Brooke Jarvis in the New York Times:

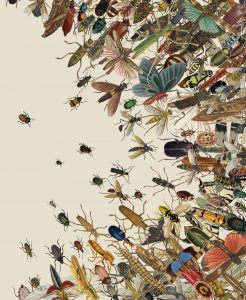

Sune Boye Riis was on a bike ride with his youngest son, enjoying the sun slanting over the fields and woodlands near their home north of Copenhagen, when it suddenly occurred to him that something about the experience was amiss. Specifically, something was missing.

Sune Boye Riis was on a bike ride with his youngest son, enjoying the sun slanting over the fields and woodlands near their home north of Copenhagen, when it suddenly occurred to him that something about the experience was amiss. Specifically, something was missing.

It was summer. He was out in the country, moving fast. But strangely, he wasn’t eating any bugs.

For a moment, Riis was transported to his childhood on the Danish island of Lolland, in the Baltic Sea. Back then, summer bike rides meant closing his mouth to cruise through thick clouds of insects, but inevitably he swallowed some anyway. When his parents took him driving, he remembered, the car’s windshield was frequently so smeared with insect carcasses that you almost couldn’t see through it. But all that seemed distant now. He couldn’t recall the last time he needed to wash bugs from his windshield; he even wondered, vaguely, whether car manufacturers had invented some fancy new coating to keep off insects. But this absence, he now realized with some alarm, seemed to be all around him. Where had all those insects gone? And when? And why hadn’t he noticed?

More here. [Thanks to Brooks Riley.]

The last forty years have seen a transformation in American business. Three major airlines dominate the skies. About ten pharmaceutical companies make up the lion’s share of the industry. Three major companies constitute the seed and pesticide industry. And 70 percent of beer is sold to one of two conglomerates. Scholars have shown that this wave of consolidation has depressed wages, increased inequality, and arrested small business formation. The decline in competition is so plain that even centrist organizations like The Economist and the Brookings Institution have

The last forty years have seen a transformation in American business. Three major airlines dominate the skies. About ten pharmaceutical companies make up the lion’s share of the industry. Three major companies constitute the seed and pesticide industry. And 70 percent of beer is sold to one of two conglomerates. Scholars have shown that this wave of consolidation has depressed wages, increased inequality, and arrested small business formation. The decline in competition is so plain that even centrist organizations like The Economist and the Brookings Institution have  Much has been written about the courageous rebuilding of the Iraqi libraries destroyed by the Islamic State during its occupation of Mosul and other cities in the region. In adjacent Kurdish Iraq, the centuries-old struggle to build a repository of Kurdish culture and history has primarily and often necessarily continued with little visibility or fanfare, undertaken by willful idealists and brave individualists. Recently, I visited Zheen Archive Center, and met the people making that dream a reality. Here, two optimistic, broadminded brothers and an all-women team of crack manuscript preservationists are building a collection of books, manuscripts, and papers that have survived hundreds of years of language bans and the mass destruction of property that accompanied the countless murders of Saddam Hussein’s 1980s genocidal campaign, Anfal. Zheen—which means “life” in the Sorani dialect of Kurdish—houses the greatest collection of Kurdish cultural material of any other institution in the four contemporary nation-states that comprise the region of the Kurds, and probably the world. Remarkably, the Salih brothers formally founded Zheen in just 2004, and only acquired their present location, the nondescript four-story office building that houses its archives in northwest Sulaimani, in 2009.

Much has been written about the courageous rebuilding of the Iraqi libraries destroyed by the Islamic State during its occupation of Mosul and other cities in the region. In adjacent Kurdish Iraq, the centuries-old struggle to build a repository of Kurdish culture and history has primarily and often necessarily continued with little visibility or fanfare, undertaken by willful idealists and brave individualists. Recently, I visited Zheen Archive Center, and met the people making that dream a reality. Here, two optimistic, broadminded brothers and an all-women team of crack manuscript preservationists are building a collection of books, manuscripts, and papers that have survived hundreds of years of language bans and the mass destruction of property that accompanied the countless murders of Saddam Hussein’s 1980s genocidal campaign, Anfal. Zheen—which means “life” in the Sorani dialect of Kurdish—houses the greatest collection of Kurdish cultural material of any other institution in the four contemporary nation-states that comprise the region of the Kurds, and probably the world. Remarkably, the Salih brothers formally founded Zheen in just 2004, and only acquired their present location, the nondescript four-story office building that houses its archives in northwest Sulaimani, in 2009. No story captures the lonely act of naming as a truly human capacity better than Daniel Defoe’s novel Robinson Crusoe (1719), where it saves the shipwrecked Crusoe from disintegration. Here, the logic of naming acquires a new twist. Friday—not an animal, but an aboriginal from a nearby island—becomes the center of his universe, the saving grace of his dwindling powers of perception, the focal point in his attempts to restructure something that at least looks like a society. Friday is not particularly responsive. But Crusoe invents a whole new kind of mastery, one in which Friday, in fact, becomes wholly redundant. Crusoe does not need Friday to confirm his powers. He does not need such affirmation because he has invented the technology of naming. Friday is named after a day in the calendar, and not according to a higher principle. He is named according to a certain principle of contingency, an operation of chance that can be repeated, serially, in as many varieties and forms as one likes. The question is no longer if names come from God or not, but rather how we are to produce them in the most efficient manner possible.

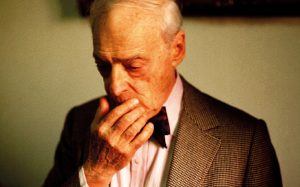

No story captures the lonely act of naming as a truly human capacity better than Daniel Defoe’s novel Robinson Crusoe (1719), where it saves the shipwrecked Crusoe from disintegration. Here, the logic of naming acquires a new twist. Friday—not an animal, but an aboriginal from a nearby island—becomes the center of his universe, the saving grace of his dwindling powers of perception, the focal point in his attempts to restructure something that at least looks like a society. Friday is not particularly responsive. But Crusoe invents a whole new kind of mastery, one in which Friday, in fact, becomes wholly redundant. Crusoe does not need Friday to confirm his powers. He does not need such affirmation because he has invented the technology of naming. Friday is named after a day in the calendar, and not according to a higher principle. He is named according to a certain principle of contingency, an operation of chance that can be repeated, serially, in as many varieties and forms as one likes. The question is no longer if names come from God or not, but rather how we are to produce them in the most efficient manner possible. Is this a good moment – propitious, welcoming – for the appearance of a long, rich and unflaggingly detailed account of the later life of Saul Bellow? Ten years in the making, Zachary Leader’s biography was rubber-stamped at an earlier and distinctively different point in time. Then, the writer still reflected the glow of adulation – from the reviews of James Atlas’s single-volume biography Bellow(2000); his final novel Ravelstein (2000) and his Collected Stories (2001); from the 50th-anniversary tributes to The Adventures of Augie March in 2003 and the appearance, the same year, of the Library of America compendium, Novels 1944-1953; and from the obituaries and memorial essays that appeared on his death in 2005, aged 89. When, around that time, I starting getting interested in fiction, I was made to feel about Bellow’s writing more or less what Charlie Citrine, in Humboldt’s Gift (1975), recalls feeling about Leon Trotsky in the 1930s – that if I didn’t read him at once, I wouldn’t be worth conversing with.

Is this a good moment – propitious, welcoming – for the appearance of a long, rich and unflaggingly detailed account of the later life of Saul Bellow? Ten years in the making, Zachary Leader’s biography was rubber-stamped at an earlier and distinctively different point in time. Then, the writer still reflected the glow of adulation – from the reviews of James Atlas’s single-volume biography Bellow(2000); his final novel Ravelstein (2000) and his Collected Stories (2001); from the 50th-anniversary tributes to The Adventures of Augie March in 2003 and the appearance, the same year, of the Library of America compendium, Novels 1944-1953; and from the obituaries and memorial essays that appeared on his death in 2005, aged 89. When, around that time, I starting getting interested in fiction, I was made to feel about Bellow’s writing more or less what Charlie Citrine, in Humboldt’s Gift (1975), recalls feeling about Leon Trotsky in the 1930s – that if I didn’t read him at once, I wouldn’t be worth conversing with. “I was a human first, and then I learned to be a

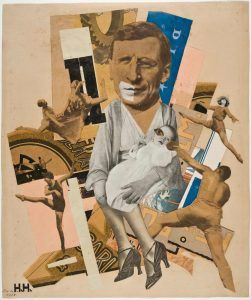

“I was a human first, and then I learned to be a  In 1919 the German Dada artist Raoul Hausmann dismissed marriage as “the projection of rape into law”. It’s a statement that relishes its own violence: he is limbering up to fight marriage to the death. A strange mixture of dandy, wild man, provocateur and social engineer, Hausmann believed that the socialist revolution the Dadaists sought couldn’t be attained without a corresponding sexual revolution. And he lived as he preached. He was married, but was also in a four-year relationship with fellow artist

In 1919 the German Dada artist Raoul Hausmann dismissed marriage as “the projection of rape into law”. It’s a statement that relishes its own violence: he is limbering up to fight marriage to the death. A strange mixture of dandy, wild man, provocateur and social engineer, Hausmann believed that the socialist revolution the Dadaists sought couldn’t be attained without a corresponding sexual revolution. And he lived as he preached. He was married, but was also in a four-year relationship with fellow artist  Last November, on the Monday before Thanksgiving, David* was sitting in traffic on his drive home from work. He was suddenly overwhelmed by the realization that everything he experienced was filtered through his brain, entirely subjective, and possibly a complete fabrication.

Last November, on the Monday before Thanksgiving, David* was sitting in traffic on his drive home from work. He was suddenly overwhelmed by the realization that everything he experienced was filtered through his brain, entirely subjective, and possibly a complete fabrication. Music can intensify moments of elation and moments of despair. It can connect people and it can divide them. The prospect of psychologists turning their lens on music might give a person the heebie-jeebies, however, conjuring up an image of humorless people in white lab coats manipulating sequences of beeps and boops to make grand pronouncements about human musicality.

Music can intensify moments of elation and moments of despair. It can connect people and it can divide them. The prospect of psychologists turning their lens on music might give a person the heebie-jeebies, however, conjuring up an image of humorless people in white lab coats manipulating sequences of beeps and boops to make grand pronouncements about human musicality. I was born in Hamburg, Germany, in 1949, so I grew up playing cowboys and Indians with my cousins in the rubble fields of my native city. Family lore had it that my mother, who had survived the Hamburg firestorm of 1943, made me baby shirts from the sugar bags that came in American care packages. Her father had been sent to a concentration camp during the early days of the Nazi dictatorship because he collected dues for an illegal union; fortunately, he survived. Because of the housing shortage caused by the bombings, my parents and I, for the first 11 years of my life, lived in a one-room apartment. Suffice it to say my childhood was a daily reminder of the catastrophic consequences of the destruction of the Weimar democracy and the rise of Adolf Hitler.

I was born in Hamburg, Germany, in 1949, so I grew up playing cowboys and Indians with my cousins in the rubble fields of my native city. Family lore had it that my mother, who had survived the Hamburg firestorm of 1943, made me baby shirts from the sugar bags that came in American care packages. Her father had been sent to a concentration camp during the early days of the Nazi dictatorship because he collected dues for an illegal union; fortunately, he survived. Because of the housing shortage caused by the bombings, my parents and I, for the first 11 years of my life, lived in a one-room apartment. Suffice it to say my childhood was a daily reminder of the catastrophic consequences of the destruction of the Weimar democracy and the rise of Adolf Hitler. The pyramids and the Great Sphinx

The pyramids and the Great Sphinx

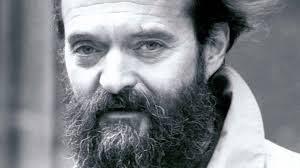

Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) is one of those fortunate composers who has created his own world in music—and is beloved for it in his lifetime. The Estonian, who for the last decade has been the world’s most performed living composer, started his career writing neoclassical pieces influenced by the Russian greats, chiefly Prokofiev and Shostakovich. Then he discovered Schoenberg’s twelve-tone scale, serialism, and other twentieth-century experimental techniques and soon became a prominent member of the avant-garde. But Soviet censors disapproved, and in the late 1960s their unofficial censorship removed Pärt’s music from concert programs and sent him into what he called a “period of contemplative silence.”

Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) is one of those fortunate composers who has created his own world in music—and is beloved for it in his lifetime. The Estonian, who for the last decade has been the world’s most performed living composer, started his career writing neoclassical pieces influenced by the Russian greats, chiefly Prokofiev and Shostakovich. Then he discovered Schoenberg’s twelve-tone scale, serialism, and other twentieth-century experimental techniques and soon became a prominent member of the avant-garde. But Soviet censors disapproved, and in the late 1960s their unofficial censorship removed Pärt’s music from concert programs and sent him into what he called a “period of contemplative silence.” But it wasn’t as if, by leaving church, I could escape. In the Midwest, everything is haunted by Jesus: the Rust Belt towns, the long gray freeways; county fairs in the summer with headlining Christian bands; breweries full of wholesome Christian hipsters in warm sweaters, Iron and Wine or Sufjan Stevens on the sound system. After belief, I didn’t want to drive through the suburbs and come upon some postwar church with hymnals full of

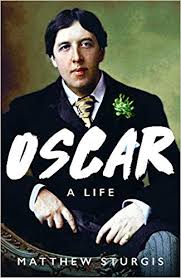

But it wasn’t as if, by leaving church, I could escape. In the Midwest, everything is haunted by Jesus: the Rust Belt towns, the long gray freeways; county fairs in the summer with headlining Christian bands; breweries full of wholesome Christian hipsters in warm sweaters, Iron and Wine or Sufjan Stevens on the sound system. After belief, I didn’t want to drive through the suburbs and come upon some postwar church with hymnals full of  Each critic sees him- or herself in Oscar Wilde. Saint Oscar; Wilde the Irishman; Wilde the wit. The classicist; the socialist; the martyr for gay rights. “To be premature is to be perfect”, Wilde wrote; “History lives through its anachronisms.” It is in large part on this quality that the Wilde industry has been built. For an industry it certainly is. Books on Wilde are glamorous in a way that academic monographs seldom are. They come with beautiful artwork and endorsements by Stephen Fry. They lend themselves to the crossover market, eminently desirable to publishers as monograph sales dwindle. At their zenith, they beget publicity tours and a spot on a Waterstones table. In a world where most of us academics regularly spend weeks preparing a conference paper to deliver before an audience of a dozen, this is stardom.

Each critic sees him- or herself in Oscar Wilde. Saint Oscar; Wilde the Irishman; Wilde the wit. The classicist; the socialist; the martyr for gay rights. “To be premature is to be perfect”, Wilde wrote; “History lives through its anachronisms.” It is in large part on this quality that the Wilde industry has been built. For an industry it certainly is. Books on Wilde are glamorous in a way that academic monographs seldom are. They come with beautiful artwork and endorsements by Stephen Fry. They lend themselves to the crossover market, eminently desirable to publishers as monograph sales dwindle. At their zenith, they beget publicity tours and a spot on a Waterstones table. In a world where most of us academics regularly spend weeks preparing a conference paper to deliver before an audience of a dozen, this is stardom.