) the poet Robert Lowell, whose profound psychological struggles and infidelities and plagiarism of Hardwick’s letters in his books must surely have tested her strength. As a result, “Sleepless Nights” feels elemental, an eruption of everything that had been slowly building up over decades. Though there are books that are distant kin to it — Renata Adler’s “Speedboat,” Maggie Nelson’s “Bluets” — I have read nothing close enough to be called a sibling. This is rare; a feat of originality.

More here.

The Oxford-educated leader delivered his victory speech in Islamabad on Thursday declaring himself as the new Prime Minister, despite the official figures of the

The Oxford-educated leader delivered his victory speech in Islamabad on Thursday declaring himself as the new Prime Minister, despite the official figures of the  Last week the

Last week the  In 1963, Maria Goeppert Mayer won the Nobel Prize in physics for describing the layered, shell-like structures of atomic nuclei. No woman has won since.

In 1963, Maria Goeppert Mayer won the Nobel Prize in physics for describing the layered, shell-like structures of atomic nuclei. No woman has won since. SAY ‘KASHMIR’, and most people would reach for images of stone-throwing teenagers and harried soldiers. Every other aspect of life has been eclipsed by the protracted violence. Or been devalued as insufficiently urgent by comparison with the fight-to-the-death between the State and militant groups. For many of us, the first, instinctive, tragic response on hearing a Kashmiri place name is to locate it on a list of towns and villages associated with some horrible atrocity, some act of brutalisation. Such a list of place names would not—thankfully, not yet—feature Burzahom (Burzahama), 16 km northeast of Srinagar, and Gufkral, near Tral in the troubled Pulwama district.

SAY ‘KASHMIR’, and most people would reach for images of stone-throwing teenagers and harried soldiers. Every other aspect of life has been eclipsed by the protracted violence. Or been devalued as insufficiently urgent by comparison with the fight-to-the-death between the State and militant groups. For many of us, the first, instinctive, tragic response on hearing a Kashmiri place name is to locate it on a list of towns and villages associated with some horrible atrocity, some act of brutalisation. Such a list of place names would not—thankfully, not yet—feature Burzahom (Burzahama), 16 km northeast of Srinagar, and Gufkral, near Tral in the troubled Pulwama district. W

W A whole lot of books on the brain are published these days and you can read yourself into a coma trying to make sense of their various messages. So it was with my usual low-burn curiosity that I starting reading The Mind Is Flat by British behavioral scientist Nick Chater. At least the title is intriguing. But as I started reading it, I perked right up. Maybe that’s because it starts with a long riff on Anna Karenina and asks us to plumb the motivations of her suicide. Can we explain them? What if the great steam engine slammed on its brakes and Anna didn’t die? Would she be able to explain her own motivations to a psychologist while convalescing in a Swiss sanatorium?

A whole lot of books on the brain are published these days and you can read yourself into a coma trying to make sense of their various messages. So it was with my usual low-burn curiosity that I starting reading The Mind Is Flat by British behavioral scientist Nick Chater. At least the title is intriguing. But as I started reading it, I perked right up. Maybe that’s because it starts with a long riff on Anna Karenina and asks us to plumb the motivations of her suicide. Can we explain them? What if the great steam engine slammed on its brakes and Anna didn’t die? Would she be able to explain her own motivations to a psychologist while convalescing in a Swiss sanatorium? Henry Farrell in Crooked Timber:

Henry Farrell in Crooked Timber: John Horgan in Scientific American:

John Horgan in Scientific American:

Adam Tooze in Dissent:

Adam Tooze in Dissent: Merve Emre in Boston Review:

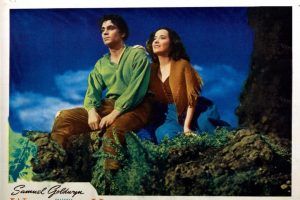

Merve Emre in Boston Review: The word Gidget, if it evokes anything in one’s mind, likely compels mental images of gingham bikinis, improvised luaus, and berserk 1950s-style optimism. Maybe Sandra Dee, pre-alcoholism, is pictured, or Sally Field before she was a flying nun. One definitely does not imagine a Jewish septuagenarian, married to a Yiddish scholar, with a tendency toward recreational hitchhiking. But that is who Kathy Zuckerman is, and Kathy Zuckerman is Gidget.

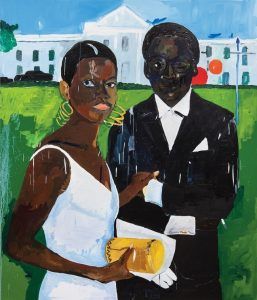

The word Gidget, if it evokes anything in one’s mind, likely compels mental images of gingham bikinis, improvised luaus, and berserk 1950s-style optimism. Maybe Sandra Dee, pre-alcoholism, is pictured, or Sally Field before she was a flying nun. One definitely does not imagine a Jewish septuagenarian, married to a Yiddish scholar, with a tendency toward recreational hitchhiking. But that is who Kathy Zuckerman is, and Kathy Zuckerman is Gidget. Yet to speak of this painting as I have—conceptually—is to pass over the difference between thinking with language and thinking in images, and no narrative explanation of the relation between these two pictures is as compelling as the horizontal line that marks the credenza in the photograph and the edge of the White House gardens in the painting, or the verticality of the white man in the photo’s top-right corner—with his squared-off shoulders—and his painterly analogue: a blue flagpole, with its crossbar and absence of flag. Taylor thinks primarily in colors, shapes, and lines—he has a spatial, tonal genius. Form responds to form: the negative space around Cicely and Miles in the photograph suggests the exact proportions of the White House, yet in the transition the abstract sometimes becomes figured, and vice versa, as if the border between these things didn’t matter. A burst of reflected light in the photo decides the height and placement of the windows in the painting, while two round signs at the movie première—one for Coca-Cola, the other for “Orange”—which can have no figurative echo in the painting, turn up anyhow on the White House façade as abstraction: a red sphere and an orange sphere, tracking the walls of what, in reality, now belonged to Trump. Like two suns setting at the same time.

Yet to speak of this painting as I have—conceptually—is to pass over the difference between thinking with language and thinking in images, and no narrative explanation of the relation between these two pictures is as compelling as the horizontal line that marks the credenza in the photograph and the edge of the White House gardens in the painting, or the verticality of the white man in the photo’s top-right corner—with his squared-off shoulders—and his painterly analogue: a blue flagpole, with its crossbar and absence of flag. Taylor thinks primarily in colors, shapes, and lines—he has a spatial, tonal genius. Form responds to form: the negative space around Cicely and Miles in the photograph suggests the exact proportions of the White House, yet in the transition the abstract sometimes becomes figured, and vice versa, as if the border between these things didn’t matter. A burst of reflected light in the photo decides the height and placement of the windows in the painting, while two round signs at the movie première—one for Coca-Cola, the other for “Orange”—which can have no figurative echo in the painting, turn up anyhow on the White House façade as abstraction: a red sphere and an orange sphere, tracking the walls of what, in reality, now belonged to Trump. Like two suns setting at the same time. Emily Brontë was born on July 30, 1818, in the village of Thornton, West Yorkshire, far from the mainstream of literary life. She died of tuberculosis at Haworth Parsonage, not six miles away, at the age of thirty. Her work had startled the critics with the force of its passion, but, over the years, shock was to settle into widespread admiration. In 1948, in a note added to the first chapter of The Great Tradition, F. R. Leavis described the author as the genius of her family, and her only novel, Wuthering Heights, as “astonishing”. When he added that it was a “kind of sport”, he was implying not its triviality, but its uniqueness. Forty years later, John Sutherland could introduce it in his Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction as the “twentieth century’s favourite nineteenth-century novel”. Emily’s poetry, which she published with great reluctance, has also continued to rise in the public estimation. The opening line of one of her poems, “No coward soul is mine”, can now be found emblazoned on mugs and key rings. It is even popular as a tattoo.

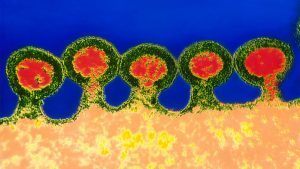

Emily Brontë was born on July 30, 1818, in the village of Thornton, West Yorkshire, far from the mainstream of literary life. She died of tuberculosis at Haworth Parsonage, not six miles away, at the age of thirty. Her work had startled the critics with the force of its passion, but, over the years, shock was to settle into widespread admiration. In 1948, in a note added to the first chapter of The Great Tradition, F. R. Leavis described the author as the genius of her family, and her only novel, Wuthering Heights, as “astonishing”. When he added that it was a “kind of sport”, he was implying not its triviality, but its uniqueness. Forty years later, John Sutherland could introduce it in his Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction as the “twentieth century’s favourite nineteenth-century novel”. Emily’s poetry, which she published with great reluctance, has also continued to rise in the public estimation. The opening line of one of her poems, “No coward soul is mine”, can now be found emblazoned on mugs and key rings. It is even popular as a tattoo. When Science published a monkey study nearly 2 years ago that showed an anti-inflammatory antibody effectively cured monkeys intentionally infected with the simian form of the AIDS virus, the dramatic results turned many heads. But some skeptical researchers thought the data looked too good to be true and predicted the intervention wouldn’t work on HIV in humans. They were right. Anthony Fauci, head of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Maryland, and a co-author of the Science paper, today reported the failure of a clinical trial that attempted to translate the remarkable monkey success to humans. “We did not see those dramatic results at all,” Fauci said at the International AIDS Conference in Amsterdam that is taking place this week.

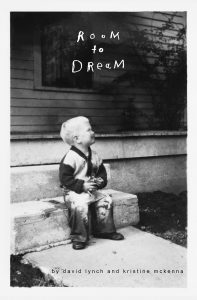

When Science published a monkey study nearly 2 years ago that showed an anti-inflammatory antibody effectively cured monkeys intentionally infected with the simian form of the AIDS virus, the dramatic results turned many heads. But some skeptical researchers thought the data looked too good to be true and predicted the intervention wouldn’t work on HIV in humans. They were right. Anthony Fauci, head of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Maryland, and a co-author of the Science paper, today reported the failure of a clinical trial that attempted to translate the remarkable monkey success to humans. “We did not see those dramatic results at all,” Fauci said at the International AIDS Conference in Amsterdam that is taking place this week. CRITICS GENERALLY DEFINE “Lynchian” as the cohabitation of the macabre and the mundane. The severed ear hidden in the field in Blue Velvet may be the most iconic representation of this junction, but it’s everywhere in David Lynch’s work: from Twin Peaks’s sweet, brochure-like title sequence of a mountainous town that, as it turns out, hides Laura Palmer’s corpse and many other monstrosities, to the arrival of Naomi Watts’s aspiring actress Betty in a dreamlike Hollywood in Mulholland Drive, before the nightmare of that city consumes her. In Lynch’s early work, the small town is the theater of this dance of innocence and evil, but in his later films, namely the loose trilogy of Lost Highway (1997), Mulholland Drive (2001), and Inland Empire (2006), the macabre and the mundane coexist in the individual soul. Upon reading Room to Dream — Lynch’s newly released experimental memoir — one’s tempted to say that the same coupling exists in David Lynch himself.

CRITICS GENERALLY DEFINE “Lynchian” as the cohabitation of the macabre and the mundane. The severed ear hidden in the field in Blue Velvet may be the most iconic representation of this junction, but it’s everywhere in David Lynch’s work: from Twin Peaks’s sweet, brochure-like title sequence of a mountainous town that, as it turns out, hides Laura Palmer’s corpse and many other monstrosities, to the arrival of Naomi Watts’s aspiring actress Betty in a dreamlike Hollywood in Mulholland Drive, before the nightmare of that city consumes her. In Lynch’s early work, the small town is the theater of this dance of innocence and evil, but in his later films, namely the loose trilogy of Lost Highway (1997), Mulholland Drive (2001), and Inland Empire (2006), the macabre and the mundane coexist in the individual soul. Upon reading Room to Dream — Lynch’s newly released experimental memoir — one’s tempted to say that the same coupling exists in David Lynch himself.