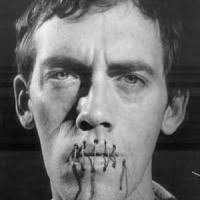

Jerry Saltz at New York Magazine:

Today, David Wojnarowicz is known mostly as a martyr to the culture wars of the 1980s, another artist diagnosed with AIDS who fought along with so many to get the government to act, for a long time in vain, and who then, like so many others, died of the disease, a terrible tear in the fabric of art that was savagely exacted on gay men of that generation. Wojnarowicz came out of the same deeply downtown bohemianism of the early 1980s that fueled Jean-Michel Basquiat’s equally short, culture-altering arc through the art world: small cadres of like-minded underground characters and self-defined artists, desperate to act on the culture but denied the usual access to artistic power structures for reasons financial, psychological, racial, sexual. Wojnarowicz rose amid a gritty East Village aesthetic of graffiti, Expressionistic gestures, roughly assembled surfaces, funky found objects, one-night shows at clubs, and midnight guerrilla actions on the finer art. But in a way, Wojnarowicz’s tremendous, almost Rimbaud-like reputation suits, since he was an even better, more lucid freedom fighter than he was an artist.

Today, David Wojnarowicz is known mostly as a martyr to the culture wars of the 1980s, another artist diagnosed with AIDS who fought along with so many to get the government to act, for a long time in vain, and who then, like so many others, died of the disease, a terrible tear in the fabric of art that was savagely exacted on gay men of that generation. Wojnarowicz came out of the same deeply downtown bohemianism of the early 1980s that fueled Jean-Michel Basquiat’s equally short, culture-altering arc through the art world: small cadres of like-minded underground characters and self-defined artists, desperate to act on the culture but denied the usual access to artistic power structures for reasons financial, psychological, racial, sexual. Wojnarowicz rose amid a gritty East Village aesthetic of graffiti, Expressionistic gestures, roughly assembled surfaces, funky found objects, one-night shows at clubs, and midnight guerrilla actions on the finer art. But in a way, Wojnarowicz’s tremendous, almost Rimbaud-like reputation suits, since he was an even better, more lucid freedom fighter than he was an artist.

more here.

Yet perhaps one of the greatest compliments I can give “On Color” is that despite the indisputable scholarly erudition found on every page, the clever edge to its witty prose and its own defiantly unclassifiable

Yet perhaps one of the greatest compliments I can give “On Color” is that despite the indisputable scholarly erudition found on every page, the clever edge to its witty prose and its own defiantly unclassifiable  In the world’s most famous thought experiment, physicist Erwin Schrödinger described how a cat in a box could be in an uncertain predicament. The peculiar rules of quantum theory meant that it could be both dead and alive, until the box was opened and the cat’s state measured. Now, two physicists have devised a modern version of the paradox by replacing the cat with a physicist doing experiments—with shocking implications. Quantum theory has a long history of thought experiments, and in most cases these are used to point to weaknesses in various interpretations of quantum mechanics. But the latest version, which involves multiple players, is unusual: it shows that if the standard interpretation of quantum mechanics is correct, then different experimenters can reach opposite conclusions about what the physicist in the box has measured. This means that quantum theory contradicts itself.

In the world’s most famous thought experiment, physicist Erwin Schrödinger described how a cat in a box could be in an uncertain predicament. The peculiar rules of quantum theory meant that it could be both dead and alive, until the box was opened and the cat’s state measured. Now, two physicists have devised a modern version of the paradox by replacing the cat with a physicist doing experiments—with shocking implications. Quantum theory has a long history of thought experiments, and in most cases these are used to point to weaknesses in various interpretations of quantum mechanics. But the latest version, which involves multiple players, is unusual: it shows that if the standard interpretation of quantum mechanics is correct, then different experimenters can reach opposite conclusions about what the physicist in the box has measured. This means that quantum theory contradicts itself. This thought kept blinking through my mind, like a neon sign on a dark street, as I read These Truths, the newest book by Harvard professor and The New Yorker contributor Jill Lepore. A 900-plus page tome, it is a full history of the United States, a country I was born in and soon after left. I was raised in a much younger country, Israel, which was handed over by a colonizing force to a people desperate for a home, back in the days—not so long ago, really—when colonizers could simply gift the land they’d taken as if it were theirs to give. The history I was taught from the ages of six to eighteen was both condensed and elongated, the history of a fledgling country full of war but also of an ancient people once enslaved and long persecuted.

This thought kept blinking through my mind, like a neon sign on a dark street, as I read These Truths, the newest book by Harvard professor and The New Yorker contributor Jill Lepore. A 900-plus page tome, it is a full history of the United States, a country I was born in and soon after left. I was raised in a much younger country, Israel, which was handed over by a colonizing force to a people desperate for a home, back in the days—not so long ago, really—when colonizers could simply gift the land they’d taken as if it were theirs to give. The history I was taught from the ages of six to eighteen was both condensed and elongated, the history of a fledgling country full of war but also of an ancient people once enslaved and long persecuted. ‘Red Birds’ marks the award-winning British-Pakistani author’s return to fiction after seven years, and is a potential instant classic.

‘Red Birds’ marks the award-winning British-Pakistani author’s return to fiction after seven years, and is a potential instant classic.

During the slow recovery after the 2008 financial crisis, Larry Summers, the Director of President Barack Obama’s National Economic Council, argued that the US economy was in the grips of “secular stagnation”: neither full employment nor strong growth could be achieved under stable financial conditions.

During the slow recovery after the 2008 financial crisis, Larry Summers, the Director of President Barack Obama’s National Economic Council, argued that the US economy was in the grips of “secular stagnation”: neither full employment nor strong growth could be achieved under stable financial conditions. Our understanding of heredity and genetics is improving at blinding speed. It was only in the year 2000 that scientists obtained the first rough map of the human genome: 3 billion base pairs of DNA with about 20,000 functional genes. Today, you can send a bit of your DNA to companies such as

Our understanding of heredity and genetics is improving at blinding speed. It was only in the year 2000 that scientists obtained the first rough map of the human genome: 3 billion base pairs of DNA with about 20,000 functional genes. Today, you can send a bit of your DNA to companies such as  That the news in its traditional forms is the problem with journalism actually dawned on me much earlier, when in 2006 I joined the editorial department of a major Dutch newspaper. I was 24 and studying philosophy when I landed a job covering domestic affairs. As a philosophy student does, I immediately started asking: what is this thing called news that I’m supposed to make here? Scrutinizing the practices of my colleagues, I eventually distilled a definition that I think describes news pretty accurately.

That the news in its traditional forms is the problem with journalism actually dawned on me much earlier, when in 2006 I joined the editorial department of a major Dutch newspaper. I was 24 and studying philosophy when I landed a job covering domestic affairs. As a philosophy student does, I immediately started asking: what is this thing called news that I’m supposed to make here? Scrutinizing the practices of my colleagues, I eventually distilled a definition that I think describes news pretty accurately.

Filmistan Studios occupies five acres in Goregaon, India, which is technically an outer suburb of Mumbai, but denser than most New York City neighborhoods. If you take the train from the city proper and fight the foot traffic that crowds the bazaar area around the station, you’ll reach a pair of steel gates. Just on the other side are Filmistan’s soundstages, which have been in continuous operation since 1943. In the Golden Age of Hindi Film, up to the 1960s, the industry worked along lines similar to those of the old Hollywood studio system, with each production house fielding its own stable of talent. Unlike most of its former rivals, Filmistan has remained open for business as a production facility, and the grounds now accommodate eight stages and several outdoor shooting areas, including a Hindu temple, a jailhouse exterior, and a village. But Filmistan is more than a collection of sets. Behind the scenes, there are real people living there. I came to Filmistan as an anthropologist in training, with a research project that looked solid enough, on paper, to win a Fulbright grant. One thing about ethnography they don’t teach you in school, though, is how awkward it can be getting started. Reaching out to people to do research with—soliciting “informants”—can feel like approaching strangers for a date. Left to myself in Mumbai, with my sun-glasses and clumsy Hindi, I was a field-work wallflower

Filmistan Studios occupies five acres in Goregaon, India, which is technically an outer suburb of Mumbai, but denser than most New York City neighborhoods. If you take the train from the city proper and fight the foot traffic that crowds the bazaar area around the station, you’ll reach a pair of steel gates. Just on the other side are Filmistan’s soundstages, which have been in continuous operation since 1943. In the Golden Age of Hindi Film, up to the 1960s, the industry worked along lines similar to those of the old Hollywood studio system, with each production house fielding its own stable of talent. Unlike most of its former rivals, Filmistan has remained open for business as a production facility, and the grounds now accommodate eight stages and several outdoor shooting areas, including a Hindu temple, a jailhouse exterior, and a village. But Filmistan is more than a collection of sets. Behind the scenes, there are real people living there. I came to Filmistan as an anthropologist in training, with a research project that looked solid enough, on paper, to win a Fulbright grant. One thing about ethnography they don’t teach you in school, though, is how awkward it can be getting started. Reaching out to people to do research with—soliciting “informants”—can feel like approaching strangers for a date. Left to myself in Mumbai, with my sun-glasses and clumsy Hindi, I was a field-work wallflower R

R Alvinella pompejana, a type of deep sea worm, can thrive at temperatures that would kill most living organisms. It has been used in skin creams — and sequences of its genes appear in 18 patents from not only BASF, but also a French research institution. Genetic prospectors — a term some find offensive, while acknowledging there’s not a great alternative — have a range of motivations. Some are hoping to develop a novel treatment for cancer. Others want to create the next Botox. Most are looking for organisms with exceptional traits that might offer the missing piece in their new product. That is why patents are filled with“extremophiles,” known for doing well in extreme darkness, cold, acidity and other harsh environments, said Robert Blasiak, a researcher from the Stockholm Resilience Centre who was involved in the patent study.

Alvinella pompejana, a type of deep sea worm, can thrive at temperatures that would kill most living organisms. It has been used in skin creams — and sequences of its genes appear in 18 patents from not only BASF, but also a French research institution. Genetic prospectors — a term some find offensive, while acknowledging there’s not a great alternative — have a range of motivations. Some are hoping to develop a novel treatment for cancer. Others want to create the next Botox. Most are looking for organisms with exceptional traits that might offer the missing piece in their new product. That is why patents are filled with“extremophiles,” known for doing well in extreme darkness, cold, acidity and other harsh environments, said Robert Blasiak, a researcher from the Stockholm Resilience Centre who was involved in the patent study. In 1933, with Hitler and the Nazis boycotting Jewish businesses, many powerful Jews in Germany and the powerful American Jewish charities opposed retaliation, advocating negotiation instead. Some viewed Hitler as a “weak man” and wanted to “strengthen his hand”: “Once the Nazis had cleansed Germany of opposition parties and ended parliamentary government, they turned their attention to the Jews. By mid-March, the rank-and-file were storming department stores and demanding a boycott of Jewish businesses. As much to guide as to incite these volatile emotions. Hitler and Goebbels championed the idea of a boycott. In a March 27 radio broadcast, the government announced that on the morning of April 1st, at the stroke of ten, SA and SS members would take up positions outside Jewish stores and warn the public not to enter. This offense was portrayed as a defensive measure against ‘Jewish atrocity propaganda abroad.’ To add further terror, Göring told Jewish community leaders that they would be held responsible for any anti-German propaganda appearing abroad. Eager to create jobs through exports, Hitler wanted to minimize adverse publicity overseas.

In 1933, with Hitler and the Nazis boycotting Jewish businesses, many powerful Jews in Germany and the powerful American Jewish charities opposed retaliation, advocating negotiation instead. Some viewed Hitler as a “weak man” and wanted to “strengthen his hand”: “Once the Nazis had cleansed Germany of opposition parties and ended parliamentary government, they turned their attention to the Jews. By mid-March, the rank-and-file were storming department stores and demanding a boycott of Jewish businesses. As much to guide as to incite these volatile emotions. Hitler and Goebbels championed the idea of a boycott. In a March 27 radio broadcast, the government announced that on the morning of April 1st, at the stroke of ten, SA and SS members would take up positions outside Jewish stores and warn the public not to enter. This offense was portrayed as a defensive measure against ‘Jewish atrocity propaganda abroad.’ To add further terror, Göring told Jewish community leaders that they would be held responsible for any anti-German propaganda appearing abroad. Eager to create jobs through exports, Hitler wanted to minimize adverse publicity overseas. He flew so fast and so close to the sun that it took an entire lifetime to fall back to Earth.

He flew so fast and so close to the sun that it took an entire lifetime to fall back to Earth. I recently read Simone Weil for the first time after having come across numerous references to her over the past year. I broke down and bought Waiting for God despite the intimidating and frankly confusing title. I was not disappointed. One of her essays in particular, “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies in View of the Love of God,” has opened and focused my thinking on education and learning in general, whether for children or later in life for the rest of us.

I recently read Simone Weil for the first time after having come across numerous references to her over the past year. I broke down and bought Waiting for God despite the intimidating and frankly confusing title. I was not disappointed. One of her essays in particular, “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies in View of the Love of God,” has opened and focused my thinking on education and learning in general, whether for children or later in life for the rest of us.

Opera as resistance? Music as re-enchantment?

Opera as resistance? Music as re-enchantment?