Ty Joplin in Albawaba:

Jihadi violence ebbs and flows, with groups rising and falling in prominence as they gain and lose followers and legitimacy. Al Qaeda, once the premium jihadi brand that local groups scrambled to associate with, was made to look stale and outdated by the explosive rise of ISIS. As ISIS fades, many around the world are holding their breath for the next global terror group.

Jihadi violence ebbs and flows, with groups rising and falling in prominence as they gain and lose followers and legitimacy. Al Qaeda, once the premium jihadi brand that local groups scrambled to associate with, was made to look stale and outdated by the explosive rise of ISIS. As ISIS fades, many around the world are holding their breath for the next global terror group.

But some Indonesian families have associated themselves with radical extremism for decades, spanning generations.

Inside the terror networks of Indonesia, a global lesson is laid bare; that even though particular manifestations of violent jihad come in waves, the ideology can remain firmly entrenched. Indonesia’s long history of radical violence and of families fostering extremist sentiments can serve as a blueprint to understand how jihadism remains resilient, and how it can be combated at its core.

More here.

Turkey is entering a new era. Following a failed military coup against President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in 2016, a referendum last April

Turkey is entering a new era. Following a failed military coup against President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in 2016, a referendum last April  A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway

A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway

There is a dial in front of you, and if you turn it, a stranger who is in mild pain from being shocked will experience a tiny increase in the amount of the shock, so slight that he doesn’t even notice it. You turn it and leave. And then hundreds of people go up to the dial and each also turns it, so that eventually the victim is screaming in agony.

There is a dial in front of you, and if you turn it, a stranger who is in mild pain from being shocked will experience a tiny increase in the amount of the shock, so slight that he doesn’t even notice it. You turn it and leave. And then hundreds of people go up to the dial and each also turns it, so that eventually the victim is screaming in agony. As

As  ‘The Divine Comedy is a book that everyone ought to read,’ according to Jorge Luis Borges, and every Italian has read it. Dante’s midlife crisis in the dark wood, his journey down the circles of hell, up the ledges of Purgatory and into the arms of Beatrice is mother’s milk to Italian schoolchildren. Today lines from La divina commediaare printed on T-shirts; before the war, as Primo Levi recalled, there were ‘Dante tournaments’ on the streets of Turin, where one boy would recite the start of a canto and his rival would try to complete it. I had two Italian students in an English literature seminar last year who sniggered when I mentioned the once standard Penguin translation of the Comedy by Dorothy L. Sayers, inventor of the Dante-loving Lord Peter Wimsey. ‘Dante in translation,’ they explained, ‘isn’t the real Dante.’ But, as Ian Thomson shows, the real Dante is hard to find even in Italian. Over 800 pre-Gutenberg editions of La divina commedia are known to exist, most marred by errors and nibbled by rats, but because none is in Dante’s hand we can’t be sure what he actually wrote. An example of the way his poem was doctored by the copiers can be seen by the fact that it was Boccaccio (author of The Decameron and Dante’s first biographer) who added the divina to what Dante had simply called La commedia.

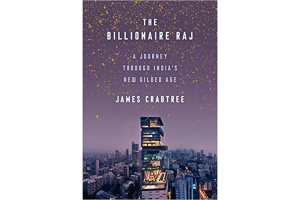

‘The Divine Comedy is a book that everyone ought to read,’ according to Jorge Luis Borges, and every Italian has read it. Dante’s midlife crisis in the dark wood, his journey down the circles of hell, up the ledges of Purgatory and into the arms of Beatrice is mother’s milk to Italian schoolchildren. Today lines from La divina commediaare printed on T-shirts; before the war, as Primo Levi recalled, there were ‘Dante tournaments’ on the streets of Turin, where one boy would recite the start of a canto and his rival would try to complete it. I had two Italian students in an English literature seminar last year who sniggered when I mentioned the once standard Penguin translation of the Comedy by Dorothy L. Sayers, inventor of the Dante-loving Lord Peter Wimsey. ‘Dante in translation,’ they explained, ‘isn’t the real Dante.’ But, as Ian Thomson shows, the real Dante is hard to find even in Italian. Over 800 pre-Gutenberg editions of La divina commedia are known to exist, most marred by errors and nibbled by rats, but because none is in Dante’s hand we can’t be sure what he actually wrote. An example of the way his poem was doctored by the copiers can be seen by the fact that it was Boccaccio (author of The Decameron and Dante’s first biographer) who added the divina to what Dante had simply called La commedia. James Crabtree’s The Billionaire Raj: A Journey Through India’s New Gilded Age devotes the bulk of its length to the new cadre of super-rich that has arisen in India’s newly resurgent economy, but it opens with an important point: India is still an intensely poor country. The average citizen earns less than $2,000 a year, and the low-end of what constitutes the richest one percent of the country is only around $33,000. The richest one percent of the country owns more than half the nation’s wealth; it’s a starker income disparity than virtually any other country on Earth.

James Crabtree’s The Billionaire Raj: A Journey Through India’s New Gilded Age devotes the bulk of its length to the new cadre of super-rich that has arisen in India’s newly resurgent economy, but it opens with an important point: India is still an intensely poor country. The average citizen earns less than $2,000 a year, and the low-end of what constitutes the richest one percent of the country is only around $33,000. The richest one percent of the country owns more than half the nation’s wealth; it’s a starker income disparity than virtually any other country on Earth. In his new book, In Defense of Public Lands: The Case against Privatization and Transfer (Temple University Press), Steven Davis, political science professor at Edgewood College in Madison, Wisconsin, takes on the “privatizers.” His book is an even-handed and thorough look at public lands in the United States. Although public support for wilderness, national parks, and other public lands

In his new book, In Defense of Public Lands: The Case against Privatization and Transfer (Temple University Press), Steven Davis, political science professor at Edgewood College in Madison, Wisconsin, takes on the “privatizers.” His book is an even-handed and thorough look at public lands in the United States. Although public support for wilderness, national parks, and other public lands  Cordelia Fine in the Financial Times:

Cordelia Fine in the Financial Times: Richard V Reeves at Aeon:

Richard V Reeves at Aeon: Eric Levitz in NY Magazine [h/t: Leonard Benardo]:

Eric Levitz in NY Magazine [h/t: Leonard Benardo]: A common argument against Bergman is that he is fated for oblivion because his movies did not advance the art of film; they were

A common argument against Bergman is that he is fated for oblivion because his movies did not advance the art of film; they were