Feisal Naqvi in Dawn:

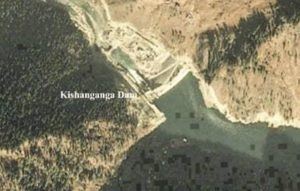

Imagine a case involving the most sensitive issues of national security possible. Imagine that Pakistan wins a conclusive victory in that case. Now imagine that Pakistan wastes that victory and spends 5 years blundering about in a dead end. Kishanganga is that case.

Imagine a case involving the most sensitive issues of national security possible. Imagine that Pakistan wins a conclusive victory in that case. Now imagine that Pakistan wastes that victory and spends 5 years blundering about in a dead end. Kishanganga is that case.

To restate the above paragraph in less dramatic terms, Pakistan’s dispute with India over the design of the Kishanganga Project involves vital aspects of national security. Whatever conclusion is reached will affect not just the Kishanganga Project but every subsequent project designed by India on the Western Rivers. Given the importance of water to our economy and our security, it is hard to imagine a more vital issue. Unfortunately, there is both good news and bad news to report.

The good news is that Pakistan did well in the first round of the Kishanganga dispute and received a favourable award from a seven-member Court of Arbitration. The bad news is that Pakistan has not taken advantage of this victory.

More here.

Debates over the extent to which racial attitudes and economic distress explain voting behavior in the 2016 election have tended to be limited in scope, focusing on the extent to which each factor explains white voters’ two-party vote choice. This limited scope obscures important ways in which these factors could have been related to voting behavior among other racial sub-groups of the electorate, as well as participation in the two-party contest in the first place. Using the vote-validated 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Survey, merged with economic data at the ZIP code and county levels, we find that racial attitudes strongly explain two-party vote choice among white voters—in line with a growing body of literature. However, we also find that local economic distress was strongly associated with non-voting among people of color, complicating direct comparisons between racial and economic explanations of the 2016 election and cautioning against generalizations regarding causal emphasis.

Debates over the extent to which racial attitudes and economic distress explain voting behavior in the 2016 election have tended to be limited in scope, focusing on the extent to which each factor explains white voters’ two-party vote choice. This limited scope obscures important ways in which these factors could have been related to voting behavior among other racial sub-groups of the electorate, as well as participation in the two-party contest in the first place. Using the vote-validated 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Survey, merged with economic data at the ZIP code and county levels, we find that racial attitudes strongly explain two-party vote choice among white voters—in line with a growing body of literature. However, we also find that local economic distress was strongly associated with non-voting among people of color, complicating direct comparisons between racial and economic explanations of the 2016 election and cautioning against generalizations regarding causal emphasis. Native Americans are only one percent of the population, but their images are on our boxes of butter and cornstarch. Their names are used to sell motorcycles and cars. And one of their brief encounters with English colonists is the basis of one of our biggest holidays. The story of Thanksgiving definitely evolved over time. The First Thanksgiving of 1621 happened but with little notice or attention. Curators at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian like to call it “a brunch in the forest.” Yes, it took place between Native Americans and Pilgrims. But the event was not exempt from history’s subjectivity. “What historians have had trouble explaining to civilians is that history is always a narrative. It always has a level of fiction in it,” says the Smithsonian’s Paul Chaat Smith. “That’s why the term ‘revisionist’ never really works,” he adds. “Because all history changes over time.” Smith is a co-curator of the National Museum of the American Indian’s highly acclaimed exhibition

Native Americans are only one percent of the population, but their images are on our boxes of butter and cornstarch. Their names are used to sell motorcycles and cars. And one of their brief encounters with English colonists is the basis of one of our biggest holidays. The story of Thanksgiving definitely evolved over time. The First Thanksgiving of 1621 happened but with little notice or attention. Curators at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian like to call it “a brunch in the forest.” Yes, it took place between Native Americans and Pilgrims. But the event was not exempt from history’s subjectivity. “What historians have had trouble explaining to civilians is that history is always a narrative. It always has a level of fiction in it,” says the Smithsonian’s Paul Chaat Smith. “That’s why the term ‘revisionist’ never really works,” he adds. “Because all history changes over time.” Smith is a co-curator of the National Museum of the American Indian’s highly acclaimed exhibition  For the microbiologist Justin Sonnenburg, that career-defining moment—the discovery that changed the trajectory of his research, inspiring him to study how diet and native microbes shape our risk for disease—came from a village in the African hinterlands. A group of Italian microbiologists had compared the intestinal microbes of young villagers in Burkina Faso with those of children in Florence, Italy. The villagers, who subsisted on a diet of mostly millet and sorghum, harbored far more microbial diversity than the Florentines, who ate a variant of the refined, Western diet. Where the Florentine microbial community was adapted to protein, fats, and simple sugars, the Burkina Faso microbiome was oriented toward degrading the complex plant carbohydrates we call fiber.

For the microbiologist Justin Sonnenburg, that career-defining moment—the discovery that changed the trajectory of his research, inspiring him to study how diet and native microbes shape our risk for disease—came from a village in the African hinterlands. A group of Italian microbiologists had compared the intestinal microbes of young villagers in Burkina Faso with those of children in Florence, Italy. The villagers, who subsisted on a diet of mostly millet and sorghum, harbored far more microbial diversity than the Florentines, who ate a variant of the refined, Western diet. Where the Florentine microbial community was adapted to protein, fats, and simple sugars, the Burkina Faso microbiome was oriented toward degrading the complex plant carbohydrates we call fiber. The discussion of Islam in world politics in recent years has tended to focus on how religion inspires or is used by a wide range of social movements, political parties, and militant groups. Less attention has been paid, however, to the question of how governments—particularly those in the Middle East—have incorporated Islam into their broader foreign policy conduct. Whether it is state support for transnational religious propagation, the promotion of religious interpretations that ensure regime survival, or competing visions of global religious leadership; these all embody what we term in this new report the “geopolitics of religious soft power.”

The discussion of Islam in world politics in recent years has tended to focus on how religion inspires or is used by a wide range of social movements, political parties, and militant groups. Less attention has been paid, however, to the question of how governments—particularly those in the Middle East—have incorporated Islam into their broader foreign policy conduct. Whether it is state support for transnational religious propagation, the promotion of religious interpretations that ensure regime survival, or competing visions of global religious leadership; these all embody what we term in this new report the “geopolitics of religious soft power.”

The share of Americans who say sex between unmarried adults is “not wrong at all” is at an all-time high. New cases of HIV are at an all-time low. Most women can—at last—get birth control for free, and the morning-after pill without a prescription.

The share of Americans who say sex between unmarried adults is “not wrong at all” is at an all-time high. New cases of HIV are at an all-time low. Most women can—at last—get birth control for free, and the morning-after pill without a prescription. At the chilling climax of William S. Lind’s 2014 novel “Victoria,” knights wearing crusader’s crosses and singing Christian hymns brutally slay the politically correct faculty at Dartmouth College, the main character’s (and Mr. Lind’s) alma mater. “The work of slaughter went quickly,” the narrator says. “In less than five minutes of screams, shrieks and howls, it was all over. The floor ran deep with the bowels of cultural Marxism.”

At the chilling climax of William S. Lind’s 2014 novel “Victoria,” knights wearing crusader’s crosses and singing Christian hymns brutally slay the politically correct faculty at Dartmouth College, the main character’s (and Mr. Lind’s) alma mater. “The work of slaughter went quickly,” the narrator says. “In less than five minutes of screams, shrieks and howls, it was all over. The floor ran deep with the bowels of cultural Marxism.” When I first read Marguerite Duras’s Moderato Cantabile for my high school AP French class, an alarm went off on me. That I was reading the words of someone who understood love in the same way I did. At that point in my life I hadn’t yet experienced love, but it didn’t matter. It was a foreshadowing of what was to come, of what I already knew to be true. The next year, in a college French class, I read Duras’s The Lover. From the first page (J’ai un visage détruit) I saw myself again. I felt recognized. But even as I was, in Kate Briggs’s words, underlining, typing the passage out, capturing it on my phone…even in its plenitude, even as it is right now filling me up, there is, I feel, something missing. What is missing is me: my action, my further activity…the audacious counteraction—of the active force that is me. Perhaps in reading these words, the ache that opened up in me was not from identification but from feeling that this writing wouldn’t be complete until I had acted my own force on it. The drive to translate—not for glory, not for recognition, not for money (obviously): to complete the text (in my eyes) by adding my own force to it. When I read a given book and feel the jolt Briggs describes as a matter of intensely felt identification, it’s not the text, it’s me in the text. In the words of Duras (in our translation of her), What moves me is myself.

When I first read Marguerite Duras’s Moderato Cantabile for my high school AP French class, an alarm went off on me. That I was reading the words of someone who understood love in the same way I did. At that point in my life I hadn’t yet experienced love, but it didn’t matter. It was a foreshadowing of what was to come, of what I already knew to be true. The next year, in a college French class, I read Duras’s The Lover. From the first page (J’ai un visage détruit) I saw myself again. I felt recognized. But even as I was, in Kate Briggs’s words, underlining, typing the passage out, capturing it on my phone…even in its plenitude, even as it is right now filling me up, there is, I feel, something missing. What is missing is me: my action, my further activity…the audacious counteraction—of the active force that is me. Perhaps in reading these words, the ache that opened up in me was not from identification but from feeling that this writing wouldn’t be complete until I had acted my own force on it. The drive to translate—not for glory, not for recognition, not for money (obviously): to complete the text (in my eyes) by adding my own force to it. When I read a given book and feel the jolt Briggs describes as a matter of intensely felt identification, it’s not the text, it’s me in the text. In the words of Duras (in our translation of her), What moves me is myself. This is also a musical biography that makes clear why, after all, we should bother to read a book about Chopin. Far from being a salon miniaturist, he was a major artist, a true heir to Bach and Mozart (as well as Beethoven, though he wouldn’t have liked it said), a creator of new forms, new modes of expression, and new keyboard techniques and sonorities. Walker rightly indicates Scriabin and Fauré as direct musical descendants, and Debussy as heir to Chopin’s discoveries about the piano; and since Debussy drew a new language partly from these findings, Walker might well have claimed (though he doesn’t) that Chopin lies behind a good deal of modern music, too. How’s that for a salon miniaturist?

This is also a musical biography that makes clear why, after all, we should bother to read a book about Chopin. Far from being a salon miniaturist, he was a major artist, a true heir to Bach and Mozart (as well as Beethoven, though he wouldn’t have liked it said), a creator of new forms, new modes of expression, and new keyboard techniques and sonorities. Walker rightly indicates Scriabin and Fauré as direct musical descendants, and Debussy as heir to Chopin’s discoveries about the piano; and since Debussy drew a new language partly from these findings, Walker might well have claimed (though he doesn’t) that Chopin lies behind a good deal of modern music, too. How’s that for a salon miniaturist? William H. Gass loved words. “A word is a wanderer,” he wrote in “Carrots, Noses, Snow, Rose, Roses.” “Except in the most general syntactical sense, it has no home.”

William H. Gass loved words. “A word is a wanderer,” he wrote in “Carrots, Noses, Snow, Rose, Roses.” “Except in the most general syntactical sense, it has no home.” “A geneticist, an oncologist, a roboticist, a novelist and an A.I. researcher walk into a bar.” That could be the setup for a very bad joke — or a tremendously fascinating conversation. Fortunately for us, it was the latter. On a blustery evening in late September, in a private room at a bar near Times Square, the magazine gathered five brilliant scientists and thinkers around a table for a three-hour dinner. In the (edited) transcript below — moderated by Mark Jannot, a story editor at the magazine and a former editor in chief of Popular Science — you can see what they had to say about the future of medicine, health care and humanity.

“A geneticist, an oncologist, a roboticist, a novelist and an A.I. researcher walk into a bar.” That could be the setup for a very bad joke — or a tremendously fascinating conversation. Fortunately for us, it was the latter. On a blustery evening in late September, in a private room at a bar near Times Square, the magazine gathered five brilliant scientists and thinkers around a table for a three-hour dinner. In the (edited) transcript below — moderated by Mark Jannot, a story editor at the magazine and a former editor in chief of Popular Science — you can see what they had to say about the future of medicine, health care and humanity. A couple of years ago, while working on my novel Home Fire, which required me to look into certain aspects of the UK’s citizenship laws, I had a slightly painful conversation with one of my oldest friends. Like me, she had grown up in Karachi. But while I didn’t move to the UK until the age of 34, she came here at 18 to go to university, and has never left. She became a British citizen soon after graduating (her grandmother was British); later, she married an Englishman, and they had a son. Her son was born in London, has never lived anywhere but here. But the painful thing I had to tell her was this: unlike many children who are born and live in the UK, her son’s claim on UK citizenship was contingent rather than assured. He was a British citizen, yes, but he could be made unBritish.

A couple of years ago, while working on my novel Home Fire, which required me to look into certain aspects of the UK’s citizenship laws, I had a slightly painful conversation with one of my oldest friends. Like me, she had grown up in Karachi. But while I didn’t move to the UK until the age of 34, she came here at 18 to go to university, and has never left. She became a British citizen soon after graduating (her grandmother was British); later, she married an Englishman, and they had a son. Her son was born in London, has never lived anywhere but here. But the painful thing I had to tell her was this: unlike many children who are born and live in the UK, her son’s claim on UK citizenship was contingent rather than assured. He was a British citizen, yes, but he could be made unBritish. It is an understatement to say that the 42-year-old [Tino] Sehgal is obsessive about his work, from its concept to the lexicon used to describe it. His practice has more to do with theater and acting techniques (many of his players are professional actors) than it does with the tradition of performance art, the de facto description for any kind of live experimentation in the art world. And it’s not strictly conceptual art, either, if one goes by

It is an understatement to say that the 42-year-old [Tino] Sehgal is obsessive about his work, from its concept to the lexicon used to describe it. His practice has more to do with theater and acting techniques (many of his players are professional actors) than it does with the tradition of performance art, the de facto description for any kind of live experimentation in the art world. And it’s not strictly conceptual art, either, if one goes by  The executive summary of the paper is this. They claim that the optical signal does not fit with the hypothesis that the event is a neutron-star merger. Instead, they argue, it looks like a specific type of white-dwarf merger. A white-dwarf merger, however, would not result in a gravitational wave signal strong enough to be measurable by LIGO. So, they conclude, there must be something wrong with the LIGO event. (The VIRGO measurement of that event has a signal-to-noise ratio of merely two, so it doesn’t increase the significance all that much.)

The executive summary of the paper is this. They claim that the optical signal does not fit with the hypothesis that the event is a neutron-star merger. Instead, they argue, it looks like a specific type of white-dwarf merger. A white-dwarf merger, however, would not result in a gravitational wave signal strong enough to be measurable by LIGO. So, they conclude, there must be something wrong with the LIGO event. (The VIRGO measurement of that event has a signal-to-noise ratio of merely two, so it doesn’t increase the significance all that much.) PANKAJ MISHRA: I know from experience that it is very easy for a brown-skinned Indian writer to be caricatured as a knee-jerk anti-American/anti-Westernist/Third-Worldist/angry postcolonial, and it is important then to point out that my understanding of modern imperialism and liberalism — like that of many people with my background — is actually grounded in an experience of Indian political realities.

PANKAJ MISHRA: I know from experience that it is very easy for a brown-skinned Indian writer to be caricatured as a knee-jerk anti-American/anti-Westernist/Third-Worldist/angry postcolonial, and it is important then to point out that my understanding of modern imperialism and liberalism — like that of many people with my background — is actually grounded in an experience of Indian political realities.