Ian Sample and Nicola Davis in The Guardian:

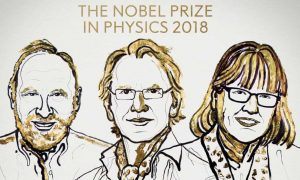

Three scientists have been awarded the 2018 Nobel prize in physics for creating groundbreaking tools from beams of light.

Three scientists have been awarded the 2018 Nobel prize in physics for creating groundbreaking tools from beams of light.

The American physicist Arthur Ashkin, Gérard Mourou from France, and Donna Strickland in Canada will share the 9m Swedish kronor (£770,000) prize announced by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm on Tuesday. Strickland is the first female physics laureate for 55 years.

Ashkin, an affiliate of Bell Laboratories in New Jersey, wins half of the prize for his development of “optical tweezers”, a tractor beam-like technology that allows scientists to grab atoms, viruses and bacteria in finger-like laser-beams. The effect was demonstrated by the award committee by levitating a ping pong ball with a hairdryer.

Mourou at the École Polytechnique near Paris, and Strickland at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, each receive a quarter of the prize for work that paved the way for the shortest, most intense laser beams ever created. Their technique, named chirped pulse amplification, is now used in laser machining and enables doctors to perform millions of corrective laser eye surgeries every year.

More here.

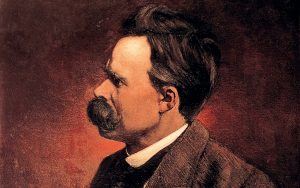

The Nietzsche scholar Walter Kaufmann told a story of how, in 1952, just two years after publishing his ground-breaking book, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, he visited the Cambridge philosopher CD Broad at Trinity College. During their conversation, Broad mentioned someone by the name of Salter. Was that, Kaufmann asked, the Salter who had written a book on Nietzsche? “Dear no,” Broad replied, “he did not deal with crackpot subjects like that; he wrote about psychical research.” In the years immediately before, during and just after the Second World War, Nietzsche’s reputation in the English-speaking world was at its lowest, largely owing to the fact that his work had been, with the support of his virulently anti-Semitic sister Elisabeth, appropriated by the Nazis. In their hands, Nietzsche’s notion of the Übermensch (I prefer to use the original German than any of the published translations; “superman” sounds silly, and “beyond-man” and “overman” do not sound like natural English) became associated with notions of Aryan racial superiority, while his idea of the “will to power” was used to justify militarism and authoritarianism.

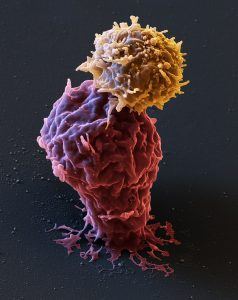

The Nietzsche scholar Walter Kaufmann told a story of how, in 1952, just two years after publishing his ground-breaking book, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, he visited the Cambridge philosopher CD Broad at Trinity College. During their conversation, Broad mentioned someone by the name of Salter. Was that, Kaufmann asked, the Salter who had written a book on Nietzsche? “Dear no,” Broad replied, “he did not deal with crackpot subjects like that; he wrote about psychical research.” In the years immediately before, during and just after the Second World War, Nietzsche’s reputation in the English-speaking world was at its lowest, largely owing to the fact that his work had been, with the support of his virulently anti-Semitic sister Elisabeth, appropriated by the Nazis. In their hands, Nietzsche’s notion of the Übermensch (I prefer to use the original German than any of the published translations; “superman” sounds silly, and “beyond-man” and “overman” do not sound like natural English) became associated with notions of Aryan racial superiority, while his idea of the “will to power” was used to justify militarism and authoritarianism. A highly unusual death has exposed a weak spot in a groundbreaking cancer treatment: One rogue cell, genetically altered by the therapy, can spiral out of control in a patient and cause a fatal relapse. The treatment, a form of immunotherapy, genetically engineers a patient’s own white blood cells to fight cancer. Sometimes described as a “living drug,” it has brought lasting remissions to leukemia patients who were on the brink of death. Among them is Emily Whitehead, the first child to receive the treatment, in 2012 when she was 6. The treatment does not always work, and side effects can be dangerous, even life-threatening. Doctors have learned to manage them. But in one patient, the therapy seems to have backfired in a previously unknown way. He was 20, with an aggressive type of leukemia. The treatment altered not just his cancer-fighting cells, but also — inadvertently — the genes of one leukemia cell. The genetic change made that cell invisible to the ones that had been programmed to seek and destroy cancer.

A highly unusual death has exposed a weak spot in a groundbreaking cancer treatment: One rogue cell, genetically altered by the therapy, can spiral out of control in a patient and cause a fatal relapse. The treatment, a form of immunotherapy, genetically engineers a patient’s own white blood cells to fight cancer. Sometimes described as a “living drug,” it has brought lasting remissions to leukemia patients who were on the brink of death. Among them is Emily Whitehead, the first child to receive the treatment, in 2012 when she was 6. The treatment does not always work, and side effects can be dangerous, even life-threatening. Doctors have learned to manage them. But in one patient, the therapy seems to have backfired in a previously unknown way. He was 20, with an aggressive type of leukemia. The treatment altered not just his cancer-fighting cells, but also — inadvertently — the genes of one leukemia cell. The genetic change made that cell invisible to the ones that had been programmed to seek and destroy cancer.

Every October there’s a huge book fair in my town, where used books donated by the community are put up for sale in a large hall at the fairgrounds. It’s no exaggeration to say that it’s a high point of my year.

Every October there’s a huge book fair in my town, where used books donated by the community are put up for sale in a large hall at the fairgrounds. It’s no exaggeration to say that it’s a high point of my year. As the first African American president of the United States (US), Barack Obama is a uniquely historical personality. Each of us has our opinions, or will formulate opinions, as to the success or limitations of his eight years in office as a Democratic president from 2009-2017, and as to the person who is Obama. Helping us in the formulation of our views on Obama and his presidency, is Ben Rhodes book, The World As It Is: Inside the Obama White House.

As the first African American president of the United States (US), Barack Obama is a uniquely historical personality. Each of us has our opinions, or will formulate opinions, as to the success or limitations of his eight years in office as a Democratic president from 2009-2017, and as to the person who is Obama. Helping us in the formulation of our views on Obama and his presidency, is Ben Rhodes book, The World As It Is: Inside the Obama White House.

One of the things I love about sports is they’re a low-stakes environment in which to practice high-stakes skills. For most people, most of the time, the results of a sporting match don’t affect the long-term quality of their lives. This is what I mean by “low-stakes.” In the grand scheme and scope of our lives, the outcomes of games rarely matter. Which is what makes sports such a great place to practice skills that really can and do impact our lives for the better. This is what I mean by “high-stakes.”

One of the things I love about sports is they’re a low-stakes environment in which to practice high-stakes skills. For most people, most of the time, the results of a sporting match don’t affect the long-term quality of their lives. This is what I mean by “low-stakes.” In the grand scheme and scope of our lives, the outcomes of games rarely matter. Which is what makes sports such a great place to practice skills that really can and do impact our lives for the better. This is what I mean by “high-stakes.” In the fall of 1970, I brought a Bundy tenor saxophone home from school. I was nine and in Mrs Farrar’s 5th grade class. To celebrate, my father slid an LP called “Soultrane”out of a blue and white cardboard jacket. The first sounds from the record player’s single speaker: a muscular folk song with rippling connective tissue that quickly spun free into endless cascades. Dad explained that it was my new horn, in the hands of John Coltrane. I didn’t know his name and nothing that day seemed possible, anyway.

In the fall of 1970, I brought a Bundy tenor saxophone home from school. I was nine and in Mrs Farrar’s 5th grade class. To celebrate, my father slid an LP called “Soultrane”out of a blue and white cardboard jacket. The first sounds from the record player’s single speaker: a muscular folk song with rippling connective tissue that quickly spun free into endless cascades. Dad explained that it was my new horn, in the hands of John Coltrane. I didn’t know his name and nothing that day seemed possible, anyway. Thirty years ago last week, Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses was published. Rushdie was then perhaps the most celebrated British novelist of his generation. His new novel, five years in the making, had been expected to set the world alight, though not quite in the way that it did.

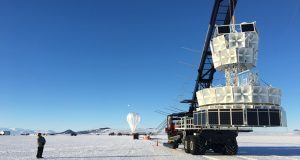

Thirty years ago last week, Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses was published. Rushdie was then perhaps the most celebrated British novelist of his generation. His new novel, five years in the making, had been expected to set the world alight, though not quite in the way that it did. Dangling from a balloon high above Antarctica, a particle detector has spotted something that standard physics is at a loss to explain.

Dangling from a balloon high above Antarctica, a particle detector has spotted something that standard physics is at a loss to explain. The cries of “Shame! Shame! Shame!” rang throughout the marbled walls of the

The cries of “Shame! Shame! Shame!” rang throughout the marbled walls of the  The man was 23 when the delusions came on. He became convinced that his thoughts were leaking out of his head and that other people could hear them. When he watched television, he thought the actors were signaling him, trying to communicate. He became irritable and anxious and couldn’t sleep. Dr. Tsuyoshi Miyaoka, a psychiatrist treating him at the Shimane University School of Medicine in Japan, eventually diagnosed paranoid schizophrenia. He then prescribed a series of antipsychotic drugs. None helped. The man’s symptoms were, in medical parlance, “treatment resistant.” A year later,

The man was 23 when the delusions came on. He became convinced that his thoughts were leaking out of his head and that other people could hear them. When he watched television, he thought the actors were signaling him, trying to communicate. He became irritable and anxious and couldn’t sleep. Dr. Tsuyoshi Miyaoka, a psychiatrist treating him at the Shimane University School of Medicine in Japan, eventually diagnosed paranoid schizophrenia. He then prescribed a series of antipsychotic drugs. None helped. The man’s symptoms were, in medical parlance, “treatment resistant.” A year later,

Before 2016 Jordan Peterson was indistinguishable from any other relatively successful academic with a respectable scholarly pedigree: B.A. in political science from the University of Alberta (1982), B.A. in psychology from the same institution (1984), Ph.D. in clinical psychology from McGill University (1991), postdoc at McGill’s Douglas Hospital (1992–1993), assistant and associate professorships at Harvard University in the psychology department (1993–1998), full tenured professorship at the University of Toronto (1999 to present), private clinical practice in Toronto, and a scholarly book by a reputable publishing house (Routledge). This ordinary career path turned extraordinary in 2016 when the controversial Bill C-16, a federal amendment to the Canadian Human Rights Act and Criminal Code, was passed, “to protect individuals from discrimination within the sphere of federal jurisdiction and from being the targets of hate propaganda, as a consequence of their gender identity or their gender expression.”

Before 2016 Jordan Peterson was indistinguishable from any other relatively successful academic with a respectable scholarly pedigree: B.A. in political science from the University of Alberta (1982), B.A. in psychology from the same institution (1984), Ph.D. in clinical psychology from McGill University (1991), postdoc at McGill’s Douglas Hospital (1992–1993), assistant and associate professorships at Harvard University in the psychology department (1993–1998), full tenured professorship at the University of Toronto (1999 to present), private clinical practice in Toronto, and a scholarly book by a reputable publishing house (Routledge). This ordinary career path turned extraordinary in 2016 when the controversial Bill C-16, a federal amendment to the Canadian Human Rights Act and Criminal Code, was passed, “to protect individuals from discrimination within the sphere of federal jurisdiction and from being the targets of hate propaganda, as a consequence of their gender identity or their gender expression.”