Sarah Manavis in New Statesman:

Cultural Marxism is a theory that started in the early 20th century, which was popularised in the aftermath of the socialist revolution (this great piece in the Guardian explains it in depth). The idea was that Marxism should extend beyond class and into cultural equality and that, through major institutions like schools and the media, cultural values could progressively be changed. The theory was later adopted by the philosophers at the Frankfurt School who posited that the only way to destroy capitalism was to destroy it in all walks of life; where, not just classes, but all genders, races, and religions could live in society equally.

Cultural Marxism is a theory that started in the early 20th century, which was popularised in the aftermath of the socialist revolution (this great piece in the Guardian explains it in depth). The idea was that Marxism should extend beyond class and into cultural equality and that, through major institutions like schools and the media, cultural values could progressively be changed. The theory was later adopted by the philosophers at the Frankfurt School who posited that the only way to destroy capitalism was to destroy it in all walks of life; where, not just classes, but all genders, races, and religions could live in society equally.

While this may seem unimportant, the Frankfurt School’s adoption of – and modifications to – cultural Marxism is where the conspiracy theory truly begins. The Frankfurt School’s predominantly Jewish members of the school were forced to flee to America by the Nazis in the 1940s, where many went on to teach, write, and commentate in mainstream institutions. This, conspiracy theorists claim, is when cultural Marxists began to poison the West – and when cultural Marxists began their attempts to undermine its values.

More here.

“

“

On 6 January, 2011, the world watched aghast as sections of Pakistan’s modern legal fraternity took to the streets of the country’s capital, Islamabad, to shower petals on the self-confessed killer,

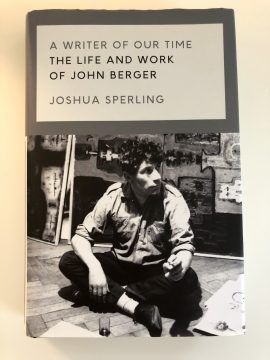

On 6 January, 2011, the world watched aghast as sections of Pakistan’s modern legal fraternity took to the streets of the country’s capital, Islamabad, to shower petals on the self-confessed killer,  As early as the mid-1950s, the art critic

As early as the mid-1950s, the art critic  When was the last time you heard a seminar speaker claim there was ‘no difference’ between two groups because the difference was ‘statistically non-significant’?

When was the last time you heard a seminar speaker claim there was ‘no difference’ between two groups because the difference was ‘statistically non-significant’? There is a wonderful metaphor in Alastair Macintyre’s After Virtue, in which the philosopher asks us to imagine a world hit by some terrible calamity that caused scientific and technical knowledge to be almost destroyed. What was left was smashed into thousands upon thousands of disconnected pieces, and the inhabitants of this world had to piece together their understanding of science and technology from what was lost, trying to line up the remnants of the earlier age as best they could.

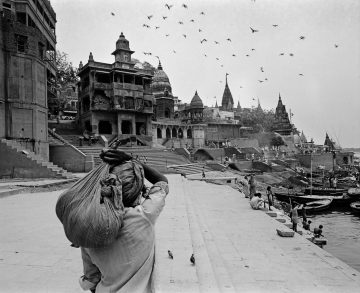

There is a wonderful metaphor in Alastair Macintyre’s After Virtue, in which the philosopher asks us to imagine a world hit by some terrible calamity that caused scientific and technical knowledge to be almost destroyed. What was left was smashed into thousands upon thousands of disconnected pieces, and the inhabitants of this world had to piece together their understanding of science and technology from what was lost, trying to line up the remnants of the earlier age as best they could. The Twice-Born,” a new memoir by Aatish Taseer, is troubled by a single plaintive question: Does a city steeped in tradition have a future in modern India? The setting is Benares, the spiritual capital of Hinduism, where more than five million pilgrims flock each year to worship, bathe, and burn their dead. Dying while in Benares, it is said, will release a Hindu from the cycle of reincarnation, and Taseer discovers an industry of death that’s alive and well in the city. He describes corpses that “sizzled away on funeral pyres,” as dinghies drifted on the Ganges amid smoke and marigolds. Taseer, to be clear, has not come to Benares to die. He’s in his thirties for most of the memoir, and, anyway, he’s not religious. His pilgrimage is secular; he seeks to filter the contradictions of present-day India through his life story. In the process, “

The Twice-Born,” a new memoir by Aatish Taseer, is troubled by a single plaintive question: Does a city steeped in tradition have a future in modern India? The setting is Benares, the spiritual capital of Hinduism, where more than five million pilgrims flock each year to worship, bathe, and burn their dead. Dying while in Benares, it is said, will release a Hindu from the cycle of reincarnation, and Taseer discovers an industry of death that’s alive and well in the city. He describes corpses that “sizzled away on funeral pyres,” as dinghies drifted on the Ganges amid smoke and marigolds. Taseer, to be clear, has not come to Benares to die. He’s in his thirties for most of the memoir, and, anyway, he’s not religious. His pilgrimage is secular; he seeks to filter the contradictions of present-day India through his life story. In the process, “ For all their pontificating and complex moral theories, ethicists are just as disappointingly flawed as the rest of humanity. A study of 417 professors

For all their pontificating and complex moral theories, ethicists are just as disappointingly flawed as the rest of humanity. A study of 417 professors  Imagine your response to picking up a copy of the leading scientific journal Nature and reading the headline: “The myth that evolution applies to humans.” Anyone even vaguely familiar with the advances in neuroscience over the past 15–20 years regarding sex influences on brain function might have a similar response to a recent headline in Nature: “

Imagine your response to picking up a copy of the leading scientific journal Nature and reading the headline: “The myth that evolution applies to humans.” Anyone even vaguely familiar with the advances in neuroscience over the past 15–20 years regarding sex influences on brain function might have a similar response to a recent headline in Nature: “ Boeing executives are offering a simple explanation for why the company’s best-selling plane in the world, the 737 MAX 8, crashed twice in the past several months, leaving Jakarta, Indonesia, in October and then Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in March. Executives claimed Wednesday, March 27, that the cause was a software problem — and that a new software upgrade fixes it.

Boeing executives are offering a simple explanation for why the company’s best-selling plane in the world, the 737 MAX 8, crashed twice in the past several months, leaving Jakarta, Indonesia, in October and then Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in March. Executives claimed Wednesday, March 27, that the cause was a software problem — and that a new software upgrade fixes it. In 1886, Clark B

In 1886, Clark B Something is happening in African literature: The women are coming. For decades now, a river of original and important writing by female authors has been flowing out of that continent — books by writers such as Marlene van Niekerk, of whose second novel Liesl Schillinger wrote in these pages, “books like ‘Agaat’ … are the reason people read novels”; Tsitsi Dangarembga (“Nervous Conditions”); and, of course, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Now that river has burst its banks and become a flood. Namwali Serpell’s extraordinary, ambitious, evocative first novel, “The Old Drift,” contributes powerfully to this new wave.

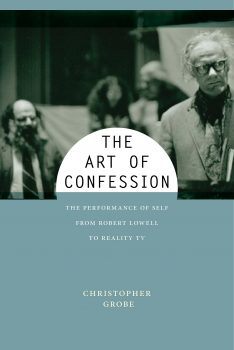

Something is happening in African literature: The women are coming. For decades now, a river of original and important writing by female authors has been flowing out of that continent — books by writers such as Marlene van Niekerk, of whose second novel Liesl Schillinger wrote in these pages, “books like ‘Agaat’ … are the reason people read novels”; Tsitsi Dangarembga (“Nervous Conditions”); and, of course, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Now that river has burst its banks and become a flood. Namwali Serpell’s extraordinary, ambitious, evocative first novel, “The Old Drift,” contributes powerfully to this new wave. Is confessional poetry still interesting in our age of oversharing? Is it even confessional? If my students are any indication, readers immersed in multiple platforms of never-ending self-disclosure might not find the poetry of Robert Lowell or Anne Sexton particularly exhibitionist. Lowell’s Life Studies is personal, certainly, but not nearly as personal as your average Instagram story, not as revealing as the anecdotes my students are apt to volunteer in and after class, maybe not as real as the Real Housewives. Lowell famously described his turn toward the personal as a movement away from a rarefied and bloodless commitment to craft, “a breakthrough back into life” that promised to reenergize the writers of an entire generation. A half-century on, the subversions of their self-exposure can be harder to recognize. In the full thrall of TMI, it might be that the strangeness of confessional poetry has more to do these days with its being poetry than its being confessional. This development is not necessarily a bad thing. Indeed, I often try to highlight something like this dynamic by playing for my classes a recording of Sylvia Plath reading “Daddy” a few months before her death. It is an electrifying performance that completely reconfigures the way my students approach her poems. Plath brings to the text a theatrical intensity far flung from the rhetoric of therapeutic unburdening that the “confessional” label seems to suggest. As Plath declaims it, “Daddy” sounds more like the soliloquy of an Elizabethan villain than a straightforward exercise in self-expression. It is not so clear that such words unearth any sort of inner truth about the speaker, but they are certainly dramatic.

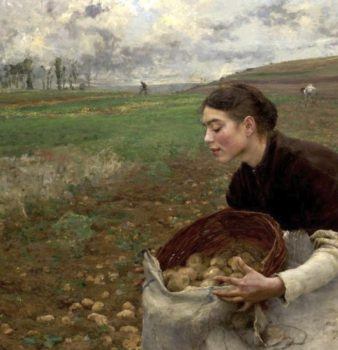

Is confessional poetry still interesting in our age of oversharing? Is it even confessional? If my students are any indication, readers immersed in multiple platforms of never-ending self-disclosure might not find the poetry of Robert Lowell or Anne Sexton particularly exhibitionist. Lowell’s Life Studies is personal, certainly, but not nearly as personal as your average Instagram story, not as revealing as the anecdotes my students are apt to volunteer in and after class, maybe not as real as the Real Housewives. Lowell famously described his turn toward the personal as a movement away from a rarefied and bloodless commitment to craft, “a breakthrough back into life” that promised to reenergize the writers of an entire generation. A half-century on, the subversions of their self-exposure can be harder to recognize. In the full thrall of TMI, it might be that the strangeness of confessional poetry has more to do these days with its being poetry than its being confessional. This development is not necessarily a bad thing. Indeed, I often try to highlight something like this dynamic by playing for my classes a recording of Sylvia Plath reading “Daddy” a few months before her death. It is an electrifying performance that completely reconfigures the way my students approach her poems. Plath brings to the text a theatrical intensity far flung from the rhetoric of therapeutic unburdening that the “confessional” label seems to suggest. As Plath declaims it, “Daddy” sounds more like the soliloquy of an Elizabethan villain than a straightforward exercise in self-expression. It is not so clear that such words unearth any sort of inner truth about the speaker, but they are certainly dramatic. All 4,500 named varieties of potatoes trace their ancestry to the Americas. Wild potatoes grow along the American cordillera, the mountains that run from the Andes to Alaska. People living on its slopes have been eating potatoes for time out of mind. Stone tools and preserved potato peels show that wild potatoes were being prepared for food in southern Utah and south-central Chile nearly 13,000 years ago; similar evidence dates their domestication from at least 7800 BCE on the northern coast of Peru. They formed an important part of the diet of many of the cultures inhabiting the 9000 kilometers between Utah and Chile.

All 4,500 named varieties of potatoes trace their ancestry to the Americas. Wild potatoes grow along the American cordillera, the mountains that run from the Andes to Alaska. People living on its slopes have been eating potatoes for time out of mind. Stone tools and preserved potato peels show that wild potatoes were being prepared for food in southern Utah and south-central Chile nearly 13,000 years ago; similar evidence dates their domestication from at least 7800 BCE on the northern coast of Peru. They formed an important part of the diet of many of the cultures inhabiting the 9000 kilometers between Utah and Chile.