Witold Rybczynski at The Hedgehog Review:

Architectural historians can easily stray into advocacy. Consider Sigfried Giedion, the Swiss author of Space, Time and Architecture and a self-appointed propagandist of early Modernism, or Henry-Russell Hitchcock, who with Philip Johnson curated the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art that launched the International Style in the United States. The late Vincent Scully, a Hitchcock student and longtime Yale professor of architectural history, was an advocate too, one of his early forays into advocacy being a book provocatively titled The Shingle Style Today: Or the Historian’s Revenge.

Architectural historians can easily stray into advocacy. Consider Sigfried Giedion, the Swiss author of Space, Time and Architecture and a self-appointed propagandist of early Modernism, or Henry-Russell Hitchcock, who with Philip Johnson curated the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art that launched the International Style in the United States. The late Vincent Scully, a Hitchcock student and longtime Yale professor of architectural history, was an advocate too, one of his early forays into advocacy being a book provocatively titled The Shingle Style Today: Or the Historian’s Revenge.

Scully’s book was based on a lecture he had given at Columbia University, and any reader who ever attended a Scully talk will hear his bardic tones in the lively text. Published by George Braziller in 1974 and still in print, the slim paperback—barely more than a hundred pages—is well worth revisiting. Scully captured a particular moment, when American architects, chomping impatiently at the bit, were feeling constrained by the straitjacket of the International Style and the heavy influence of Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe.

more here.

SAM GILLIAM’S 1980 painting Robbin’ Peter seethes with pigment. The colors densely clot in some areas and in others are scraped flat to reveal the weave of the raw fabric canvas. Reds and blues clump and splat and drip, interrupted by short linear marks dragged through the paint to create rhythmic grooves. The work is a puzzle-like collage of previous Gilliam paintings, which have been cut up, reassembled, and glued in patchwork-quilt fashion, and in fact it takes its name from a vernacular quilt pattern known as “Robbing Peter to Pay Paul”—conventionally, a two-color needlework with curved diamond seams and overlapping, interlocked quartered circles. The pattern is found on quilts across the United States from the nineteenth century to the present day and is sometimes called simply, as Gilliam’s title acknowledges, “Robbing Peter.”1 Part of “Chasers,” a series of nine-sided works that Gilliam made between circa 1980 and 1982, pursuing in the process his always restless experiments with texture, shape, and surface, the quilt painting is muscular and assertive, pressing into space with its thick, built-up impasto excrescences.

SAM GILLIAM’S 1980 painting Robbin’ Peter seethes with pigment. The colors densely clot in some areas and in others are scraped flat to reveal the weave of the raw fabric canvas. Reds and blues clump and splat and drip, interrupted by short linear marks dragged through the paint to create rhythmic grooves. The work is a puzzle-like collage of previous Gilliam paintings, which have been cut up, reassembled, and glued in patchwork-quilt fashion, and in fact it takes its name from a vernacular quilt pattern known as “Robbing Peter to Pay Paul”—conventionally, a two-color needlework with curved diamond seams and overlapping, interlocked quartered circles. The pattern is found on quilts across the United States from the nineteenth century to the present day and is sometimes called simply, as Gilliam’s title acknowledges, “Robbing Peter.”1 Part of “Chasers,” a series of nine-sided works that Gilliam made between circa 1980 and 1982, pursuing in the process his always restless experiments with texture, shape, and surface, the quilt painting is muscular and assertive, pressing into space with its thick, built-up impasto excrescences. As a sophomore in college, I completely earned the C+ that I received in a survey course called “British Literature.” There could be no blaming of the professor on my end, no skirting responsibility for those missed assignments, no excuse for having confused Belphoebe for Gloriana in Edmund Spenser’s

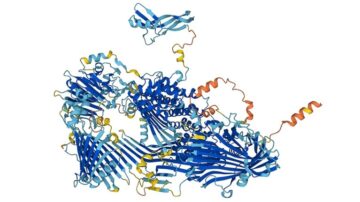

As a sophomore in college, I completely earned the C+ that I received in a survey course called “British Literature.” There could be no blaming of the professor on my end, no skirting responsibility for those missed assignments, no excuse for having confused Belphoebe for Gloriana in Edmund Spenser’s  Researchers have used the protein-structure-prediction tool AlphaFold to identify

Researchers have used the protein-structure-prediction tool AlphaFold to identify Your napkins need to be folded in a way that suggests you hold a degree in structural engineering.

Your napkins need to be folded in a way that suggests you hold a degree in structural engineering. You might think, with the completion of the Human Genome Project 20 years ago now, and the discovery of the double helix enjoying its 70th birthday this year, that we actually know how life works. In physics, the quest for a so-called Grand Unifying Theory has preoccupied the most ambitious minds for generations, alas to no avail. But in the life sciences, we managed to find four grand unifying theories in the space of 100 years or so. Three are well known: cell theory – all life is made of cells, which only come from existing cells; Darwin’s evolution by natural selection; and universal genetics – all life is encoded by a cypher written in the molecule DNA. The fourth, no less important, goes by the chewy name chemiosmosis, and describes the way that all living things live by drawing fuel from their surroundings and using it in a continuous chemical reaction. In summary, life, made of cells that extract energy from their environment, comes modified from what came before. Job done; suck it, physicists!

You might think, with the completion of the Human Genome Project 20 years ago now, and the discovery of the double helix enjoying its 70th birthday this year, that we actually know how life works. In physics, the quest for a so-called Grand Unifying Theory has preoccupied the most ambitious minds for generations, alas to no avail. But in the life sciences, we managed to find four grand unifying theories in the space of 100 years or so. Three are well known: cell theory – all life is made of cells, which only come from existing cells; Darwin’s evolution by natural selection; and universal genetics – all life is encoded by a cypher written in the molecule DNA. The fourth, no less important, goes by the chewy name chemiosmosis, and describes the way that all living things live by drawing fuel from their surroundings and using it in a continuous chemical reaction. In summary, life, made of cells that extract energy from their environment, comes modified from what came before. Job done; suck it, physicists! Since early December, the end of my 20-year career teaching at Harvard has been the subject of

Since early December, the end of my 20-year career teaching at Harvard has been the subject of  In his essay

In his essay  Depression is like waking up to a rainy, dreary morning, every single day. Activities that previously lightened the mood lose their joy. Instead, every social interaction and memory is filtered through a negative lens. This aspect of depression, called negative affective bias, leads to sadness and rumination—where haunting thoughts tumble around endlessly in the brain. Scientists have long sought to help people out of these ruts and back into a positive mindset by rewiring neural connections. Traditional antidepressants, such as Prozac,

Depression is like waking up to a rainy, dreary morning, every single day. Activities that previously lightened the mood lose their joy. Instead, every social interaction and memory is filtered through a negative lens. This aspect of depression, called negative affective bias, leads to sadness and rumination—where haunting thoughts tumble around endlessly in the brain. Scientists have long sought to help people out of these ruts and back into a positive mindset by rewiring neural connections. Traditional antidepressants, such as Prozac,  Tiny tardigrades have three claims to fame: their charmingly pudgy appearance, delightful common names (water bear and moss piglet) and stunning resilience in the face of threats ranging from the vacuum of space to temperatures near absolute zero. Now scientists have identified a key mechanism contributing to

Tiny tardigrades have three claims to fame: their charmingly pudgy appearance, delightful common names (water bear and moss piglet) and stunning resilience in the face of threats ranging from the vacuum of space to temperatures near absolute zero. Now scientists have identified a key mechanism contributing to  In 2000, Dickson D. Despommier, then a professor of public health and microbiology at Columbia University, was teaching a class on medical ecology in which he asked his students, “What will the world be like in 2050?,” and a follow-up, “What would you like the world to be like in 2050?” As Despommier

In 2000, Dickson D. Despommier, then a professor of public health and microbiology at Columbia University, was teaching a class on medical ecology in which he asked his students, “What will the world be like in 2050?,” and a follow-up, “What would you like the world to be like in 2050?” As Despommier  As I considered the invitation, I kept wondering why I’d been invited. I don’t write about CIA-adjacent topics, nor am I successful enough a novelist that people outside a small circle—one that I doubt includes U.S. intelligence agencies—know my name. So the invite was a bit of a mystery. This was the second-most common question that came up when I told writer friends about it, topped only by: “No speaking fee?” At first, I wondered whether the gig was part of a recruitment strategy. But it doesn’t take a vast intelligence apparatus to know that I am not intelligence material, not least because I am a professional writer.

As I considered the invitation, I kept wondering why I’d been invited. I don’t write about CIA-adjacent topics, nor am I successful enough a novelist that people outside a small circle—one that I doubt includes U.S. intelligence agencies—know my name. So the invite was a bit of a mystery. This was the second-most common question that came up when I told writer friends about it, topped only by: “No speaking fee?” At first, I wondered whether the gig was part of a recruitment strategy. But it doesn’t take a vast intelligence apparatus to know that I am not intelligence material, not least because I am a professional writer. The amount of electricity used to mine and trade

The amount of electricity used to mine and trade  As 2024 dawns, the prospects for a nuclear revival in the U.S. look mixed. On one hand, many once-skeptical environmentalists now support the technology. Bipartisan majorities in Congress back funding for nuclear research and deployment. And more than two dozen startups are developing a new generation of small, innovative reactor designs. But momentum slowed in November, when NuScale Power, the Portland, Oregon-based company pioneering small modular reactors (SMRs),

As 2024 dawns, the prospects for a nuclear revival in the U.S. look mixed. On one hand, many once-skeptical environmentalists now support the technology. Bipartisan majorities in Congress back funding for nuclear research and deployment. And more than two dozen startups are developing a new generation of small, innovative reactor designs. But momentum slowed in November, when NuScale Power, the Portland, Oregon-based company pioneering small modular reactors (SMRs),