Jen Chaney in New York Magazine:

No, but seriously. We considered other very good series for this honor but kept coming back to Fleabag, the same way Fleabag, the character created and played by the magnificent Phoebe Waller-Bridge, keeps going back to the Priest during the perfect second season of this fantastic series. The attraction can’t be denied.

No, but seriously. We considered other very good series for this honor but kept coming back to Fleabag, the same way Fleabag, the character created and played by the magnificent Phoebe Waller-Bridge, keeps going back to the Priest during the perfect second season of this fantastic series. The attraction can’t be denied.

The six episodes that comprise season two landed on Amazon Prime on May 17, two months after its initial U.K. airing on BBC, and the same weekend that the Game of Thrones finale aired. After a couple days of GOT-ending outrage and disappointment, Fleabag took over the TV discourse. The most massive show on television, one with dragons and battles that take days to shoot and has millions upon millions of viewers, was quickly overshadowed by a series about a woman resisting her feelings for a priest.

When people finished bingeing that second season, it was as if they wanted to shout their love for it from rooftops. The day after one of my best friends made her way through it, she texted me, “I finished Fleabag. Nothing will ever be that good again.” It didn’t even sound like hyperbole.

More here. [Thanks to Maeve Adams.]

When cells are no longer needed, they die with what can only be called great dignity,” Bill Bryson wrote in A Short History of Nearly Everything. The received wisdom has long been that this march toward oblivion, once sufficiently advanced, cannot be reversed. But as science charts the contours of cellular function in ever-greater detail, a more fluid conception of cellular life and death has begun to gain the upper hand.

When cells are no longer needed, they die with what can only be called great dignity,” Bill Bryson wrote in A Short History of Nearly Everything. The received wisdom has long been that this march toward oblivion, once sufficiently advanced, cannot be reversed. But as science charts the contours of cellular function in ever-greater detail, a more fluid conception of cellular life and death has begun to gain the upper hand. “I can’t imagine him doing anything that’s not good for the country.” In an

“I can’t imagine him doing anything that’s not good for the country.” In an  Here’s a thought. Teen angst, once regarded as stubbornly generic, is actually a product of each person’s unique circumstances: gender, race, class, era. Angst is universal, but the content of it is particular. This might explain why Holden Caulfield, once the universal everyteen, does not speak to this generation in the way he’s spoken to young people in the past.

Here’s a thought. Teen angst, once regarded as stubbornly generic, is actually a product of each person’s unique circumstances: gender, race, class, era. Angst is universal, but the content of it is particular. This might explain why Holden Caulfield, once the universal everyteen, does not speak to this generation in the way he’s spoken to young people in the past.

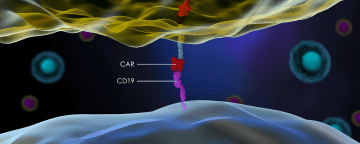

Despite the recent approval of two cancer therapies that use CAR T cells to treat lymphoma, 25 percent of eligible patients still choose to enter clinical trials instead of undergoing the available treatments. That’s according to insurance claims analyzed by health care consulting firm Vizient,

Despite the recent approval of two cancer therapies that use CAR T cells to treat lymphoma, 25 percent of eligible patients still choose to enter clinical trials instead of undergoing the available treatments. That’s according to insurance claims analyzed by health care consulting firm Vizient,

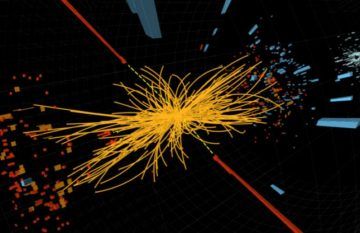

The trickiest part of hunting for new elementary particles is sifting through the massive amounts of data to find telltale patterns, or “signatures,” for those particles—or, ideally, weird patterns that don’t fit any known particle, an indication of new physics beyond the so-called

The trickiest part of hunting for new elementary particles is sifting through the massive amounts of data to find telltale patterns, or “signatures,” for those particles—or, ideally, weird patterns that don’t fit any known particle, an indication of new physics beyond the so-called  The British quit India in 1947. A blood-soaked partition had torn the subcontinent into two states that became the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the Republic of India, the latter comprising many faiths but secular. Or attempting to be: India was left with not so much a separation of state and religion as an intention to embrace all traditions evenly.

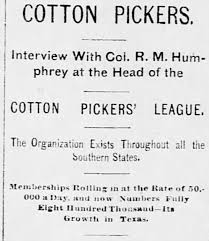

The British quit India in 1947. A blood-soaked partition had torn the subcontinent into two states that became the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the Republic of India, the latter comprising many faiths but secular. Or attempting to be: India was left with not so much a separation of state and religion as an intention to embrace all traditions evenly. It has not always been the case, after all, that American academics saw populism in terms of “identity.” In the 1920s, American historians could still look back fondly on the Populist episode as one of the many episodes in the age-long American class struggle. To followers of Charles A. Beard, doyen of the Progressive School in American History, Populism represented the last revolt of the small freeholding class, who, while being crushed by the advent of the industrial society, protested their new market-dependency by uniting on class lines. Other writers in this tradition, such as Vernon Parrington or John Hicks, shared their sentiments. Parrington’s Main Currents of American Thought (1927) cast “populism” as the revolt of small property-holders upholding the Jeffersonian ideal, sharing a pedigree which went back to the Founders’ Age. John Hicks’ classic The Populist Revolt (1931) tracked a similar genealogy, trying to show how the aims of the original Populist movement were translated into the working-class agitation of the incipient New Deal. Another classic of Populist historiography, Comer Vann Woodward’s Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel (1937), made a similar diagnosis of the economic character of the “agrarian crusade” which took Southern states by storm in the 1880s and 1890s.

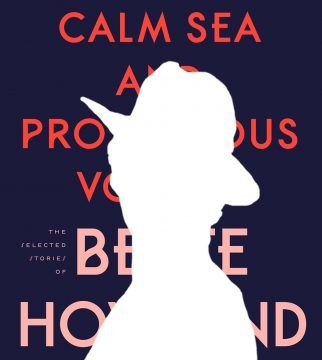

It has not always been the case, after all, that American academics saw populism in terms of “identity.” In the 1920s, American historians could still look back fondly on the Populist episode as one of the many episodes in the age-long American class struggle. To followers of Charles A. Beard, doyen of the Progressive School in American History, Populism represented the last revolt of the small freeholding class, who, while being crushed by the advent of the industrial society, protested their new market-dependency by uniting on class lines. Other writers in this tradition, such as Vernon Parrington or John Hicks, shared their sentiments. Parrington’s Main Currents of American Thought (1927) cast “populism” as the revolt of small property-holders upholding the Jeffersonian ideal, sharing a pedigree which went back to the Founders’ Age. John Hicks’ classic The Populist Revolt (1931) tracked a similar genealogy, trying to show how the aims of the original Populist movement were translated into the working-class agitation of the incipient New Deal. Another classic of Populist historiography, Comer Vann Woodward’s Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel (1937), made a similar diagnosis of the economic character of the “agrarian crusade” which took Southern states by storm in the 1880s and 1890s. The obituary reads: Author, Protégée of Bellow’s. Two defining characteristics of a life. Equally weighted, side by side. Bette Howland has been known, when she was known, by her proximity to male greatness. Just as Sylvia Plath is rarely mentioned without the appendage of Ted Hughes, Howland’s name, and her writing, reach us within the context of her position as protégée, friend to, and occasional lover of Saul Bellow.

The obituary reads: Author, Protégée of Bellow’s. Two defining characteristics of a life. Equally weighted, side by side. Bette Howland has been known, when she was known, by her proximity to male greatness. Just as Sylvia Plath is rarely mentioned without the appendage of Ted Hughes, Howland’s name, and her writing, reach us within the context of her position as protégée, friend to, and occasional lover of Saul Bellow. It took more than a hundred years, but physicists finally woke up, looked quantum mechanics into the face – and realized with bewilderment they barely know the theory they’ve been married to for so long. Gone are the days of “shut up and calculate”; the foundations of quantum mechanics are en vogue again.

It took more than a hundred years, but physicists finally woke up, looked quantum mechanics into the face – and realized with bewilderment they barely know the theory they’ve been married to for so long. Gone are the days of “shut up and calculate”; the foundations of quantum mechanics are en vogue again. “Democracy may not exist, but we’ll miss it when it’s gone” — or so suggests the title of Astra Taylor’s

“Democracy may not exist, but we’ll miss it when it’s gone” — or so suggests the title of Astra Taylor’s

This is the tale of a man who fled from desperate confinement, whirled into Polynesian dreamlands on a plank, sailed back to “civilization,” and then, his genius predictably unremunerated, had to tour the universe in a little room. His biographer calls him “an unfortunate fellow who had come to maturity penniless and poorly educated.” Unfortunate was likewise how he ended. Who could have predicted the greatness that lay before Herman Melville?

This is the tale of a man who fled from desperate confinement, whirled into Polynesian dreamlands on a plank, sailed back to “civilization,” and then, his genius predictably unremunerated, had to tour the universe in a little room. His biographer calls him “an unfortunate fellow who had come to maturity penniless and poorly educated.” Unfortunate was likewise how he ended. Who could have predicted the greatness that lay before Herman Melville? A Japanese stem-cell scientist is the first to receive government support to create animal embryos that contain human cells and transplant them into surrogate animals since a ban on the practice was overturned earlier this year. Hiromitsu Nakauchi, who leads teams at the University of Tokyo and Stanford University in California, plans to grow human cells in mouse and rat embryos and then transplant those embryos into surrogate animals. Nakauchi’s ultimate goal is to produce animals with organs made of human cells that can, eventually, be transplanted into people. Until March, Japan explicitly forbade the growth of animal embryos containing human cells beyond 14 days or the transplant of such embryos into a surrogate uterus. That month, Japan’s education and science ministry

A Japanese stem-cell scientist is the first to receive government support to create animal embryos that contain human cells and transplant them into surrogate animals since a ban on the practice was overturned earlier this year. Hiromitsu Nakauchi, who leads teams at the University of Tokyo and Stanford University in California, plans to grow human cells in mouse and rat embryos and then transplant those embryos into surrogate animals. Nakauchi’s ultimate goal is to produce animals with organs made of human cells that can, eventually, be transplanted into people. Until March, Japan explicitly forbade the growth of animal embryos containing human cells beyond 14 days or the transplant of such embryos into a surrogate uterus. That month, Japan’s education and science ministry