Category: Archives

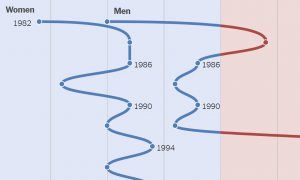

Exit Polls: How Voting Blocs Have Shifted From the ’80s to Now

K.K. Rebecca Lai and Allison McCann in the New York Times:

In the 2016 presidential election, 55 percent of white women voted for Republicans. And this year, the group backed Democrats and Republicans evenly.

In the 2016 presidential election, 55 percent of white women voted for Republicans. And this year, the group backed Democrats and Republicans evenly.

Historically, women, people of color and young voters have been more likely to cast ballots for Democrats, while men and wealthier voters have tended to favor Republicans. These demographic divisions held in 2018, but the last few decades of exit polls show that that has not always been the case.

The gender gap has remained relatively consistent since the 1980s, but it has been widening in recent years. Political scientists attribute this to women placing more of an emphasis on social welfare issues like health care and child care, which generally align with the Democratic Party, whereas men are more concerned with issues like taxes and national security.

More here.

John McDonnell shapes Labour case for four-day week

Dan Sabbagh in The Guardian:

John McDonnell, the Labour shadow chancellor, is in discussions with the distinguished economist Lord Skidelsky about an independent inquiry into cutting the working week, possibly from the traditional five days to four.

John McDonnell, the Labour shadow chancellor, is in discussions with the distinguished economist Lord Skidelsky about an independent inquiry into cutting the working week, possibly from the traditional five days to four.

The academic, who has a longstanding interest in the future of work, confirmed he was talking to the shadow chancellor about “the practical possibilities of reducing the working week”.

Skidelsky said he did not want to “be too exact” about his recommendations, although he added the idea of exploring ways of reducing the traditional five-day week to four was under consideration.

McDonnell has suggested the party could include a pledge to reduce the traditional working week by a day in its manifesto for the next election. Asked directly about this last month in a BBC interview, he said: “We will see how it goes.”

More here.

Saturday Poem

Art does not reproduce the visible, it makes visible.

–Paul Klee

With Two Camels and One Donkey

May we walk into our lives as into a watercolor,

grounded in sunlight, with two large ruminants and a baying ass.

May we go by foot, hot paving stones giving way to the Perfume Maker’s Souk,

cajoling two camels and the small-hoofed donkey.

May we improvise mosaics in the maize and indigo plazas,

with our crazy families, over acqueducts made famous by warring

Romans, and through decaying archways,

followed by two camels and one disagreeable donkey.

May we jam in the amphitheater and read aloud our odes to friends

who will love and disappoint and delight us in the melodies of friendship,

remembering to water two camels and one obstinate donkey.

In blowing sand that stings our faces, with recollection of our dead tenderly

wrapped and shaped like pyramids, may we sway

rhythmically on the backs of two camels and one moody donkey.

May we cherish the desert and embrace our memories of the sea,

knowing that one does not cancel out the other

but permits a cobalt-blue feather to grow in the mind.

May we gather in temporary shelters and break bread with others,

never allowing our envy to get out of hand and respecting the laws

of the lands we cross on two camels and one petulant donkey.

Thus, the painter invented this fanciful checkerboard grid,

this landscape of magic squares into which we may walk

with our lives and our deaths, with two camels and one recalcitrant donkey.

by Robin Becker

from Domain of Perfect Affection

University of Pittsburgh Press, 2006

Pretentious, impenetrable, hard work … better? Why we need difficult books

Sam Leith in The Guardian:

The fascination of what’s difficult,” wrote WB Yeats, “has dried the sap out of my veins … ” In the press coverage of this year’s Man Booker prize winner, Anna Burns’s Milkman, we’ve read a good many commentators presenting with sapless veins – but a dismaying lack of any sense that what’s difficult might be fascinating. “Odd”, “impenetrable”, “hard work”, “challenging” and “brain-kneading” have been some of the epithets chosen. They have not been meant, I think, as compliments. The chair of the judges, Kwame Anthony Appiah, perhaps unhelpfully, humblebragged that: “I spend my time reading articles in the Journal of Philosophy, so by my standards this is not too hard.” But he added that Milkman is “challenging […] the way a walk up Snowdon is challenging. It is definitely worth it because the view is terrific when you get to the top.”

The fascination of what’s difficult,” wrote WB Yeats, “has dried the sap out of my veins … ” In the press coverage of this year’s Man Booker prize winner, Anna Burns’s Milkman, we’ve read a good many commentators presenting with sapless veins – but a dismaying lack of any sense that what’s difficult might be fascinating. “Odd”, “impenetrable”, “hard work”, “challenging” and “brain-kneading” have been some of the epithets chosen. They have not been meant, I think, as compliments. The chair of the judges, Kwame Anthony Appiah, perhaps unhelpfully, humblebragged that: “I spend my time reading articles in the Journal of Philosophy, so by my standards this is not too hard.” But he added that Milkman is “challenging […] the way a walk up Snowdon is challenging. It is definitely worth it because the view is terrific when you get to the top.”

That’s at least a useful starting point. Appiah defends the idea – which, nearly a century after modernism really kicked off, probably shouldn’t need defending – that ease of consumption isn’t the main criterion by which literary value should be assessed. We like to see sportsmen and women doing difficult things. We tend to recognise in music, film, television and the plastic arts that good stuff often asks for a bit of work from its audience. And we’re all on board with “difficult” material as long as it’s a literary classic – we read The Waste Land for our A-levels and we scratched our heads as we puzzled it out, and now we recognise that it is like it is because it has to be that way. So why is “difficult” a problem when it comes to new fiction?

More here.

Tech C.E.O.s Are in Love With Their Principal Doomsayer

Nellie Bowles in The New York Times:

The futurist philosopher Yuval Noah Harari worries about a lot. He worries that Silicon Valley is undermining democracy and ushering in a dystopian hellscape in which voting is obsolete. He worries that by creating powerful influence machines to control billions of minds, the big tech companies are destroying the idea of a sovereign individual with free will. He worries that because the technological revolution’s work requires so few laborers, Silicon Valley is creating a tiny ruling class and a teeming, furious “useless class.” But lately, Mr. Harari is anxious about something much more personal. If this is his harrowing warning, then why do Silicon Valley C.E.O.s love him so? “One possibility is that my message is not threatening to them, and so they embrace it?” a puzzled Mr. Harari said one afternoon in October. “For me, that’s more worrying. Maybe I’m missing something?”

The futurist philosopher Yuval Noah Harari worries about a lot. He worries that Silicon Valley is undermining democracy and ushering in a dystopian hellscape in which voting is obsolete. He worries that by creating powerful influence machines to control billions of minds, the big tech companies are destroying the idea of a sovereign individual with free will. He worries that because the technological revolution’s work requires so few laborers, Silicon Valley is creating a tiny ruling class and a teeming, furious “useless class.” But lately, Mr. Harari is anxious about something much more personal. If this is his harrowing warning, then why do Silicon Valley C.E.O.s love him so? “One possibility is that my message is not threatening to them, and so they embrace it?” a puzzled Mr. Harari said one afternoon in October. “For me, that’s more worrying. Maybe I’m missing something?”

…Part of the reason might be that Silicon Valley, at a certain level, is not optimistic on the future of democracy. The more of a mess Washington becomes, the more interested the tech world is in creating something else, and it might not look like elected representation. Rank-and-file coders have long been wary of regulation and curious about alternative forms of government. A separatist streak runs through the place: Venture capitalists periodically call for California to secede orshatter, or for the creation of corporate nation-states. And this summer, Mark Zuckerberg, who has recommended Mr. Harari to his book club, acknowledged a fixation with the autocrat Caesar Augustus. “Basically,” Mr. Zuckerberg told The New Yorker, “through a really harsh approach, he established 200 years of world peace.” Mr. Harari, thinking about all this, puts it this way: “Utopia and dystopia depends on your values.”

More here.

Friday, November 9, 2018

Should We Care About Inequality?

Daniel Zamora in Jacobin:

Following the sensational success of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, with no less than 2.5 million copies of the book sold worldwide, inequality is now widely perceived, to quote Bernie Sanders, as “the great moral issue of our time.” Clearly the shift is part of a wider transformation of American and European politics in the wake the 2008 crash that has turned the “1%” into an object of increasing attention. Marx’s Capital is now a bestseller in the “free enterprise” section of the Kindle store, Jacobin is considered a respectable place to be published, and socialism no longer looks like a failed rock band trying to climb on stage when the “party” is already over. On the contrary, if we are to believe Gloria Steinem, a Bernie Sanders rally is now the “place to be,” even “for the girls.”

Following the sensational success of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, with no less than 2.5 million copies of the book sold worldwide, inequality is now widely perceived, to quote Bernie Sanders, as “the great moral issue of our time.” Clearly the shift is part of a wider transformation of American and European politics in the wake the 2008 crash that has turned the “1%” into an object of increasing attention. Marx’s Capital is now a bestseller in the “free enterprise” section of the Kindle store, Jacobin is considered a respectable place to be published, and socialism no longer looks like a failed rock band trying to climb on stage when the “party” is already over. On the contrary, if we are to believe Gloria Steinem, a Bernie Sanders rally is now the “place to be,” even “for the girls.”

On closer scrutiny, however, it’s not entirely clear how well our current interest in inequality (especially income inequality) rhymes with Marx’s own theory, or the ideas that dominated social-policy debates in decades following the Second World War. In fact, one could even argue that our current focus on income and wealth inequality, while crucial to any progressive agenda, also misses some of the most important aspects of the nineteenth-century critique of capitalism. At that time, “income inequality” was an elusive and at best ancillary term. In fact, the “monetization” of inequality is actually a relatively recent way of seeing the world — and, aside from its obvious strengths, it is also a way of seeing that, as the historian Pedro Ramos Pinto noted, has considerably “narrowed” the way we think about social justice.

More here.

Our favorite images from 2018’s Wildlife Photographer of the Year winners

More here.

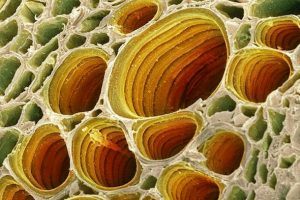

Billion-dollar bridges rarely fail—whereas billion-dollar drug failures are routine: How to Engineer Biology

Vijay Pande in Scientific American:

Because biology is the result of evolution and not human development, bringing engineering principles to it is guaranteed to fail. Or so goes the argument behind the “Grove fallacy,” first invoked by drug industry observer Derek Lowe in a critique of Intel CEO Andy Grove in 2007. After being diagnosed with prostate cancer, Grove found himself frustrated by what he described as the “lack of real output” in pharma especially as compared to the drive of Moore’s Law in his own industry.

Because biology is the result of evolution and not human development, bringing engineering principles to it is guaranteed to fail. Or so goes the argument behind the “Grove fallacy,” first invoked by drug industry observer Derek Lowe in a critique of Intel CEO Andy Grove in 2007. After being diagnosed with prostate cancer, Grove found himself frustrated by what he described as the “lack of real output” in pharma especially as compared to the drive of Moore’s Law in his own industry.

This was a naive and invalid criticism from Silicon Valley outsiders, Lowe argued, because “medical research is different [and harder] than semiconductor research”—and “that’s partly because we didn’t build them. Making the things [like semiconductors] from the ground up is a real advantage when it comes to understanding them, but we started studying life after it had a few billion years head start.” So the very idea of engineering biology by nature is doomed to fail, he further wrote, given that “billions of years of evolutionary tinkering have led to something so complex and so strange that it can make the highest human-designed technology look like something built with sticks.”

But we’ve seen incredible advances in the world of biology and tech the last few years, from AI diagnosing cancer more accurately than humans do, to editing genes with CRISPR. So is it still true that the idea of bringing an engineering mindset to bio is another case of starry-eyed technologist solutionism?

More here. [Thanks to Ashutosh Jogalekar.]

Be Nice

Matt Dinan in The Hedgehog Review:

Growing up, I never considered myself to be particularly nice, perhaps because I’m from a rural part of New Brunswick, one of Canada’s Maritime Provinces—the conspicuously “nicest” region in a self-consciously nice country. My parents are nice in a way that almost beggars belief—my mother’s tact is such that the strongest condemnation in her arsenal is “Well, I wouldn’t say I don’t like it, per se…” As for me, teenage eye-rolls gave way to undergraduate seriousness, which gave way to graduate-student irony. I thought of Atlantic Canadian nice as a convenient way to avoid telling the truth about the way things are—a disingenuous evasion of the nasty truth about the world. Even the word nice seems the moral equivalent of “uninteresting”—anodyne, tedious, otiose.

Growing up, I never considered myself to be particularly nice, perhaps because I’m from a rural part of New Brunswick, one of Canada’s Maritime Provinces—the conspicuously “nicest” region in a self-consciously nice country. My parents are nice in a way that almost beggars belief—my mother’s tact is such that the strongest condemnation in her arsenal is “Well, I wouldn’t say I don’t like it, per se…” As for me, teenage eye-rolls gave way to undergraduate seriousness, which gave way to graduate-student irony. I thought of Atlantic Canadian nice as a convenient way to avoid telling the truth about the way things are—a disingenuous evasion of the nasty truth about the world. Even the word nice seems the moral equivalent of “uninteresting”—anodyne, tedious, otiose.

That’s why I remember being a bit shocked when my colleagues at my first job in Massachusetts kept informing me that I was “too nice” to share my opinion about something or someone. Didn’t they know they were speaking to a percipient and courageous truth-teller? Maybe it was my harrowing stint as a commuter in Worcester—why won’t these people on the MassPike in fact use their “blinkahs”?—or maybe becoming a dad softened me up, but I have, initially with some dismay, found myself increasingly enjoying trying to be nice.

But my newfound appreciation for niceness may have come too late: Niceness has fallen on hard times.

More here.

Robert Pinsky’s Favorite Poem Project: From “Song of the Open Road” by Walt Whitman

Boygenius Is Driven by the Spirit of Solidarity

Carrie Battan at The New Yorker:

In 2016, the singer-songwriters Julien Baker, Lucy Dacus, and Phoebe Bridgers, who were all in their early twenties, were living parallel lives. They’d proved themselves to be careful and accomplished writers and performers, and had begun to attract attention from critics and labels alike. Each artist had crafted a distinct sound: Baker, a recovered opioid addict from Memphis, whose musical upbringing was in the Christian church, makes spare and swelling music that draws from the melodies and the ritualized melancholy of the emo world. Bridgers, a Los Angeles native who worshipped Elliott Smith and starred in an Apple commercial at the age of twenty-one, makes folksy, acoustic rock songs whose wispiness cleverly masks their morbid and searing lyrics. (One of her best songs, “Funeral,” details the experience of singing at the funeral of a boy who died of a heroin overdose.) Dacus has a deep, rich voice and makes more conventional rock songs, which she sings from a calm remove. But the three share indisputable similarities: they approach indie rock from a deliberate and plaintive perspective that skews more toward emo, folk, and blues than toward punk, and they write the kind of lyrics that warrant close reading. They are dutiful about guitar-rock songwriting without being explicitly reverential to a particular era.

In 2016, the singer-songwriters Julien Baker, Lucy Dacus, and Phoebe Bridgers, who were all in their early twenties, were living parallel lives. They’d proved themselves to be careful and accomplished writers and performers, and had begun to attract attention from critics and labels alike. Each artist had crafted a distinct sound: Baker, a recovered opioid addict from Memphis, whose musical upbringing was in the Christian church, makes spare and swelling music that draws from the melodies and the ritualized melancholy of the emo world. Bridgers, a Los Angeles native who worshipped Elliott Smith and starred in an Apple commercial at the age of twenty-one, makes folksy, acoustic rock songs whose wispiness cleverly masks their morbid and searing lyrics. (One of her best songs, “Funeral,” details the experience of singing at the funeral of a boy who died of a heroin overdose.) Dacus has a deep, rich voice and makes more conventional rock songs, which she sings from a calm remove. But the three share indisputable similarities: they approach indie rock from a deliberate and plaintive perspective that skews more toward emo, folk, and blues than toward punk, and they write the kind of lyrics that warrant close reading. They are dutiful about guitar-rock songwriting without being explicitly reverential to a particular era.

more here.

How The World We Live in Already Happened in 1992

John Ganz at The Baffler:

Who was the main enemy now? On the right, the answer increasingly was one another. In the 1980s, the conservative movement split into two warring factions—neoconservatives and paleo conservatives. The two sects fought over ideas, but also resources: comfortable think tank positions and administrative posts; grant money and the allegiance of the idle army of increasingly ideologically restive conservative activists who could scare up campaign contributions and votes.

Who was the main enemy now? On the right, the answer increasingly was one another. In the 1980s, the conservative movement split into two warring factions—neoconservatives and paleo conservatives. The two sects fought over ideas, but also resources: comfortable think tank positions and administrative posts; grant money and the allegiance of the idle army of increasingly ideologically restive conservative activists who could scare up campaign contributions and votes.

The tribes huddled around their magazines, from whose pages they launched their slings and arrows. The capital of neoconland was Norman Podhoretz’s Commentary; major outposts were Tyrrell’s The American Spectator and Irving Kristol’s National Interest. Podhoretz and Kristol’s sons went into the family business. In the paleo mind, the Podhoretzes and Kristols were like two great feudal dynasties that would shower fellowship money on loyal retainers. The prominence of these two Jewish families in the conservative movement fed darker fantasies, too.

more here.

Philosophy of the Bedroom

Lisa Hilton at the TLS:

“Before the bedroom there was the room, before that almost nothing”, Perrot announces. She chooses to leapfrog over much medieval history and begin with a description of the king’s bedroom at Versailles under Louis XIV – an account for which she relies heavily on the memoirs of the duc de Saint-Simon, who spoke to the Sun King twice. Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie is more thorough as an interpreter of the stultifying etiquette of the Versailles system, and Nancy Mitford much funnier; there is no fresh research or information in Perrot’s summary, which is at best indecisive as to the significance of the royal bedroom: “the king’s chamber guards its mysteries”. That said, we learn that Perrot intends to trace the origin of the desire for a “room of one’s own”, which mark of individualization is apparently less universal than it might appear. The Japanese had no notion of privacy, we are told, which might have come as news to the ukiyo-e artists of the seventeenth century; nonetheless, Perrot is broadly correct in her account of the evolution of private sleeping space as depending on the movement from curtained or boxed beds to separate chambers during the same period in Europe.

“Before the bedroom there was the room, before that almost nothing”, Perrot announces. She chooses to leapfrog over much medieval history and begin with a description of the king’s bedroom at Versailles under Louis XIV – an account for which she relies heavily on the memoirs of the duc de Saint-Simon, who spoke to the Sun King twice. Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie is more thorough as an interpreter of the stultifying etiquette of the Versailles system, and Nancy Mitford much funnier; there is no fresh research or information in Perrot’s summary, which is at best indecisive as to the significance of the royal bedroom: “the king’s chamber guards its mysteries”. That said, we learn that Perrot intends to trace the origin of the desire for a “room of one’s own”, which mark of individualization is apparently less universal than it might appear. The Japanese had no notion of privacy, we are told, which might have come as news to the ukiyo-e artists of the seventeenth century; nonetheless, Perrot is broadly correct in her account of the evolution of private sleeping space as depending on the movement from curtained or boxed beds to separate chambers during the same period in Europe.

more here.

Enlightenment without end

John Gray in New Statesman:

According to David Wootton, we are living in a world created by an intellectual revolution initiated by three thinkers in the 16th to 18th centuries. “My title is, Power, Pleasure and Profit, in that order, because power was conceptualised first, in the 16th century, by Niccolò Machiavelli; in the 17th century Hobbes radically revised the concepts of pleasure and happiness; and the way in which profit works in the economy was first adequately theorised in the 18th century by Adam Smith.” Before these thinkers, life had been based on the idea of a summum bonum – an all-encompassing goal of human life. Christianity identified it with salvation, Greco-Roman philosophy with a condition in which happiness and virtue were one and the same. For both, human life was complete when the supreme good was achieved.

According to David Wootton, we are living in a world created by an intellectual revolution initiated by three thinkers in the 16th to 18th centuries. “My title is, Power, Pleasure and Profit, in that order, because power was conceptualised first, in the 16th century, by Niccolò Machiavelli; in the 17th century Hobbes radically revised the concepts of pleasure and happiness; and the way in which profit works in the economy was first adequately theorised in the 18th century by Adam Smith.” Before these thinkers, life had been based on the idea of a summum bonum – an all-encompassing goal of human life. Christianity identified it with salvation, Greco-Roman philosophy with a condition in which happiness and virtue were one and the same. For both, human life was complete when the supreme good was achieved.

But for those who live in the world made by Machiavelli, Hobbes and Smith, there is no supreme good. Rather than salvation or virtue they want power, pleasure and profit – and they want them all without measure, limitlessly. Partly this is because these are scarce and highly unstable goods, craved by competitors and exposed to the accidents of fortune, hard to acquire and easily lost. A deeper reason is that for these thinkers human fulfilment is something that is pursued, not achieved. Human desire is insatiable and satisfaction an imaginary condition. Hobbes summarised this bleak view pithily: “So that in the first place I put for a general inclination of all mankind a perpetual and restless desire of power after power, that ceaseth only in death.” As Wootton notes, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards voiced a similar view of the human condition in their song “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”. Whether they knew it or not, the lyric captured the ruling world-view of modern times.

More here.

The Cat Who Could Predict Death

Siddhartha Mukherjee in Tonic:

Of the many small humiliations heaped on a young oncologist in his final year of fellowship, perhaps this one carried the oddest bite: A 2-year-old black-and-white cat named Oscar was apparently better than most doctors at predicting when a terminally ill patient was about to die. The story appeared, astonishingly, in The New England Journal of Medicine in the summer of 2007. Adopted as a kitten by the medical staff, Oscar reigned over one floor of the Steere House nursing home in Rhode Island. When the cat would sniff the air, crane his neck and curl up next to a man or woman, it was a sure sign of impending demise. The doctors would call the families to come in for their last visit. Over the course of several years, the cat had curled up next to 50 patients. Every one of them died shortly thereafter. No one knows how the cat acquired his formidable death-sniffing skills. Perhaps Oscar’s nose learned to detect some unique whiff of death — chemicals released by dying cells, say. Perhaps there were other inscrutable signs. I didn’t quite believe it at first, but Oscar’s acumen was corroborated by other physicians who witnessed the prophetic cat in action. As the author of the article wrote: “No one dies on the third floor unless Oscar pays a visit and stays awhile.”

Of the many small humiliations heaped on a young oncologist in his final year of fellowship, perhaps this one carried the oddest bite: A 2-year-old black-and-white cat named Oscar was apparently better than most doctors at predicting when a terminally ill patient was about to die. The story appeared, astonishingly, in The New England Journal of Medicine in the summer of 2007. Adopted as a kitten by the medical staff, Oscar reigned over one floor of the Steere House nursing home in Rhode Island. When the cat would sniff the air, crane his neck and curl up next to a man or woman, it was a sure sign of impending demise. The doctors would call the families to come in for their last visit. Over the course of several years, the cat had curled up next to 50 patients. Every one of them died shortly thereafter. No one knows how the cat acquired his formidable death-sniffing skills. Perhaps Oscar’s nose learned to detect some unique whiff of death — chemicals released by dying cells, say. Perhaps there were other inscrutable signs. I didn’t quite believe it at first, but Oscar’s acumen was corroborated by other physicians who witnessed the prophetic cat in action. As the author of the article wrote: “No one dies on the third floor unless Oscar pays a visit and stays awhile.”

The story carried a particular resonance for me that summer, for I had been treating S., a 32-year-old plumber with esophageal cancer. He had responded well to chemotherapy and radiation, and we had surgically resected his esophagus, leaving no detectable trace of malignancy in his body. One afternoon, a few weeks after his treatment had been completed, I cautiously broached the topic of end-of-life care. We were going for a cure, of course, I told S., but there was always the small possibility of a relapse. He had a young wife and two children, and a mother who had brought him weekly to the chemo suite. Perhaps, I suggested, he might have a frank conversation with his family about his goals?

More here.

Thursday, November 8, 2018

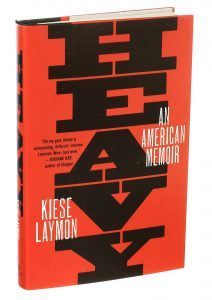

In ‘Heavy,’ Kiese Laymon Recalls the Weight of Where He’s Been

Jennifer Szalai in the New York Times:

Kiese Laymon started his new memoir, “Heavy,” with every intention of writing what his mother would have wanted — something profoundly uplifting and profoundly dishonest, something that did “that old black work of pandering” to American myths and white people’s expectations. His mother, a professor of political science, taught him that you need to lie as a matter of course and, ultimately, to survive; honesty could get a black boy growing up in Jackson, Miss., not just hurt but killed. He wanted to do what she wanted. But then he didn’t.

Kiese Laymon started his new memoir, “Heavy,” with every intention of writing what his mother would have wanted — something profoundly uplifting and profoundly dishonest, something that did “that old black work of pandering” to American myths and white people’s expectations. His mother, a professor of political science, taught him that you need to lie as a matter of course and, ultimately, to survive; honesty could get a black boy growing up in Jackson, Miss., not just hurt but killed. He wanted to do what she wanted. But then he didn’t.

“Heavy” is a gorgeous, gutting book that’s fueled by candor yet freighted with ambivalence. It’s full of devotion and betrayal, euphoria and anguish, tender embraces and rough abuse. Laymon addresses himself to his mother, a “you” who appears in these pages as a brilliant, overwhelmed woman starting her academic career while raising a son on her own. She gave her only child daily writing assignments — less, it seems, to encourage his sense of discovery and curiosity than to inculcate him with the “excellence, education and accountability” that were the “requirements” for keeping him safe.

More here.

Noam Chomsky Calls Trump and Republican Allies “Criminally Insane”

John Horgan in Scientific American:

I don’t really have heroes, but if I did, Noam Chomsky would be at the top of my list. Who else has achieved such lofty scientific and moral standing? Linus Pauling, perhaps, and Einstein. Chomsky’s arguments about the roots of language, which he first set forth in the late 1950s, triggered a revolution in our modern understanding of the mind. Since the 1960s, when he protested the Vietnam War, Chomsky has also been a ferocious political critic, denouncing abuses of power wherever he sees them. Chomsky, who turns 90 on December 7, remains busy. He spent last month in Brazil speaking out against far-right politician Jair Bolsonaro, and he recently discussed the migrant caravan on the show “Democracy Now.” Chomsky, whom I first interviewed in 1990 (see my profile here), has had an enormous influence on my scientific and political views. His statement that we may always “learn more about human life and human personality from novels than from scientific psychology” could serve as an epigraph for my new book Mind-Body Problems (available for free here). Below he responds to my emailed questions with characteristic clarity and force. — John Horgan

I don’t really have heroes, but if I did, Noam Chomsky would be at the top of my list. Who else has achieved such lofty scientific and moral standing? Linus Pauling, perhaps, and Einstein. Chomsky’s arguments about the roots of language, which he first set forth in the late 1950s, triggered a revolution in our modern understanding of the mind. Since the 1960s, when he protested the Vietnam War, Chomsky has also been a ferocious political critic, denouncing abuses of power wherever he sees them. Chomsky, who turns 90 on December 7, remains busy. He spent last month in Brazil speaking out against far-right politician Jair Bolsonaro, and he recently discussed the migrant caravan on the show “Democracy Now.” Chomsky, whom I first interviewed in 1990 (see my profile here), has had an enormous influence on my scientific and political views. His statement that we may always “learn more about human life and human personality from novels than from scientific psychology” could serve as an epigraph for my new book Mind-Body Problems (available for free here). Below he responds to my emailed questions with characteristic clarity and force. — John Horgan

Do you ever chill out?

Would rather skip personal matters.

Your ideas about language have evolved over the decades. In what ways, if any, have they remained the same?

Some of the earliest assumptions, then tentative and only partially formed, have proven quite robust, among them that the human language capacity is a species property in a double sense: virtually uniform among humans apart from serious pathology, and unique to humans in its essential properties.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: David Poeppel on Thought, Language, and How to Understand the Brain

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Language comes naturally to us, but is also deeply mysterious. On the one hand, it manifests as a collection of sounds or marks on paper. On the other hand, it also conveys meaning – words and sentences refer to states of affairs in the outside world, or to much more abstract concepts. How do words and meaning come together in the brain? David Poeppel is a leading neuroscientist who works in many areas, with a focus on the relationship between language and thought. We talk about cutting-edge ideas in the science and philosophy of language, and how researchers have just recently climbed out from under a nineteenth-century paradigm for understanding how all this works.

Language comes naturally to us, but is also deeply mysterious. On the one hand, it manifests as a collection of sounds or marks on paper. On the other hand, it also conveys meaning – words and sentences refer to states of affairs in the outside world, or to much more abstract concepts. How do words and meaning come together in the brain? David Poeppel is a leading neuroscientist who works in many areas, with a focus on the relationship between language and thought. We talk about cutting-edge ideas in the science and philosophy of language, and how researchers have just recently climbed out from under a nineteenth-century paradigm for understanding how all this works.

More here.

Past Masters of the Postmodern

Simon Blackburn in Inference Review:

If anxiety about truth is very much in the air, it has been in the air for a very long time. Well before the advent of tweets and trolls, George Orwell expressed the fear that “the very concept of objective truth [was] fading out of the world.”1 Orwell’s anxieties were political. Truth was under attack by politicians and their propagandists. Our anxieties are cultural, the widespread sense that a number of philosophical theories have escaped the academic world, and, in the wild, are doing great harm. Writing in the otherwise staid European Molecular Biology Organization Report, Marcel Kuntz affirmed that “postmodernist thought is being used to attack the scientific worldview and undermine scientific truths; a disturbing trend that has gone unnoticed by a majority of scientists.”2

If anxiety about truth is very much in the air, it has been in the air for a very long time. Well before the advent of tweets and trolls, George Orwell expressed the fear that “the very concept of objective truth [was] fading out of the world.”1 Orwell’s anxieties were political. Truth was under attack by politicians and their propagandists. Our anxieties are cultural, the widespread sense that a number of philosophical theories have escaped the academic world, and, in the wild, are doing great harm. Writing in the otherwise staid European Molecular Biology Organization Report, Marcel Kuntz affirmed that “postmodernist thought is being used to attack the scientific worldview and undermine scientific truths; a disturbing trend that has gone unnoticed by a majority of scientists.”2

This view of postmodernism as an intellectual villain is very common.

Whatever postmodernism is in the arts, I am concerned with its philosophy of language, its view of truth. Familiar figures have, by now, become infamous: Jean Baudrillard, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Martin Heidegger, Frederic Jameson, Douglas Kellner, Jean-François Lyotard, and Richard Rorty. Philosophical postmodernists emphasized the possibility of different perspectives on things, or different interpretations of them. They denied the existence of unmediated or innocent observation, and were dubious about the distinction between facts and values, the analytic and the synthetic, the mind and the world. Skeptical about truth, and sensitive to shifts in culture, society, and history, they thought of words as tools, and believed that vocabularies survive because they enable us to cope, to meet our goals.

They mistrusted authority.

More here.