László Győri at Eurozine:

Film and theatre are not the only cultural sectors to have come into Fidesz’s crosshairs – the offensive was indeed ‘total’. For example, shortly after Orbán assumed power, the National Cultural Fund was restructured. Originally an independent body, it was responsible for distributing subsidies across all cultural sectors. A great advantage of the cultural fund was that it was independent of government. But Orbán subordinated it to a minister and a secretary of state, who henceforth had the power to revise the decisions of the committees responsible for the various cultural sectors. In summer 2010, members of the Cultural Fund’s councils responsible for publishing were replaced with Fidesz sympathizers. The procedure appeared paradoxical. The state created a fund which was charged not only with distributing money, but also with ensuring that decisions be made by qualified representatives. However, the government then intervened to ensure that these qualified, elected experts could not make democratic decisions about the money.

Film and theatre are not the only cultural sectors to have come into Fidesz’s crosshairs – the offensive was indeed ‘total’. For example, shortly after Orbán assumed power, the National Cultural Fund was restructured. Originally an independent body, it was responsible for distributing subsidies across all cultural sectors. A great advantage of the cultural fund was that it was independent of government. But Orbán subordinated it to a minister and a secretary of state, who henceforth had the power to revise the decisions of the committees responsible for the various cultural sectors. In summer 2010, members of the Cultural Fund’s councils responsible for publishing were replaced with Fidesz sympathizers. The procedure appeared paradoxical. The state created a fund which was charged not only with distributing money, but also with ensuring that decisions be made by qualified representatives. However, the government then intervened to ensure that these qualified, elected experts could not make democratic decisions about the money.

more here.

The Bureau had received credible evidence regarding Sontag’s trip to Hanoi—a feature in Esquire describing her experiences talking to leading figures of the North Vietnamese government, including Prime Minister Pham Van Dong, that would later be adapted into the book Trip to Hanoi.

The Bureau had received credible evidence regarding Sontag’s trip to Hanoi—a feature in Esquire describing her experiences talking to leading figures of the North Vietnamese government, including Prime Minister Pham Van Dong, that would later be adapted into the book Trip to Hanoi. It would be uncool, priggish, unthinking to care too much about the artist’s intoxication. Torments require relief and expression: numbing and utterance; alcohol and art. You can’t unpick the work from the circumstances of its creation, nor should you want to. In 1975, the critic Lewis Hyde tried caring about Berryman. A few years after the poet’s death, Hyde published an essay, an angry blast against the romanticization of the inebriated artist. When Hyde read The Dream Songs he didn’t hear the genius so much as “the booze talking”. “Its tone is a moan that doesn’t revolve.” Hyde seemed to believe – unfashionably – that Berryman’s work would have been better had he been sober.

It would be uncool, priggish, unthinking to care too much about the artist’s intoxication. Torments require relief and expression: numbing and utterance; alcohol and art. You can’t unpick the work from the circumstances of its creation, nor should you want to. In 1975, the critic Lewis Hyde tried caring about Berryman. A few years after the poet’s death, Hyde published an essay, an angry blast against the romanticization of the inebriated artist. When Hyde read The Dream Songs he didn’t hear the genius so much as “the booze talking”. “Its tone is a moan that doesn’t revolve.” Hyde seemed to believe – unfashionably – that Berryman’s work would have been better had he been sober. Merve Emre’s new book begins like a true-crime thriller, with the tantalizing suggestion that a number of unsettling revelations are in store. Early in “The Personality Brokers: The Strange History of Myers-Briggs and the Birth of Personality Testing,” she recalls the “low-level paranoia” she started to feel as she researched her subject: “Files disappear. Tapes are erased. People begin to watch you.” Archival gatekeepers were by turns controlling and evasive, acting like furtive trustees of terrible secrets. What, she wanted to know, were they trying to hide?

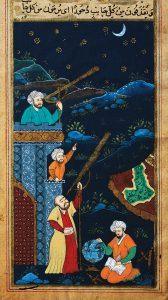

Merve Emre’s new book begins like a true-crime thriller, with the tantalizing suggestion that a number of unsettling revelations are in store. Early in “The Personality Brokers: The Strange History of Myers-Briggs and the Birth of Personality Testing,” she recalls the “low-level paranoia” she started to feel as she researched her subject: “Files disappear. Tapes are erased. People begin to watch you.” Archival gatekeepers were by turns controlling and evasive, acting like furtive trustees of terrible secrets. What, she wanted to know, were they trying to hide? As I prepared to teach my class ‘Science and Islam’ last spring, I noticed something peculiar about the book I was about to assign to my students. It wasn’t the text – a wonderful translation of a medieval Arabic encyclopaedia – but the cover. Its illustration showed scholars in turbans and medieval Middle Eastern dress, examining the starry sky through telescopes. The miniature purported to be from the premodern Middle East, but something was off.

As I prepared to teach my class ‘Science and Islam’ last spring, I noticed something peculiar about the book I was about to assign to my students. It wasn’t the text – a wonderful translation of a medieval Arabic encyclopaedia – but the cover. Its illustration showed scholars in turbans and medieval Middle Eastern dress, examining the starry sky through telescopes. The miniature purported to be from the premodern Middle East, but something was off. So effectively has the Beltway establishment captured the concept of national security that, for most of us, it automatically conjures up images of terrorist groups, cyber warriors, or “rogue states.” To ward off such foes, the United States maintains a historically unprecedented

So effectively has the Beltway establishment captured the concept of national security that, for most of us, it automatically conjures up images of terrorist groups, cyber warriors, or “rogue states.” To ward off such foes, the United States maintains a historically unprecedented  Seventy-five years ago, in April 1943, the research chemist Albert Hofmann did something distinctly out of scientific character. Impelled by what he later called a “peculiar presentiment”, he resolved to take a second look at the 25th in a series of molecules derived from the ergot fungus, a drug he had discovered some years earlier and dismissed as of no scientific interest. As he synthesised it for the second time, it made contact with his skin, giving rise to an unprecedented experience: a “stream of fantastic pictures [and] extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colours”. Five days later, on 19 April, he decided to test the chemical on himself under controlled conditions, thus becoming the first person in history knowingly to embark on an acid trip.

Seventy-five years ago, in April 1943, the research chemist Albert Hofmann did something distinctly out of scientific character. Impelled by what he later called a “peculiar presentiment”, he resolved to take a second look at the 25th in a series of molecules derived from the ergot fungus, a drug he had discovered some years earlier and dismissed as of no scientific interest. As he synthesised it for the second time, it made contact with his skin, giving rise to an unprecedented experience: a “stream of fantastic pictures [and] extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colours”. Five days later, on 19 April, he decided to test the chemical on himself under controlled conditions, thus becoming the first person in history knowingly to embark on an acid trip. The storms of rivalry and feud currently blowing through America’s internet portals rise to the wind-scale force of Wagnerian opera, but it’s hard to know whether the sound and fury is personal, political, or pathological. The stagings of vengeful lies to destroy a graven Facebook image, or the voicing of competitive truth that is the vitality of a democratic republic? The problem doesn’t yield to zero-sum solution.

The storms of rivalry and feud currently blowing through America’s internet portals rise to the wind-scale force of Wagnerian opera, but it’s hard to know whether the sound and fury is personal, political, or pathological. The stagings of vengeful lies to destroy a graven Facebook image, or the voicing of competitive truth that is the vitality of a democratic republic? The problem doesn’t yield to zero-sum solution.  Recent primaries have given Democrats reasons for hope, but they have also exposed fault lines within the party. Divisions are visible in the very labels used to describe them. Many use the word “liberal” as a catchall to describe left-of-center politics in general, but self-described leftists and members of the Democratic Socialists of America often characterize liberals and Democrats as their opponents—viewing them as the compromising centrists standing in the way of a more progressive or socialist agenda.

Recent primaries have given Democrats reasons for hope, but they have also exposed fault lines within the party. Divisions are visible in the very labels used to describe them. Many use the word “liberal” as a catchall to describe left-of-center politics in general, but self-described leftists and members of the Democratic Socialists of America often characterize liberals and Democrats as their opponents—viewing them as the compromising centrists standing in the way of a more progressive or socialist agenda. Psychologists are in the midst of an ongoing, difficult reckoning. Many believe that their field is experiencing a “

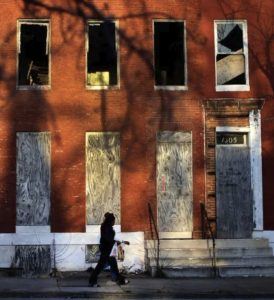

Psychologists are in the midst of an ongoing, difficult reckoning. Many believe that their field is experiencing a “ The dead books are on the top floor of Southern Methodist University’s law library.

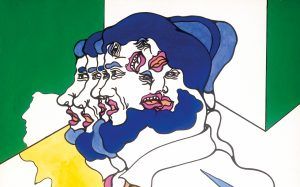

The dead books are on the top floor of Southern Methodist University’s law library. In 1969 the painter Jack Whitten arrived in the town of Agia Galini, on the Greek island of Crete. Shortly before leaving New York he’d had a dream in which he was commanded to find a tree and carve it. From the bus window he spied the tree from his dream. He approached the owner, but because Whitten couldn’t speak Greek, the man thought he was saying he wanted to cut it down. Whitten came up with a plan to communicate his aim: “I went into the surrounding hills, found some wood and set up shop on the harbor beneath some trees.” The owner understood immediately and even lent Whitten his tools. The totem he carved still stands in the town—a fisherman looks to the sea, an octopus winds around the trunk, and at the very top “is a large fish with its tail pointing to the sky.” This account, published in Notes from the Woodshed, a volume of the artist’s reflections on his art and practice, provides a key to understanding the gestural, communicative power of Whitten’s sculpture. Just as he was able to impart meaning by doing rather than speaking that first day on Crete, his sculptures—currently exhibited for the first time in a show that has arrived at the Met Breuer (New York)—express their strong emotional and spiritual content by foregrounding the physical acts of their creation. Carved, chiseled, polished, and hammered into insinuating, assertive shapes, these pieces make viewers feel the actual work, and sense the very grip of the artist’s hand on the hammer as it finds the chisel’s head.

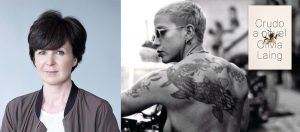

In 1969 the painter Jack Whitten arrived in the town of Agia Galini, on the Greek island of Crete. Shortly before leaving New York he’d had a dream in which he was commanded to find a tree and carve it. From the bus window he spied the tree from his dream. He approached the owner, but because Whitten couldn’t speak Greek, the man thought he was saying he wanted to cut it down. Whitten came up with a plan to communicate his aim: “I went into the surrounding hills, found some wood and set up shop on the harbor beneath some trees.” The owner understood immediately and even lent Whitten his tools. The totem he carved still stands in the town—a fisherman looks to the sea, an octopus winds around the trunk, and at the very top “is a large fish with its tail pointing to the sky.” This account, published in Notes from the Woodshed, a volume of the artist’s reflections on his art and practice, provides a key to understanding the gestural, communicative power of Whitten’s sculpture. Just as he was able to impart meaning by doing rather than speaking that first day on Crete, his sculptures—currently exhibited for the first time in a show that has arrived at the Met Breuer (New York)—express their strong emotional and spiritual content by foregrounding the physical acts of their creation. Carved, chiseled, polished, and hammered into insinuating, assertive shapes, these pieces make viewers feel the actual work, and sense the very grip of the artist’s hand on the hammer as it finds the chisel’s head. Yes, it was incredibly liberating, both to invent the character and to help myself to the ravishing grab-bag of Acker’s own work. Crudo is probably the only book I’ve really enjoyed writing, because it was so fast and so free. It was such a relief to ditch the I, but to keep all the real details of the world, to collage it together rather than inventing it afresh. I definitely have a horror of making shit up, but I also have a horror of confessional writing. It’s like the case studies in I Love Dick, I do want to write about the personal (mine, Acker’s, David Wojnarowicz’s and so on), but for political reasons.

Yes, it was incredibly liberating, both to invent the character and to help myself to the ravishing grab-bag of Acker’s own work. Crudo is probably the only book I’ve really enjoyed writing, because it was so fast and so free. It was such a relief to ditch the I, but to keep all the real details of the world, to collage it together rather than inventing it afresh. I definitely have a horror of making shit up, but I also have a horror of confessional writing. It’s like the case studies in I Love Dick, I do want to write about the personal (mine, Acker’s, David Wojnarowicz’s and so on), but for political reasons. Democrats may scoff at Republicans’ work requirements, but they have yet to challenge the dominant conception of poverty that feeds such meanspirited politics. Instead of offering a counternarrative to America’s moral trope of deservedness, liberals have generally submitted to it, perhaps even embraced it, figuring that the public will not support aid that doesn’t demand that the poor subject themselves to the low-paying jobs now available to them. Even stalwarts of the progressive movement seem to reserve economic prosperity for the full-time worker. Senator Bernie Sanders once declared, echoing a long line of Democrats who have come before and after him, “Nobody who works 40 hours a week should be living in poverty.” Sure, but what about those who work 20 or 30 hours, like Vanessa?

Democrats may scoff at Republicans’ work requirements, but they have yet to challenge the dominant conception of poverty that feeds such meanspirited politics. Instead of offering a counternarrative to America’s moral trope of deservedness, liberals have generally submitted to it, perhaps even embraced it, figuring that the public will not support aid that doesn’t demand that the poor subject themselves to the low-paying jobs now available to them. Even stalwarts of the progressive movement seem to reserve economic prosperity for the full-time worker. Senator Bernie Sanders once declared, echoing a long line of Democrats who have come before and after him, “Nobody who works 40 hours a week should be living in poverty.” Sure, but what about those who work 20 or 30 hours, like Vanessa?

From bulging biceps to 7-foot wingspans to a striking paucity of fat, elite athletes’ bodies often look quite different from those of the rest of us. But it’s not only athletes’ bodies that are different; their brains are just as finely tuned to the mental demands of a particular sport. Here are seven areas of the brain that enable seven different athletes to pull off extraordinary feats.

From bulging biceps to 7-foot wingspans to a striking paucity of fat, elite athletes’ bodies often look quite different from those of the rest of us. But it’s not only athletes’ bodies that are different; their brains are just as finely tuned to the mental demands of a particular sport. Here are seven areas of the brain that enable seven different athletes to pull off extraordinary feats.