Gary Greenberg in the New York Times:

Give people a sugar pill, they have shown, and those patients — especially if they have one of the chronic, stress-related conditions that register the strongest placebo effects and if the treatment is delivered by someone in whom they have confidence — will improve. Tell someone a normal milkshake is a diet beverage, and his gut will respond as if the drink were low fat. Take athletes to the top of the Alps, put them on exercise machines and hook them to an oxygen tank, and they will perform better than when they are breathing room air — even if room air is all that’s in the tank. Wake a patient from surgery and tell him you’ve done an arthroscopic repair, and his knee gets better even if all you did was knock him out and put a couple of incisions in his skin. Give a drug a fancy name, and it works better than if you don’t.

Give people a sugar pill, they have shown, and those patients — especially if they have one of the chronic, stress-related conditions that register the strongest placebo effects and if the treatment is delivered by someone in whom they have confidence — will improve. Tell someone a normal milkshake is a diet beverage, and his gut will respond as if the drink were low fat. Take athletes to the top of the Alps, put them on exercise machines and hook them to an oxygen tank, and they will perform better than when they are breathing room air — even if room air is all that’s in the tank. Wake a patient from surgery and tell him you’ve done an arthroscopic repair, and his knee gets better even if all you did was knock him out and put a couple of incisions in his skin. Give a drug a fancy name, and it works better than if you don’t.

You don’t even have to deceive the patients. You can hand a patient with irritable bowel syndrome a sugar pill, identify it as such and tell her that sugar pills are known to be effective when used as placebos, and she will get better, especially if you take the time to deliver that message with warmth and close attention. Depression, back pain, chemotherapy-related malaise, migraine, post-traumatic stress disorder: The list of conditions that respond to placebos — as well as they do to drugs, with some patients — is long and growing.

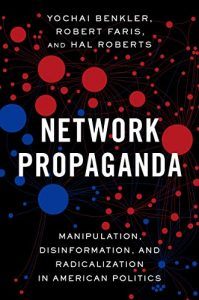

Deborah Chasman: The book focuses on the 2016 election and what made the public sphere so vulnerable to what you call “disinformation, propaganda, and just sheer bullshit.” You resist the idea that technology was the primary driver of that problem, that the manipulation of Facebook’s platform, the Russian intervention, and fake news led to a Trump victory. What did you find in your research that led you to challenge the now common story that extreme polarization has been technologically driven?

Deborah Chasman: The book focuses on the 2016 election and what made the public sphere so vulnerable to what you call “disinformation, propaganda, and just sheer bullshit.” You resist the idea that technology was the primary driver of that problem, that the manipulation of Facebook’s platform, the Russian intervention, and fake news led to a Trump victory. What did you find in your research that led you to challenge the now common story that extreme polarization has been technologically driven? The main attraction in the

The main attraction in the  François-Marie d’Arouet was the kind of precocious teen who always got invited to the best parties. Earning a reputation for his wit and catchy verses among the elites of 18th-century Paris, the young writer got himself exiled to the countryside in May 1716 for writing criticism of the ruling family. But Arouet—who would soon adopt the pen name “Voltaire”—was only getting started in his takedowns of those in power. In the coming years, those actions would have far more drastic repercussions: imprisonment for him, and a revolution for his country. And it all started with a story of incest. In 1715, the young Arouet began a daunting new project: adapting the story of Oedipus for a contemporary French audience. The ancient Greek tale chronicles the downfall of Oedipus, who fulfilled a prophecy that he would kill his father, the king of Thebes, and marry his mother. Greek playwright Sophocles wrote the earliest version of the play in his tragedy, Oedipus Rex. As recently as 1659, the famed French dramatist Pierre Corneille had adapted the play, but Arouet thought the story deserved an update, and he happened to be living at the perfect time to give it one.

François-Marie d’Arouet was the kind of precocious teen who always got invited to the best parties. Earning a reputation for his wit and catchy verses among the elites of 18th-century Paris, the young writer got himself exiled to the countryside in May 1716 for writing criticism of the ruling family. But Arouet—who would soon adopt the pen name “Voltaire”—was only getting started in his takedowns of those in power. In the coming years, those actions would have far more drastic repercussions: imprisonment for him, and a revolution for his country. And it all started with a story of incest. In 1715, the young Arouet began a daunting new project: adapting the story of Oedipus for a contemporary French audience. The ancient Greek tale chronicles the downfall of Oedipus, who fulfilled a prophecy that he would kill his father, the king of Thebes, and marry his mother. Greek playwright Sophocles wrote the earliest version of the play in his tragedy, Oedipus Rex. As recently as 1659, the famed French dramatist Pierre Corneille had adapted the play, but Arouet thought the story deserved an update, and he happened to be living at the perfect time to give it one.

The theory produces a good deal but hardly brings us closer to the secret of the Old One,’ wrote Albert Einstein in December 1926. ‘I am at all events convinced that He does not play dice.’

The theory produces a good deal but hardly brings us closer to the secret of the Old One,’ wrote Albert Einstein in December 1926. ‘I am at all events convinced that He does not play dice.’ The book was supposed to end with the inauguration of Barack Obama. That was Jill Lepore’s plan when she began work in 2015 on her new history of America, These Truths (W.W. Norton). She had arrived at the Civil War when Donald J. Trump was elected. Not to alter the ending, she has said, would have felt like “a dereliction of duty as a historian.”

The book was supposed to end with the inauguration of Barack Obama. That was Jill Lepore’s plan when she began work in 2015 on her new history of America, These Truths (W.W. Norton). She had arrived at the Civil War when Donald J. Trump was elected. Not to alter the ending, she has said, would have felt like “a dereliction of duty as a historian.”

Europe’s outlook can appear bleak these days: the Brexit downward spiral continues, both Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel are weakened, and Italy’s

Europe’s outlook can appear bleak these days: the Brexit downward spiral continues, both Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel are weakened, and Italy’s  I think much of my body awareness, in addition to my literary awareness, comes from Joan Didion. In Play It As It Lays, her 1970 novel (less popular than Slouching Towards Bethlehem, but still beloved), bodies are unpredictable geodes. Protagonist Maria’s (Mar-eye-ah’s) insides are vibrant with colour and edges and productive capability, but also completely invisible. She mines for menstruation in there, hoping she isn’t pregnant, which of course she is. A doctor ‘scrapes’ her zygote (a geological-seeming name in itself) out in an abortion scene that is refreshingly without either cynicism or romanticised maternal strickenness. But it doesn’t particularly matter (at least superficially) what goes on in there, in the novel’s bright and weird physical and psychological interiors. Didion is more interested in the woman’s outside, and what it can control. Maria has dreams that a “shadowy Syndicate” occupy her home in an illicit disposal operation. The grey flesh of victims clogs sinks, and water in drains begins to rise. So, certainly, a fear of the watery interior banishes Maria from her home into a tiny apartment, and structures several chapters of the novel. But my impression is that, despite being a clear-eyed writer of insides (especially those of women like herself) and a notable mid-century explorer of what Maggie Nelson has called “a situation of meat”, the disturbing softness and fallibility of the body and of consciousness, Didion is more interested in the hard geological outside, and whether it is hard, and how hard it is. What is women’s hardness? In the end, Maria—whose character is a variation on and also a criticism of the ‘madwoman in the attic’ trope—smokes half a joint, accrues a new psychosis or fixation, and moves back into that fleshy house with a life of its own, braving the interior.

I think much of my body awareness, in addition to my literary awareness, comes from Joan Didion. In Play It As It Lays, her 1970 novel (less popular than Slouching Towards Bethlehem, but still beloved), bodies are unpredictable geodes. Protagonist Maria’s (Mar-eye-ah’s) insides are vibrant with colour and edges and productive capability, but also completely invisible. She mines for menstruation in there, hoping she isn’t pregnant, which of course she is. A doctor ‘scrapes’ her zygote (a geological-seeming name in itself) out in an abortion scene that is refreshingly without either cynicism or romanticised maternal strickenness. But it doesn’t particularly matter (at least superficially) what goes on in there, in the novel’s bright and weird physical and psychological interiors. Didion is more interested in the woman’s outside, and what it can control. Maria has dreams that a “shadowy Syndicate” occupy her home in an illicit disposal operation. The grey flesh of victims clogs sinks, and water in drains begins to rise. So, certainly, a fear of the watery interior banishes Maria from her home into a tiny apartment, and structures several chapters of the novel. But my impression is that, despite being a clear-eyed writer of insides (especially those of women like herself) and a notable mid-century explorer of what Maggie Nelson has called “a situation of meat”, the disturbing softness and fallibility of the body and of consciousness, Didion is more interested in the hard geological outside, and whether it is hard, and how hard it is. What is women’s hardness? In the end, Maria—whose character is a variation on and also a criticism of the ‘madwoman in the attic’ trope—smokes half a joint, accrues a new psychosis or fixation, and moves back into that fleshy house with a life of its own, braving the interior. Toward the end of the Obama presidency, the work of James Baldwin began to enjoy a renaissance that was both much overdue and comfortless. Baldwin stands as one of the greatest American writers of the twentieth century, and any celebration of his work is more than welcome. But it was less a reveling than a panic. The eight years of the first black president were giving way to some of the most blatant and vitriolic displays of racism in decades, while the shooting deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and others too numerous to list sparked a movement in defense of black lives. In Baldwin, people found a voice from the past so relevant that he seemed prophetic.

Toward the end of the Obama presidency, the work of James Baldwin began to enjoy a renaissance that was both much overdue and comfortless. Baldwin stands as one of the greatest American writers of the twentieth century, and any celebration of his work is more than welcome. But it was less a reveling than a panic. The eight years of the first black president were giving way to some of the most blatant and vitriolic displays of racism in decades, while the shooting deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and others too numerous to list sparked a movement in defense of black lives. In Baldwin, people found a voice from the past so relevant that he seemed prophetic. In our house, it has always been the most dreaded part of Thanksgiving. More painful than hand-scrubbing the casserole pan. More excruciating than listening to our libertarian cousin. I speak of the custom of forced gratitude — of going around the table and telling everyone what we’re thankful for.

In our house, it has always been the most dreaded part of Thanksgiving. More painful than hand-scrubbing the casserole pan. More excruciating than listening to our libertarian cousin. I speak of the custom of forced gratitude — of going around the table and telling everyone what we’re thankful for. The first ever “solid state” plane, with no moving parts in its propulsion system, has successfully flown for a distance of 60 metres, proving that heavier-than-air flight is possible without jets or propellers.

The first ever “solid state” plane, with no moving parts in its propulsion system, has successfully flown for a distance of 60 metres, proving that heavier-than-air flight is possible without jets or propellers. During nine years as dean of Harvard Medical School, I enthusiastically supported efforts to enhance diversity, equity and inclusion. Two years after leaving that role, I recently

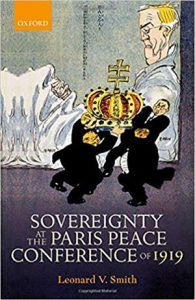

During nine years as dean of Harvard Medical School, I enthusiastically supported efforts to enhance diversity, equity and inclusion. Two years after leaving that role, I recently  The 1815 Congress of Vienna was the most important diplomatic encounter of the 19th century. When a Parisian court painter called Jean-Baptiste Isabey depicted the scene, most of the figures around the conference table were aristocrats. Fast forward to its closest 20th-century equivalent — the Paris Peace Conference, convened at the end of the first world war: barely half a dozen out of more than 60 delegates had titles, and of these one was a recent baronet and another a maharajah.

The 1815 Congress of Vienna was the most important diplomatic encounter of the 19th century. When a Parisian court painter called Jean-Baptiste Isabey depicted the scene, most of the figures around the conference table were aristocrats. Fast forward to its closest 20th-century equivalent — the Paris Peace Conference, convened at the end of the first world war: barely half a dozen out of more than 60 delegates had titles, and of these one was a recent baronet and another a maharajah. The GOP understands how important labor unions are to the Democratic Party. The Democratic Party, historically, has not. If you want a two-sentence explanation for why the Midwest is turning red (and thus, why Donald Trump is president), you could do worse than that.

The GOP understands how important labor unions are to the Democratic Party. The Democratic Party, historically, has not. If you want a two-sentence explanation for why the Midwest is turning red (and thus, why Donald Trump is president), you could do worse than that. There’s a verbal tic particular to a certain kind of response to a certain kind of story about the thinness and desperation of American society; about the person who died of preventable illness or the Kickstarter campaign to help another who can’t afford cancer treatment even with “good” insurance; about the plight of the homeless or the lack of resources for the rural poor; about underpaid teachers spending thousands of dollars of their own money for the most basic classroom supplies; about train derailments, the ruination of the New York subway system and the decrepit states of our airports and ports of entry.

There’s a verbal tic particular to a certain kind of response to a certain kind of story about the thinness and desperation of American society; about the person who died of preventable illness or the Kickstarter campaign to help another who can’t afford cancer treatment even with “good” insurance; about the plight of the homeless or the lack of resources for the rural poor; about underpaid teachers spending thousands of dollars of their own money for the most basic classroom supplies; about train derailments, the ruination of the New York subway system and the decrepit states of our airports and ports of entry.