Mark Hay in Atlas Obscura:

ZAHIR AL-DIN MUHAMMAD, THE 16TH century Central Asian prince better known as Babur, is renowned for his fierce pedigree and proclivities. Descended from both Timur and Genghis Khan, he used military genius to overcome strife and exile, conquer northern India, and found the Moghul dynasty, which endured for over 300 years. He was a warlord who built towers of his enemies’ skulls on at least four occasions. Yet he was also a cultured man who wrote tomes on law and Sufi philosophy, collections of poetry, and a shockingly honest memoir, the Baburnama, in which he appears to us as one of the most complex and human figures of the early modern era.

ZAHIR AL-DIN MUHAMMAD, THE 16TH century Central Asian prince better known as Babur, is renowned for his fierce pedigree and proclivities. Descended from both Timur and Genghis Khan, he used military genius to overcome strife and exile, conquer northern India, and found the Moghul dynasty, which endured for over 300 years. He was a warlord who built towers of his enemies’ skulls on at least four occasions. Yet he was also a cultured man who wrote tomes on law and Sufi philosophy, collections of poetry, and a shockingly honest memoir, the Baburnama, in which he appears to us as one of the most complex and human figures of the early modern era.

Through the Baburnama, we learn that Babur was versed in courtly Persian speech and custom, yet nonetheless a populist who built strong ties with nomads and championed the vernacular Chagatai Turkic tongue in the arts. He was a pious man, but was also given to libertine escapades, including massive, wine-fueled parties.

But the first—and arguably one of the most culturally consequential—personal details he reveals is that he was a food snob.

More here. [Thanks to Farrukh Azfar.]

Far from just being the product of our parents, University of Adelaide scientists have shown that widespread transfer of genes between species has radically changed the genomes of today’s mammals, and been an important driver of evolution.

Far from just being the product of our parents, University of Adelaide scientists have shown that widespread transfer of genes between species has radically changed the genomes of today’s mammals, and been an important driver of evolution. A seasonal

A seasonal Why do wealthy societies spend good money on projects such as this? Higgs bosons and images from the Voyager spacecraft don’t do anything useful and don’t make any of us richer, as Radford acknowledges, though he has no time for such philistinism. His heart and his mind are with the Roman thinker

Why do wealthy societies spend good money on projects such as this? Higgs bosons and images from the Voyager spacecraft don’t do anything useful and don’t make any of us richer, as Radford acknowledges, though he has no time for such philistinism. His heart and his mind are with the Roman thinker  Gossip, speculation, and longing—and the discomfort (and occasional pleasure) of perpetual doubt—are the grounds on which contemporary queer men and women have become used to constructing our genealogies. We possess historical facts enough to fantasize about our “great-grandparents”: the evasive extravagance of Oscar Wilde; the repression with which E.M. Forster asks us to “only connect”; the ambiguity in Djuna Barnes’s famous claim, “I am not a lesbian, I just loved Thelma”; or the half-missing archive of Emma Goldman’s correspondence with women. The following generation of gay men was decimated by a plague, meaning that 30- to 50-year-old gay men will be the first generation to be both openly gay and alive. Even if it is easier now to imagine a queer family of brothers and sisters, it remains much more difficult to imagine a queer lineage. We long for a family tree that never quite appears in full: for queer mothers and fathers that could somehow supplement (or replace) the biological ones whose lives differ so greatly from our own. We construct these families through gossip and speculation, staring at chapter breaks and ellipses until they give us that aunt we might have had. Looking hard enough, we hope, we all might have that aunt.

Gossip, speculation, and longing—and the discomfort (and occasional pleasure) of perpetual doubt—are the grounds on which contemporary queer men and women have become used to constructing our genealogies. We possess historical facts enough to fantasize about our “great-grandparents”: the evasive extravagance of Oscar Wilde; the repression with which E.M. Forster asks us to “only connect”; the ambiguity in Djuna Barnes’s famous claim, “I am not a lesbian, I just loved Thelma”; or the half-missing archive of Emma Goldman’s correspondence with women. The following generation of gay men was decimated by a plague, meaning that 30- to 50-year-old gay men will be the first generation to be both openly gay and alive. Even if it is easier now to imagine a queer family of brothers and sisters, it remains much more difficult to imagine a queer lineage. We long for a family tree that never quite appears in full: for queer mothers and fathers that could somehow supplement (or replace) the biological ones whose lives differ so greatly from our own. We construct these families through gossip and speculation, staring at chapter breaks and ellipses until they give us that aunt we might have had. Looking hard enough, we hope, we all might have that aunt. Hopkins is the laureate of “all things counter, original, spare, strange”. He is also, to my mind, the most exquisite English poet of the 19th century. In life, however, he felt the censure not only of his strict Catholicism but also of his own isolation. In one of his late sonnets, he summed up his position as an unpublished – and perhaps unpublishable – poet. A reader unfamiliar with Hopkins’s work will feel immediately the taut difficulty of his language, the force of his sound-scapes, and the miraculous effect of his anthimeria, as in his striking use of “began” as a noun:

Hopkins is the laureate of “all things counter, original, spare, strange”. He is also, to my mind, the most exquisite English poet of the 19th century. In life, however, he felt the censure not only of his strict Catholicism but also of his own isolation. In one of his late sonnets, he summed up his position as an unpublished – and perhaps unpublishable – poet. A reader unfamiliar with Hopkins’s work will feel immediately the taut difficulty of his language, the force of his sound-scapes, and the miraculous effect of his anthimeria, as in his striking use of “began” as a noun: A killer stalks the American street. Its weaponry is subtle, but it is responsible for the demolition of countless lives, and the damage of many communities. After it sneaks into a home, it creates social pathology and helps harvest political cruelty. It is loneliness. The United States of America has created a culture of solitary struggle and isolation. It should not shock too many careful observers who consider the predictable consequences of building an entire civilization on the mud and sewage of cutthroat, competitive corporate capitalism. The true meaning of icy bromides like, “rugged individualism,” “pull yourself up by your bootstraps,” and “no free lunch,” is not a celebration of individual freedom as much as it is a “you’re on your own” ethic, or lack thereof, resulting in communal fissure and political friction.

A killer stalks the American street. Its weaponry is subtle, but it is responsible for the demolition of countless lives, and the damage of many communities. After it sneaks into a home, it creates social pathology and helps harvest political cruelty. It is loneliness. The United States of America has created a culture of solitary struggle and isolation. It should not shock too many careful observers who consider the predictable consequences of building an entire civilization on the mud and sewage of cutthroat, competitive corporate capitalism. The true meaning of icy bromides like, “rugged individualism,” “pull yourself up by your bootstraps,” and “no free lunch,” is not a celebration of individual freedom as much as it is a “you’re on your own” ethic, or lack thereof, resulting in communal fissure and political friction. Being a

Being a  Socrates died by drinking hemlock, condemned to death by the people of Athens. Albert Camus met his end in a car that wrapped itself around a tree at high speed. Nietzsche collapsed into insanity after weeping over a beaten horse. Posterity loves a tragic end, which is one reason why the cult of David Hume, arguably the greatest philosopher the West has ever produced, never took off.

Socrates died by drinking hemlock, condemned to death by the people of Athens. Albert Camus met his end in a car that wrapped itself around a tree at high speed. Nietzsche collapsed into insanity after weeping over a beaten horse. Posterity loves a tragic end, which is one reason why the cult of David Hume, arguably the greatest philosopher the West has ever produced, never took off. In 1837, Charles Darwin sketched a spindly tree of life in one of his notebooks. Its stick-figure trunk sprouted into four sets of branches. The drawing illustrated his radical idea that, over time, organisms change to give rise to new species.

In 1837, Charles Darwin sketched a spindly tree of life in one of his notebooks. Its stick-figure trunk sprouted into four sets of branches. The drawing illustrated his radical idea that, over time, organisms change to give rise to new species. Freedom is the ability to pursue the life one values. This view of freedom is inclusive, open-ended, and flexible. It embraces our plural, evolving, and diverse conceptions of the good life. It also admits other long-standing ideas of freedom, such as not being held in servitude, possessing political self-rule, or enjoying the right to act, speak, and think as one desires.

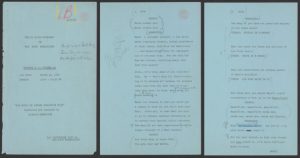

Freedom is the ability to pursue the life one values. This view of freedom is inclusive, open-ended, and flexible. It embraces our plural, evolving, and diverse conceptions of the good life. It also admits other long-standing ideas of freedom, such as not being held in servitude, possessing political self-rule, or enjoying the right to act, speak, and think as one desires. As the nineteenth century came to an end, rumours started to circulate widely about the violence perpetrated by the regime of King Leopold II in the Congo Free State. Parliamentary intervention followed from involvement by the two main NGOs: the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society and the Aborigines Protection Society. In 1903, a question was asked in the House of Commons by the Liberal MP Herbert Samuel. The foreign secretary, Lord Lansdowne, ordered the British consul and his man on the spot, Roger Casement, to journey into the upper Congo. Having spent five years reporting officially on many aspects of Leopold’s colonial administration, Casement was well-placed to investigate the stories. He would spend the next three months travelling through the region. On exiting the river with a dossier of hand-written reports, copied correspondences and memos, testimonies and a diary, he scribbled the first of nearly three hundred letters to ED Morel, a young activist-writer. He recommended him to read Heart of Darkness and suggested he contact the author, Joseph Conrad, to see if he would support a public campaign for systemic reform. Casement and Conrad had met in the lower Congo in 1890 and a friendship had developed between the two men.

As the nineteenth century came to an end, rumours started to circulate widely about the violence perpetrated by the regime of King Leopold II in the Congo Free State. Parliamentary intervention followed from involvement by the two main NGOs: the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society and the Aborigines Protection Society. In 1903, a question was asked in the House of Commons by the Liberal MP Herbert Samuel. The foreign secretary, Lord Lansdowne, ordered the British consul and his man on the spot, Roger Casement, to journey into the upper Congo. Having spent five years reporting officially on many aspects of Leopold’s colonial administration, Casement was well-placed to investigate the stories. He would spend the next three months travelling through the region. On exiting the river with a dossier of hand-written reports, copied correspondences and memos, testimonies and a diary, he scribbled the first of nearly three hundred letters to ED Morel, a young activist-writer. He recommended him to read Heart of Darkness and suggested he contact the author, Joseph Conrad, to see if he would support a public campaign for systemic reform. Casement and Conrad had met in the lower Congo in 1890 and a friendship had developed between the two men. The fact is, Naipaul provides powerful ammunition for all sides of the debate. Were Naipaul simply a monster, he (and his writing) would not be so compelling. Revealing himself to be a monster in one instance, he will use that very quality to his own advantage in the next. This protean quality makes Naipaul larger, as a character, a novelist, and a thinker, than any of the categories meant to encompass him. Those, for instance, who want to dismiss Naipaul for what Wood calls his “conservatism”, find themselves, more often than not, moved by his “radical eyesight.” And vice versa. Inevitably, to read Naipaul is to experience a rather exciting push/pull of attraction and repulsion. You can see this even in the short quote from Packer’s review of the French biography above. Naipaul describes extremely ugly behavior. Further, he seems to take narcissistic pleasure (the word ‘narcissism’ comes up often in discussions of Naipaul) in doing so. But he ends with a thought that is sensitive and vulnerable. “I was utterly helpless. I have enormous sympathy for people who do strange things out of passion.” By turning his sympathy around, he elicits it from us.

The fact is, Naipaul provides powerful ammunition for all sides of the debate. Were Naipaul simply a monster, he (and his writing) would not be so compelling. Revealing himself to be a monster in one instance, he will use that very quality to his own advantage in the next. This protean quality makes Naipaul larger, as a character, a novelist, and a thinker, than any of the categories meant to encompass him. Those, for instance, who want to dismiss Naipaul for what Wood calls his “conservatism”, find themselves, more often than not, moved by his “radical eyesight.” And vice versa. Inevitably, to read Naipaul is to experience a rather exciting push/pull of attraction and repulsion. You can see this even in the short quote from Packer’s review of the French biography above. Naipaul describes extremely ugly behavior. Further, he seems to take narcissistic pleasure (the word ‘narcissism’ comes up often in discussions of Naipaul) in doing so. But he ends with a thought that is sensitive and vulnerable. “I was utterly helpless. I have enormous sympathy for people who do strange things out of passion.” By turning his sympathy around, he elicits it from us. Not long ago, Turner Classic Movies aired several episodes of the 1950s television show Omnibus in which that most engaging and passionate of teachers, Leonard Bernstein, aided by singers and instrumentalists, lectured on various musical subjects. The aim of Omnibus was to enrich the cultural life of the American public, and as such, it represented an early attempt at producing programming that was entertaining as well as educational. If you had tuned in to those Sunday afternoon and evening shows, you might have encountered the likes of Frank Lloyd Wright or William Saroyan or Orson Welles. Bernstein hosted seven programs (forerunners to his legendary Young People’s Concerts with the New York Philharmonic), which covered topics such as “What Makes Opera Grand,” “Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony,” and “The American Musical Comedy”—their illuminating content belying these somewhat sober titles. I happened upon the Bernstein mini-marathon when it was halfway over, though I did manage to add a few episodes to my DVR queue. A few evenings ago, I happily settled in to watch “The Music of J. S. Bach”—the most inspiring hour I’ve spent in front of the television in ages.

Not long ago, Turner Classic Movies aired several episodes of the 1950s television show Omnibus in which that most engaging and passionate of teachers, Leonard Bernstein, aided by singers and instrumentalists, lectured on various musical subjects. The aim of Omnibus was to enrich the cultural life of the American public, and as such, it represented an early attempt at producing programming that was entertaining as well as educational. If you had tuned in to those Sunday afternoon and evening shows, you might have encountered the likes of Frank Lloyd Wright or William Saroyan or Orson Welles. Bernstein hosted seven programs (forerunners to his legendary Young People’s Concerts with the New York Philharmonic), which covered topics such as “What Makes Opera Grand,” “Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony,” and “The American Musical Comedy”—their illuminating content belying these somewhat sober titles. I happened upon the Bernstein mini-marathon when it was halfway over, though I did manage to add a few episodes to my DVR queue. A few evenings ago, I happily settled in to watch “The Music of J. S. Bach”—the most inspiring hour I’ve spent in front of the television in ages. The eternal challenge is to answer grief with something that resembles love. To choose not just to sit around decrying hardship and injustice but instead to uncurl your fists and approach sorrow with grace, power, and, most incredibly, gratitude—not for the hurt itself but for the whole miraculous mess of being alive, this strange endowment of breath and blood. Most days, I believe that

The eternal challenge is to answer grief with something that resembles love. To choose not just to sit around decrying hardship and injustice but instead to uncurl your fists and approach sorrow with grace, power, and, most incredibly, gratitude—not for the hurt itself but for the whole miraculous mess of being alive, this strange endowment of breath and blood. Most days, I believe that  A bit more than 8000 years ago, the world suddenly cooled, leading to much drier summers for much of the Northern Hemisphere. The impact on early farmers must have been extreme, yet archaeologists know little about how they endured. Now, the remains of animal fat on broken pottery from one of the world’s oldest and most unusual protocities—known as Çatalhöyük—is finally giving scientists a window into these ancient peoples’ close call with catastrophe. “I think the authors have done an excellent job,” says John Marston, an environmental archaeologist at Boston University who wasn’t involved in the current study. “It shows the people of Çatalhöyük were incredibly resilient.” Today, Çatalhöyük is just a series of dusty, sun-baked ruins in central Turkey. But thousands of years ago it was a bustling prehistoric metropolis. From about 7500 B.C.E to 5700 B.C.E., early farmers grew wheat, barley, and peas, and raised sheep, goats, and cattle. At its height, some 10,000 people lived there. Among its more noteworthy features, Çatalhöyük’s inhabitants were

A bit more than 8000 years ago, the world suddenly cooled, leading to much drier summers for much of the Northern Hemisphere. The impact on early farmers must have been extreme, yet archaeologists know little about how they endured. Now, the remains of animal fat on broken pottery from one of the world’s oldest and most unusual protocities—known as Çatalhöyük—is finally giving scientists a window into these ancient peoples’ close call with catastrophe. “I think the authors have done an excellent job,” says John Marston, an environmental archaeologist at Boston University who wasn’t involved in the current study. “It shows the people of Çatalhöyük were incredibly resilient.” Today, Çatalhöyük is just a series of dusty, sun-baked ruins in central Turkey. But thousands of years ago it was a bustling prehistoric metropolis. From about 7500 B.C.E to 5700 B.C.E., early farmers grew wheat, barley, and peas, and raised sheep, goats, and cattle. At its height, some 10,000 people lived there. Among its more noteworthy features, Çatalhöyük’s inhabitants were  Vijay Prashad in The Hindu:

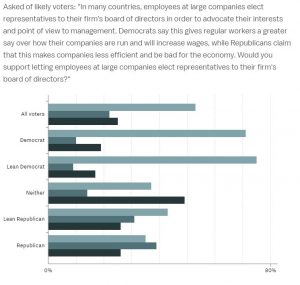

Vijay Prashad in The Hindu: Matthew Yglesias in Vox:

Matthew Yglesias in Vox: