Elisa Wouk Almino at the NYRB:

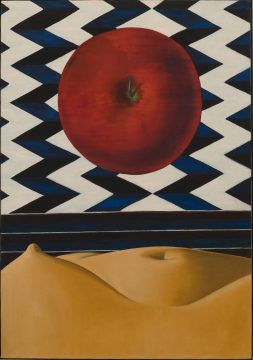

It wasn’t until Luchita Hurtado was ninety-nine years old that she would witness the opening of her first museum retrospective. Titled “I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn,” the exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) showcases the artist’s paintings, drawings, and sketches spanning eighty years. Inside the galleries in early February, she addressed the press, smiling, “This is one of the best moments of my life.”

It wasn’t until Luchita Hurtado was ninety-nine years old that she would witness the opening of her first museum retrospective. Titled “I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn,” the exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) showcases the artist’s paintings, drawings, and sketches spanning eighty years. Inside the galleries in early February, she addressed the press, smiling, “This is one of the best moments of my life.”

Hurtado spent much of her life mingling with and befriending some of the twentieth century’s best-known artists. She was close to Isamu Noguchi and once attended a party in Frida Kahlo’s hospital room. When she first met Marcel Duchamp, he gave Hurtado a foot massage. Jackson Pollock “scared the hell” out of her. But none of them knew Hurtado herself was an artist.

more here.

One might expect Ian Bremmer to be straightforwardly pessimistic in the current crisis. For one thing, the president of the Eurasia Group political risk consultancy is used to zipping around the world to meet business and political leaders. Now he is grounded and reckons any sort of new normal will take a very long time to emerge. “It’s weird,” he tells me down the phone from New York City. “I wasn’t prepared to put my life on hold for three years.” The US of all places is a gloomy spot at the moment, with more Covid-19 deaths than any other country and an increasingly ugly political mood ahead of November’s elections. Pessimism, of a sort, has been a good bet for Bremmer in the past. In 2011 he predicted a “G-Zero” world, an emerging power vacuum in international politics. The prediction has been borne out, he notes, both by trends evident at the time (a rising China reluctant to align with the West, a more self-contained US and a truculent Russia) and by others (technology driving populism, US energy independence, and the inequality bequeathed by the financial crisis) that have fully unfolded since.

One might expect Ian Bremmer to be straightforwardly pessimistic in the current crisis. For one thing, the president of the Eurasia Group political risk consultancy is used to zipping around the world to meet business and political leaders. Now he is grounded and reckons any sort of new normal will take a very long time to emerge. “It’s weird,” he tells me down the phone from New York City. “I wasn’t prepared to put my life on hold for three years.” The US of all places is a gloomy spot at the moment, with more Covid-19 deaths than any other country and an increasingly ugly political mood ahead of November’s elections. Pessimism, of a sort, has been a good bet for Bremmer in the past. In 2011 he predicted a “G-Zero” world, an emerging power vacuum in international politics. The prediction has been borne out, he notes, both by trends evident at the time (a rising China reluctant to align with the West, a more self-contained US and a truculent Russia) and by others (technology driving populism, US energy independence, and the inequality bequeathed by the financial crisis) that have fully unfolded since. The past couple of months have been heavy for us at The Scientist. Heavy for everyone. From our home offices, we’ve been tirelessly reporting on the global pandemic that continues to grip the world in its stranglehold. We are trying to stay atop a flood of information and stories that need telling as we also contend with challenges that most of us have never confronted, and none of us will likely soon forget. At the same time, we continue to search across the life sciences for other nuggets of research worth sharing. This month, our issue is focused on the science of memory. Our memories make us who we are, subconsciously driving our behaviors and dictating how we view the world. One of the most interesting things about memory is its imperfection. Rather than serving as a precise record of past events, our memories are more like concocted reflections, filtered and distilled from pure reality into a personal brew that is formulated by our own unique physiologies and emotional backgrounds. The wholly unique universe we each create—separate from but still tethered to the actual universe—is the product of electrical signals zapping through the lump of fatty flesh inside our skulls. Biology gives birth to something that exists outside the boundaries of biology.

The past couple of months have been heavy for us at The Scientist. Heavy for everyone. From our home offices, we’ve been tirelessly reporting on the global pandemic that continues to grip the world in its stranglehold. We are trying to stay atop a flood of information and stories that need telling as we also contend with challenges that most of us have never confronted, and none of us will likely soon forget. At the same time, we continue to search across the life sciences for other nuggets of research worth sharing. This month, our issue is focused on the science of memory. Our memories make us who we are, subconsciously driving our behaviors and dictating how we view the world. One of the most interesting things about memory is its imperfection. Rather than serving as a precise record of past events, our memories are more like concocted reflections, filtered and distilled from pure reality into a personal brew that is formulated by our own unique physiologies and emotional backgrounds. The wholly unique universe we each create—separate from but still tethered to the actual universe—is the product of electrical signals zapping through the lump of fatty flesh inside our skulls. Biology gives birth to something that exists outside the boundaries of biology. “Only when the tide goes out,” Warren Buffett observed, “do you discover who’s been swimming naked.” For our society, the Covid-19 pandemic represents an ebb tide of historic proportions, one that is laying bare vulnerabilities and inequities that in normal times have gone undiscovered. Nowhere is this more evident than in the American food system. A series of shocks has exposed weak links in our food chain that threaten to leave grocery shelves as patchy and unpredictable as those in the former Soviet bloc. The very system that made possible the bounty of the American supermarket—its vaunted efficiency and ability to “pile it high and sell it cheap”—suddenly seems questionable, if not misguided. But the problems the novel coronavirus has revealed are not limited to the way we produce and distribute food. They also show up on our plates, since the diet on offer at the end of the industrial food chain is linked to precisely the types of chronic disease that render us more vulnerable to Covid-19.

“Only when the tide goes out,” Warren Buffett observed, “do you discover who’s been swimming naked.” For our society, the Covid-19 pandemic represents an ebb tide of historic proportions, one that is laying bare vulnerabilities and inequities that in normal times have gone undiscovered. Nowhere is this more evident than in the American food system. A series of shocks has exposed weak links in our food chain that threaten to leave grocery shelves as patchy and unpredictable as those in the former Soviet bloc. The very system that made possible the bounty of the American supermarket—its vaunted efficiency and ability to “pile it high and sell it cheap”—suddenly seems questionable, if not misguided. But the problems the novel coronavirus has revealed are not limited to the way we produce and distribute food. They also show up on our plates, since the diet on offer at the end of the industrial food chain is linked to precisely the types of chronic disease that render us more vulnerable to Covid-19. Humans build machines, in part, to relieve themselves from the burden of work on difficult, repetitive tasks. And yet, despite the fact that machines are everywhere, most of us are still working pretty hard. But maybe that’s about to change. Futurists like John Danaher believe that society is finally on the brink of making a transition to a world in which work would be optional, rather than mandatory — and he thinks that’s a very good thing. It will take some adjusting, personally as well as economically, but he envisions a future in which human creativity and artistic impulse can flourish in a world free of the demands of working for a living. We talk about what that would entail, whether it’s realistic, and what comes next.

Humans build machines, in part, to relieve themselves from the burden of work on difficult, repetitive tasks. And yet, despite the fact that machines are everywhere, most of us are still working pretty hard. But maybe that’s about to change. Futurists like John Danaher believe that society is finally on the brink of making a transition to a world in which work would be optional, rather than mandatory — and he thinks that’s a very good thing. It will take some adjusting, personally as well as economically, but he envisions a future in which human creativity and artistic impulse can flourish in a world free of the demands of working for a living. We talk about what that would entail, whether it’s realistic, and what comes next.

On July 7, 2013, Keith Jarrett bracingly took to the stage at the Umbria Jazz Festival in Perugia, Italy. The momentousness of the occasion was not lost on anyone: just six years earlier, Jarrett had become the first artist to ever be banned from the festival by director Carlo Pagnotta, for delivering a profanity-ridden condemnation of photographers in the audience. Seeking to avoid a similar incident this time around, Pagnotta issued a preemptive plea to the crowd to put their cameras away and to greet Jarrett with a standing ovation.

On July 7, 2013, Keith Jarrett bracingly took to the stage at the Umbria Jazz Festival in Perugia, Italy. The momentousness of the occasion was not lost on anyone: just six years earlier, Jarrett had become the first artist to ever be banned from the festival by director Carlo Pagnotta, for delivering a profanity-ridden condemnation of photographers in the audience. Seeking to avoid a similar incident this time around, Pagnotta issued a preemptive plea to the crowd to put their cameras away and to greet Jarrett with a standing ovation. No emotion stands nearer to the foundational myths of the human social order than shame. In the beginning, Adam and Eve stood together ‘both naked, the man and his wife, and were not ashamed’. And then they ate of the tree of knowledge; their eyes opened; they knew they were naked; they covered themselves with fig leaves. Their shame was what told God they had fallen and become humans of our sort. Protagoras tells Socrates that after Prometheus had distinguished humans from other animals by giving them fire, Zeus gave them both shame and justice so that they could live together in harmony.

No emotion stands nearer to the foundational myths of the human social order than shame. In the beginning, Adam and Eve stood together ‘both naked, the man and his wife, and were not ashamed’. And then they ate of the tree of knowledge; their eyes opened; they knew they were naked; they covered themselves with fig leaves. Their shame was what told God they had fallen and become humans of our sort. Protagoras tells Socrates that after Prometheus had distinguished humans from other animals by giving them fire, Zeus gave them both shame and justice so that they could live together in harmony. IN A TELEGRAM SENT

IN A TELEGRAM SENT  Dreams have fascinated philosophers and artists for centuries. They have been seen as divine messages, a way of unleashing creativity and, since the advent of psychoanalysis in the 19th Century, the key to understanding our unconscious. As so many of us have been experiencing unusually vivid dreams in recent weeks, it seems an opportune moment to explore the way in which they have been understood and depicted throughout the centuries. In doing so we may even find some intriguing parallels with our own experiences. But why are we dreaming so vividly now? “We’re in a new situation so there’s new emotions to process,” says psychotherapist Philippa Perry, who was inundated with replies when she recently asked her followers to send her their dreams on Twitter. We make up narratives to make sense of those feelings that in dream manifest themselves “not straightforwardly but in metaphors”, she explains.

Dreams have fascinated philosophers and artists for centuries. They have been seen as divine messages, a way of unleashing creativity and, since the advent of psychoanalysis in the 19th Century, the key to understanding our unconscious. As so many of us have been experiencing unusually vivid dreams in recent weeks, it seems an opportune moment to explore the way in which they have been understood and depicted throughout the centuries. In doing so we may even find some intriguing parallels with our own experiences. But why are we dreaming so vividly now? “We’re in a new situation so there’s new emotions to process,” says psychotherapist Philippa Perry, who was inundated with replies when she recently asked her followers to send her their dreams on Twitter. We make up narratives to make sense of those feelings that in dream manifest themselves “not straightforwardly but in metaphors”, she explains. If we cannot resume economic activity without causing a resurgence of Covid-19 infections, we face a grim, unpredictable future of opening and closing schools and businesses.

If we cannot resume economic activity without causing a resurgence of Covid-19 infections, we face a grim, unpredictable future of opening and closing schools and businesses. ROBERT BRANDOM IS one of the few living philosophers who can, without exaggeration, be compared to the philosophical giants who once bestrode the earth, or at least loomed large in the study, from the 17th through the 19th centuries: Spinoza, Leibniz, Hume, Kant, Hegel — system-builders who intended to explain all of reality, and ourselves, to ourselves, insofar as we and it were explicable (a matter about which they disagreed). Brandom’s long-awaited book A Spirit of Trust is an achievement in that classical vein, and quite a surprising one in this period of punctilious specialists.

ROBERT BRANDOM IS one of the few living philosophers who can, without exaggeration, be compared to the philosophical giants who once bestrode the earth, or at least loomed large in the study, from the 17th through the 19th centuries: Spinoza, Leibniz, Hume, Kant, Hegel — system-builders who intended to explain all of reality, and ourselves, to ourselves, insofar as we and it were explicable (a matter about which they disagreed). Brandom’s long-awaited book A Spirit of Trust is an achievement in that classical vein, and quite a surprising one in this period of punctilious specialists.