Electric Elegy

Farewell, German radio with your green eye

and your bulky box,

together almost composing

a body and soul. (Your lamps glowed

with a pink, salmony light, like Bergson’s

deep self.)

……………. Through the thick fabric

of the speaker (my ear glued to you as

to the lattice of a confessional), Mussolini once whispered,

Hitler shouted, Stalin calmly explained,

Bierut hissed, Gomulka held endlessly forth.

But no one, radio, will accuse you of treason;

no, your only sin was obedience: absolute,

tender faithfulness to the megahertz;

whoever came was welcomed, whoever was sent

was received.

………………… Of course I know only

the songs of Schubert brought you the jade

of true joy. To Chopin’s waltzes

your electric heart throbbed delicately

and firmly and the cloth over the speaker

pulsated like the breasts of amorous girls

in old novels.

………………… Not with the news, though,

especially not Radio Free Europe or the BBC.

Then your eye would grow nervous,

the green pupil widen and shrink

as though its atropine dose had been altered.

Mad seagulls lived inside you, and Macbeth.

At night, forlorn signals found shelter

in your rooms, sailors cried for help,

the young comet cried, losing her head.

Your old age was announced by a cracked voice,

then rattles, coughing, and finally blindness

(your eye faded), and total silence.

Sleep peacefully, German radio,

dream Schumann and don’t waken

when the next dictator-rooster crows.

by Adam Zagajewsky

from The Vintage Book of Contemporary World Poetry

Vintage Books, 1996

Polish; trans. Renata Gorczynski,

Benjamin Ivry & C.K. Williams

Self’s overt commitment to the pursuit of self-derangement and the unchecked development of his independent sensibility mark him as one of the most unusual British writers of his time. His fiction, consisting mostly of satirical novels of the grotesque, is the product of deep-seated literary influences and intellectual orientations. The central reason that a broad perception of Self—who is known for writing books usually shunned as deliberately difficult, verbose, and unreadable—exists in Britain, is his public persona, mainly expressed on television panel shows. Through his great height (6’5”),

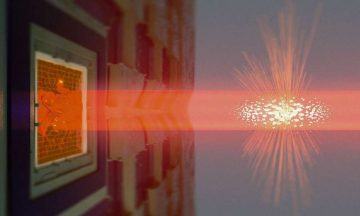

Self’s overt commitment to the pursuit of self-derangement and the unchecked development of his independent sensibility mark him as one of the most unusual British writers of his time. His fiction, consisting mostly of satirical novels of the grotesque, is the product of deep-seated literary influences and intellectual orientations. The central reason that a broad perception of Self—who is known for writing books usually shunned as deliberately difficult, verbose, and unreadable—exists in Britain, is his public persona, mainly expressed on television panel shows. Through his great height (6’5”),  A team of researchers at the Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, have succeeded in entangling two very different quantum objects. The result has several potential applications in ultra-precise sensing and quantum communication and is now published in Nature Physics.

A team of researchers at the Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, have succeeded in entangling two very different quantum objects. The result has several potential applications in ultra-precise sensing and quantum communication and is now published in Nature Physics.

The selected correspondence between Masham and Locke is fascinating to say the least. One of the exchanges treats the topic of religious enthusiasm. In response to Locke’s dismissal of religious enthusiasm as having no epistemological value, Masham notes that Locke might be thinking too narrowly of enthusiasm and indeed that there appears to be a version of it that readies the mind for reflection — a “Divine Sagacitie which is onely Competible to Persons of Pure and Unspoted Minds and without which Reason is not successful in the Contemplation of the Highest matters” (133-34). In another exchange, Masham presses Locke on how an empiricist can account for the formation of an idea of eternity in a finite human mind. Masham argues that the content of that idea does not represent eternity, but merely finite time repeated; that wouldn’t be an idea of eternity at all (184). Here she is gesturing at her own (Cambridge) Platonism and hinting that there are other entities about which Locke thinks we can reason — for example God — but where Lockean empiricism does not allow us to have ideas of them. Masham argues that at the very least finite minds are pre-formed with dispositions and traces, without which many of our ideas would never take shape (183). A third topic that is prominent in the exchanges between Masham and Locke is the question of whether or not the ethical doctrine of Stoicism can be lived by embodied human beings. For example, Masham says that if Epictetus and others are correct, then “Reason Teaches me . . . to be Contended with the World as it tis, and to make the Best of everything in it” (159).

The selected correspondence between Masham and Locke is fascinating to say the least. One of the exchanges treats the topic of religious enthusiasm. In response to Locke’s dismissal of religious enthusiasm as having no epistemological value, Masham notes that Locke might be thinking too narrowly of enthusiasm and indeed that there appears to be a version of it that readies the mind for reflection — a “Divine Sagacitie which is onely Competible to Persons of Pure and Unspoted Minds and without which Reason is not successful in the Contemplation of the Highest matters” (133-34). In another exchange, Masham presses Locke on how an empiricist can account for the formation of an idea of eternity in a finite human mind. Masham argues that the content of that idea does not represent eternity, but merely finite time repeated; that wouldn’t be an idea of eternity at all (184). Here she is gesturing at her own (Cambridge) Platonism and hinting that there are other entities about which Locke thinks we can reason — for example God — but where Lockean empiricism does not allow us to have ideas of them. Masham argues that at the very least finite minds are pre-formed with dispositions and traces, without which many of our ideas would never take shape (183). A third topic that is prominent in the exchanges between Masham and Locke is the question of whether or not the ethical doctrine of Stoicism can be lived by embodied human beings. For example, Masham says that if Epictetus and others are correct, then “Reason Teaches me . . . to be Contended with the World as it tis, and to make the Best of everything in it” (159). Nonetheless, Cézanne came to Pissarro to unlearn his first style, and, seemingly, to change his mind about Courbet, Manet and Delacroix; or at least about what might be made from them, from their attitudes (their subjects, their stances) and their materials. Provocation in art would give way to patience, to exposure to optical events. The word ‘humble’ which Cézanne chose years later to characterise Pissarro – ‘humble and colossal’, he called him, and perhaps even ‘justified in his anarchist theories’ – sums up a number of things. The way forward for French painting, Cézanne seems to have decided in 1873, was to be found in the style that Monet had built, and to which Pissarro had given his distinctive stamp, in the very years when Cézanne had built his massive contrary to Monet’s lightness and impersonality. (‘Monet, around 1869, he struck the great blow’ was Cézanne’s verdict in retrospect. ‘Monet and Pissarro, the two great masters, the only two.’) The Courbet, Manet and Delacroix in oneself, in other words – and no doubt the three remained heroes – would have to be painted out. Sometime in the winter of 1872-73 (I shall return to this later) Cézanne borrowed a landscape Pissarro had done two years before, in the first heyday of Impressionism, and sat down to copy it stroke by stroke.

Nonetheless, Cézanne came to Pissarro to unlearn his first style, and, seemingly, to change his mind about Courbet, Manet and Delacroix; or at least about what might be made from them, from their attitudes (their subjects, their stances) and their materials. Provocation in art would give way to patience, to exposure to optical events. The word ‘humble’ which Cézanne chose years later to characterise Pissarro – ‘humble and colossal’, he called him, and perhaps even ‘justified in his anarchist theories’ – sums up a number of things. The way forward for French painting, Cézanne seems to have decided in 1873, was to be found in the style that Monet had built, and to which Pissarro had given his distinctive stamp, in the very years when Cézanne had built his massive contrary to Monet’s lightness and impersonality. (‘Monet, around 1869, he struck the great blow’ was Cézanne’s verdict in retrospect. ‘Monet and Pissarro, the two great masters, the only two.’) The Courbet, Manet and Delacroix in oneself, in other words – and no doubt the three remained heroes – would have to be painted out. Sometime in the winter of 1872-73 (I shall return to this later) Cézanne borrowed a landscape Pissarro had done two years before, in the first heyday of Impressionism, and sat down to copy it stroke by stroke. A Supreme Court justice was dead, and the president, in his last year in office, quickly nominated a prominent lawyer to replace him. But the unlucky nominee’s bid was forestalled by the U.S. Senate, blocked due to the hostile politics of the time. It was 1852, but the doomed confirmation battle sounds a lot like 2016. “The nomination of Edward A. Bradford…as successor to Justice McKinley was postponed,” reported the New York Times on September 3, 1852. “This is equivalent to a rejection, contingent upon the result of the pending Presidential election. It is intended to reserve this vacancy to be supplied by Gen. Pierce, provided he be elected.”

A Supreme Court justice was dead, and the president, in his last year in office, quickly nominated a prominent lawyer to replace him. But the unlucky nominee’s bid was forestalled by the U.S. Senate, blocked due to the hostile politics of the time. It was 1852, but the doomed confirmation battle sounds a lot like 2016. “The nomination of Edward A. Bradford…as successor to Justice McKinley was postponed,” reported the New York Times on September 3, 1852. “This is equivalent to a rejection, contingent upon the result of the pending Presidential election. It is intended to reserve this vacancy to be supplied by Gen. Pierce, provided he be elected.” President

President  The translator is a writer. The writer is a translator. How many times have I run up against these assertions?—in a chat between translators protesting because they are not listed in a publisher’s index of authors; or in the work of literary theorists, even poets (“Each text is unique, yet at the same time it is the translation of another text,” observed Octavio Paz). Others claim that because language is referential, any written text is a translation of the world referred to.

The translator is a writer. The writer is a translator. How many times have I run up against these assertions?—in a chat between translators protesting because they are not listed in a publisher’s index of authors; or in the work of literary theorists, even poets (“Each text is unique, yet at the same time it is the translation of another text,” observed Octavio Paz). Others claim that because language is referential, any written text is a translation of the world referred to. There’s something strange about this coronavirus pandemic. Even after months of extensive research by the global scientific community, many questions remain open.

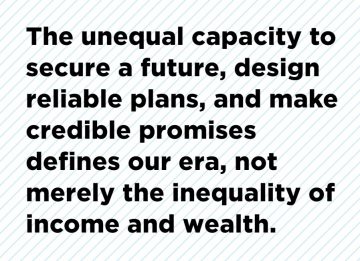

There’s something strange about this coronavirus pandemic. Even after months of extensive research by the global scientific community, many questions remain open. E. P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class relates the story of a Manchester silk weaver who, in 1835, complained of being subjugated to the urgent demands of the market. This skilled artisan observed how capitalists determined the pace at which they worked, while workers faced externally imposed timelines. “Labour,” the weaver lamented, “is always carried to market by those who have nothing else to keep or to sell, and who, therefore, must part with it immediately.” Rejecting any comparison of workers and capitalists, he stated, “if I, in an imitation of the capitalist” refused to sell what I have “because an inadequate price is offered me for it, can I bottle it? Can I lay it up in salt?” No, he bitterly answered, “labour cannot by any possibility be stored, but must be every instant sold or every instant lost.”

E. P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class relates the story of a Manchester silk weaver who, in 1835, complained of being subjugated to the urgent demands of the market. This skilled artisan observed how capitalists determined the pace at which they worked, while workers faced externally imposed timelines. “Labour,” the weaver lamented, “is always carried to market by those who have nothing else to keep or to sell, and who, therefore, must part with it immediately.” Rejecting any comparison of workers and capitalists, he stated, “if I, in an imitation of the capitalist” refused to sell what I have “because an inadequate price is offered me for it, can I bottle it? Can I lay it up in salt?” No, he bitterly answered, “labour cannot by any possibility be stored, but must be every instant sold or every instant lost.” “Chance in art” can mean many different things, so numerous and so varied that one may be tempted to dismiss the term as a misnomer or a lexical straw man, like so many adherents to the notion of divine or natural causality have done in the past: “Chance seems to be only a term, by which we express our ignorance of the cause of any thing.”1 But there may be a plane on which at least some of these meanings and forms meet and which can illuminate them—this essay will attempt to locate it.

“Chance in art” can mean many different things, so numerous and so varied that one may be tempted to dismiss the term as a misnomer or a lexical straw man, like so many adherents to the notion of divine or natural causality have done in the past: “Chance seems to be only a term, by which we express our ignorance of the cause of any thing.”1 But there may be a plane on which at least some of these meanings and forms meet and which can illuminate them—this essay will attempt to locate it. Wolfgang Koeppen’s novel Pigeons on the Grass, first published in 1951 as Tauben im Gras, is among the earliest, grandest, and most poetically satisfying reckonings in fiction with the postwar state of the world. What have we done to ourselves? What may we hope for? Is life from now on going to be different? Is it even going to be possible? These are the unasked and unanswerable questions that hover around this great novel composed in bite-size chunks, a cross section of a damaged society presented—natch!—in cutup. I once described it as a “Modernist jigsaw in 110 pieces,” but it is as compulsively readable as Dickens or Elmore Leonard. The form catches the eye, but the content is no slouch either. It must be one of the shortest of the universal books, the ones of which you think, If it isn’t in here, it doesn’t exist.

Wolfgang Koeppen’s novel Pigeons on the Grass, first published in 1951 as Tauben im Gras, is among the earliest, grandest, and most poetically satisfying reckonings in fiction with the postwar state of the world. What have we done to ourselves? What may we hope for? Is life from now on going to be different? Is it even going to be possible? These are the unasked and unanswerable questions that hover around this great novel composed in bite-size chunks, a cross section of a damaged society presented—natch!—in cutup. I once described it as a “Modernist jigsaw in 110 pieces,” but it is as compulsively readable as Dickens or Elmore Leonard. The form catches the eye, but the content is no slouch either. It must be one of the shortest of the universal books, the ones of which you think, If it isn’t in here, it doesn’t exist. The far-right Proud Boys group whom Donald Trump told to “stand by” during this week’s presidential debate is seen as a dangerous organization by law enforcement, according to leaked assessments of the organization from federal, state and local agencies. Trump’s refusal to condemn white supremacists during the debate, and his suggestion that the Proud Boys “stand by” during the current 2020 election campaign sent shockwaves through American politics. The Southern Poverty Law Center calls the Proud Boys a hate group. Files from the Blueleaks trove of leaked law enforcement documents reveal warnings that the Proud Boys, who some of the US agencies label as “white supremacists” and “extremists”, and others as a “gang”, show persistent concerns about the group’s menace to minority groups and even police officers, and its dissemination of dangerous conspiracy theories.

The far-right Proud Boys group whom Donald Trump told to “stand by” during this week’s presidential debate is seen as a dangerous organization by law enforcement, according to leaked assessments of the organization from federal, state and local agencies. Trump’s refusal to condemn white supremacists during the debate, and his suggestion that the Proud Boys “stand by” during the current 2020 election campaign sent shockwaves through American politics. The Southern Poverty Law Center calls the Proud Boys a hate group. Files from the Blueleaks trove of leaked law enforcement documents reveal warnings that the Proud Boys, who some of the US agencies label as “white supremacists” and “extremists”, and others as a “gang”, show persistent concerns about the group’s menace to minority groups and even police officers, and its dissemination of dangerous conspiracy theories.