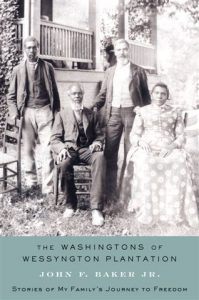

John Baker in BlackPast.Org:

When I was in the seventh grade, I spotted a photograph of four former slaves in my social studies textbook. Although the photograph was entitled Black Tennesseans, I noticed a strong family resemblance between them and my family members. When my grandmother told me that two of them were actually her grandparents, I began the lifelong research project that became The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation: Stories of My Family’s Journey to Freedom.

When I was in the seventh grade, I spotted a photograph of four former slaves in my social studies textbook. Although the photograph was entitled Black Tennesseans, I noticed a strong family resemblance between them and my family members. When my grandmother told me that two of them were actually her grandparents, I began the lifelong research project that became The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation: Stories of My Family’s Journey to Freedom.

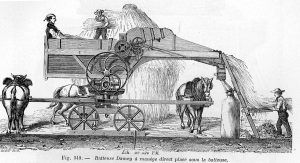

I tell the story of my ancestors Emanuel and Henny Washington, who were enslaved on Wessyngton Plantation owned by the Washington family. This is also the story of the hundreds of other African Americans connected with the plantation for more than two hundred years. It is a story of family, faith, and community. Founded in 1796 by Joseph Washington, a distant cousin of America’s first president, Wessyngton Plantation covered 15,000 acres in Robertson County and held an enslaved population of 274 African Americans. They comprised the largest enslaved population on a single plantation in the state of Tennessee and they worked on the largest tobacco plantation in the United States and the second largest in the world.

During the Civil War many African American men from the plantation enlisted in the Union Army, others ran away and worked on the military fortification, Fort Negley, in Nashville. After the emancipation in 1865 many of the freedpeople returned to Wessyngton as sharecroppers. Others purchased their own farms including several who bought land on which they had previously been enslaved. Some of this land remains in their descendants’ possession.

Only two slaves were ever sold from Wessyngton Plantation so the African Americans there formed family groups that remained intact for generations. Many of their descendants still remain in the area close to the plantation, others now numbering in the tens of thousands live throughout the United States. Some of the African Americans on Wessyngton also retained true African names, which was very rare for that period. This has made it possible to trace their African ethnic group heritage, which has been confirmed by DNA testing.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, we will publish at least one post dedicated to Black History Month)

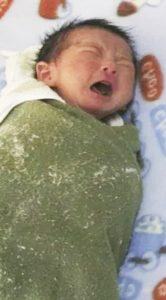

Most female flies take a low-rent approach to parenthood, depositing scores of seed-sized eggs in the trash or on pet scat to hatch, leaving the larvae to fend for themselves. Not so the female tsetse fly. She gestates her young internally, one at a time, and gives birth to them live. When each extravagantly pampered offspring pulls free of her uterus after nine days, fly mother and child are pretty much the same size. “It’s the equivalent of giving birth to an 18-year-old,” said Geoffrey Attardo, an entomologist who studies tsetse flies at the University of California, Davis. The newborn tsetse fly looks like a hand grenade and moves like a Slinky, and if you squeeze it too hard the source of its plumpness becomes clear — or rather a telltale white. The larva, it seems, is just a big bag of milk. “Rupture the gut,” Dr. Attardo said, “and the milk comes spilling out.”

Most female flies take a low-rent approach to parenthood, depositing scores of seed-sized eggs in the trash or on pet scat to hatch, leaving the larvae to fend for themselves. Not so the female tsetse fly. She gestates her young internally, one at a time, and gives birth to them live. When each extravagantly pampered offspring pulls free of her uterus after nine days, fly mother and child are pretty much the same size. “It’s the equivalent of giving birth to an 18-year-old,” said Geoffrey Attardo, an entomologist who studies tsetse flies at the University of California, Davis. The newborn tsetse fly looks like a hand grenade and moves like a Slinky, and if you squeeze it too hard the source of its plumpness becomes clear — or rather a telltale white. The larva, it seems, is just a big bag of milk. “Rupture the gut,” Dr. Attardo said, “and the milk comes spilling out.” A man is

A man is  In his 2008

In his 2008  The dystopia George Orwell conjured up in “1984” wasn’t a prediction. It was, instead, a reflection. Newspeak, the Ministry of Truth, the Inner Party, the Outer Party — that novel sampled and remixed a reality that Nazi and Soviet totalitarianism had already made apparent. Scary stuff, certainly, but maybe the more frightening dystopia is the one no one warned you about, the one you wake up one morning to realize you’re living inside.

The dystopia George Orwell conjured up in “1984” wasn’t a prediction. It was, instead, a reflection. Newspeak, the Ministry of Truth, the Inner Party, the Outer Party — that novel sampled and remixed a reality that Nazi and Soviet totalitarianism had already made apparent. Scary stuff, certainly, but maybe the more frightening dystopia is the one no one warned you about, the one you wake up one morning to realize you’re living inside.

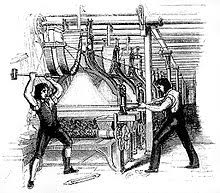

“Luddite” is a word that is thrown around a lot these days. It signifies someone who is opposed to technological progress, or who is at least not climbing on board the technological bandwagon. 21st century luddites tend to eschew social media, prefer presentations without PowerPoint, still write cheques, and may even, in extreme cases, get by without a cell phone. When used in the first person, “luddite” is often a badge of honour. “I’m a bit of a luddite,” usually means “I see through and am unimpressed by the false promise of constant technological novelty.” Used in the third person, though, it typically suggests criticism. “So-and-so’s a bit of a luddite,” is likely to imply that So-and-so finds the latest technology confusing and has failed to keep up with it, probably due to intellectual limitations.

“Luddite” is a word that is thrown around a lot these days. It signifies someone who is opposed to technological progress, or who is at least not climbing on board the technological bandwagon. 21st century luddites tend to eschew social media, prefer presentations without PowerPoint, still write cheques, and may even, in extreme cases, get by without a cell phone. When used in the first person, “luddite” is often a badge of honour. “I’m a bit of a luddite,” usually means “I see through and am unimpressed by the false promise of constant technological novelty.” Used in the third person, though, it typically suggests criticism. “So-and-so’s a bit of a luddite,” is likely to imply that So-and-so finds the latest technology confusing and has failed to keep up with it, probably due to intellectual limitations.

The traffic had been slow all day but by four pm, it was reduced to a trickle. Those cars that passed him on the street did so in two and threes as if they were sticking together for safety like lumbering animals caught out in a storm. It was, in fact, a very harsh winter day. The afternoon temperatures dipped well below zero: one of the coldest days ever recorded in Chicago. The only sounds now were from an occasional plane passing overhead, and from distant cackling from those venturesome neighbors who had left snug homes to experience the cold. He could hear the sound of his feet crunching through the snow.

The traffic had been slow all day but by four pm, it was reduced to a trickle. Those cars that passed him on the street did so in two and threes as if they were sticking together for safety like lumbering animals caught out in a storm. It was, in fact, a very harsh winter day. The afternoon temperatures dipped well below zero: one of the coldest days ever recorded in Chicago. The only sounds now were from an occasional plane passing overhead, and from distant cackling from those venturesome neighbors who had left snug homes to experience the cold. He could hear the sound of his feet crunching through the snow. One of the biggest early 20th century philosophical challenges to the belief in God stemmed from the doctrine of verificationism.

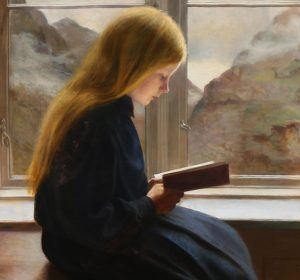

One of the biggest early 20th century philosophical challenges to the belief in God stemmed from the doctrine of verificationism. “I read books to read myself,” Sven Birkerts wrote in The Gutenberg Elegies: The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age. Birkerts’s book, which turns twenty-five this year, is composed of fifteen essays on reading, the self, the convergence of the two, and the ways both are threatened by the encroachment of modern technology. As the culture around him underwent the sea change of the internet’s arrival, Birkerts feared that qualities long safeguarded and elevated by print were in danger of erosion: among them privacy, the valuation of individual consciousness, and an awareness of history—not merely the facts of it, but a sense of its continuity, of our place among the centuries and cosmos. “Literature holds meaning not as a content that can be abstracted and summarized, but as experience,” he wrote. “It is a participatory arena. Through the process of reading we slip out of our customary time orientation, marked by distractedness and surficiality, into the realm of duration.”

“I read books to read myself,” Sven Birkerts wrote in The Gutenberg Elegies: The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age. Birkerts’s book, which turns twenty-five this year, is composed of fifteen essays on reading, the self, the convergence of the two, and the ways both are threatened by the encroachment of modern technology. As the culture around him underwent the sea change of the internet’s arrival, Birkerts feared that qualities long safeguarded and elevated by print were in danger of erosion: among them privacy, the valuation of individual consciousness, and an awareness of history—not merely the facts of it, but a sense of its continuity, of our place among the centuries and cosmos. “Literature holds meaning not as a content that can be abstracted and summarized, but as experience,” he wrote. “It is a participatory arena. Through the process of reading we slip out of our customary time orientation, marked by distractedness and surficiality, into the realm of duration.”

British scholar David Harvey is one of the most renowned Marxist scholars in the world today. His course on Karl Marx’s Capital is highly popular and has even been turned into a series on YouTube. Harvey is known for his support of student activism, community and labour movements.

British scholar David Harvey is one of the most renowned Marxist scholars in the world today. His course on Karl Marx’s Capital is highly popular and has even been turned into a series on YouTube. Harvey is known for his support of student activism, community and labour movements. With his finely tuned editing ear, Benjamin Dreyer often encounters things so personally horrifying that they register as a kind of torture, the way you might feel if you were an epicure and saw someone standing over the sink, slurping mayonnaise directly from the jar.

With his finely tuned editing ear, Benjamin Dreyer often encounters things so personally horrifying that they register as a kind of torture, the way you might feel if you were an epicure and saw someone standing over the sink, slurping mayonnaise directly from the jar. Davos 2019 was a downbeat affair. That at least is how regulars

Davos 2019 was a downbeat affair. That at least is how regulars