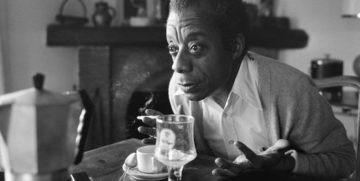

Bill V. Mullen in Literary Hub:

In 1985, Baldwin’s published and some unpublished essays were gathered in a single volume titled The Price of the Ticket. The book was significant for both looking backward, retrospectively and in a monumental manner, at the whole of Baldwin’s life, and forward, to the beginnings of the process of his memory and commemoration. By 1985, Baldwin’s literary production had become relatively meager. He was tired, winding down, traveling less, and camping out mainly at St. Paul-de-Vence. The lover he had lost to AIDS, according to David Leeming, died with him there, his ashes scattered around the property’s garden.

Baldwin was committed to two writing projects in these closing years of his life. The first, begun years earlier, was titled No Papers for Muhammad. According to Baldwin biographers James Campbell and David Leeming, the novel was to be based on Baldwin’s own frightening encounter with French immigration authorities—one perhaps fictionalized in David’s near apprehension by the police in “Les Evade’s”—and on the case of an Arab friend deported to Algeria.

Baldwin never completed the novel. However, important kernels and seedlings from it did manifest themselves in what became his final creative project, a play entitled The Welcome Table. Magdalena Zaborowska, in her superb book on Baldwin’s Turkish decade, refers to Baldwin’s The Welcome Table as a “last testament” to major life themes, including exile, erotics, and the multiple identities of the diasporic black subject. It is also, as Joseph Vogel noted, the only place in his creative writing where Baldwin made reference to the AIDS/HIV crisis.

More here.

Peter Hudis in Jacobin:

Peter Hudis in Jacobin: When Philippa Perry finished, after several years of writing and a lifetime of research, the first draft of her book about improving relationships between parents and children, she sent it to her editor – and their relationship promptly collapsed.

When Philippa Perry finished, after several years of writing and a lifetime of research, the first draft of her book about improving relationships between parents and children, she sent it to her editor – and their relationship promptly collapsed.  The question has confounded many: How does Pakistan stay alive?

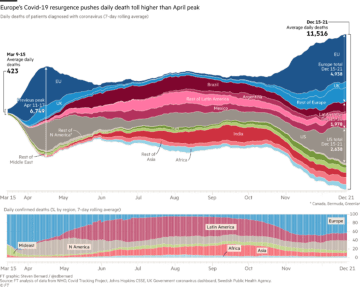

The question has confounded many: How does Pakistan stay alive? The human cost of coronavirus has continued to mount, with more than 77m cases confirmed globally and more than 1.69m people known to have died.

The human cost of coronavirus has continued to mount, with more than 77m cases confirmed globally and more than 1.69m people known to have died. Although the modern standard is officially exact, it isn’t actually exact. Two atomic clocks of the same design keep slightly different times. By statistically comparing atomic clocks, we know they are accurate to about one second in thirty million years. That’s probably accurate enough for everyday use, but it isn’t accurate enough for some scientific purposes. If we had more precise clocks, we could use them to study everything from geology to dark energy. So there is an ongoing quest to develop a new, more accurate standard.

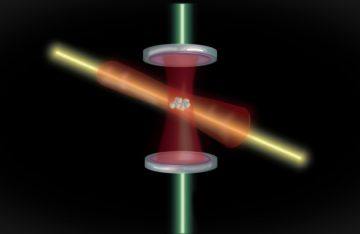

Although the modern standard is officially exact, it isn’t actually exact. Two atomic clocks of the same design keep slightly different times. By statistically comparing atomic clocks, we know they are accurate to about one second in thirty million years. That’s probably accurate enough for everyday use, but it isn’t accurate enough for some scientific purposes. If we had more precise clocks, we could use them to study everything from geology to dark energy. So there is an ongoing quest to develop a new, more accurate standard. Some plants are so entwined with tradition that it’s impossible to think of one without the other. Mistletoe is such a plant. But set aside the kissing custom and you’ll find a hundred and one reasons to appreciate the berry-bearing parasite for its very own sake. David Watson certainly does. So enamored is the mistletoe researcher that his home in Australia brims with mistletoe-themed items including wood carvings, ceramics and antique French tiles that decorate the bathroom and his pizza oven. And plant evolution expert Daniel Nickrent does, too: He has spent much of his life studying parasitic plants and, at his Illinois residence, has inoculated several maples in his yard — and his neighbor’s — with mistletoes. But the plants that entrance these and other mistletoe aficionados go far beyond the few species that are pressed into service around the holidays: usually the European Viscum album and a couple of Phoradendron species in North America, with their familiar oval green leaves and small white berries. Worldwide, there are more than a thousand mistletoe species. They grow on every continent except Antarctica — in deserts and tropical rain forests, on coastal heathlands and oceanic islands. And researchers are still learning about how they evolved and the tricks they use to set up shop in plants from ferns and grasses to pine and eucalyptus.

Some plants are so entwined with tradition that it’s impossible to think of one without the other. Mistletoe is such a plant. But set aside the kissing custom and you’ll find a hundred and one reasons to appreciate the berry-bearing parasite for its very own sake. David Watson certainly does. So enamored is the mistletoe researcher that his home in Australia brims with mistletoe-themed items including wood carvings, ceramics and antique French tiles that decorate the bathroom and his pizza oven. And plant evolution expert Daniel Nickrent does, too: He has spent much of his life studying parasitic plants and, at his Illinois residence, has inoculated several maples in his yard — and his neighbor’s — with mistletoes. But the plants that entrance these and other mistletoe aficionados go far beyond the few species that are pressed into service around the holidays: usually the European Viscum album and a couple of Phoradendron species in North America, with their familiar oval green leaves and small white berries. Worldwide, there are more than a thousand mistletoe species. They grow on every continent except Antarctica — in deserts and tropical rain forests, on coastal heathlands and oceanic islands. And researchers are still learning about how they evolved and the tricks they use to set up shop in plants from ferns and grasses to pine and eucalyptus. As a young child, I did not put much thought into who had led the Chinese against Japan. Once, at home, I had heard my father make a casual comment that the War of Resistance, as World War II is known in China, was mostly fought by the Nationalists. When I repeated the statement over dinner, my mother stared at her husband as if he were one of her disobedient students. After a long, awkward silence, she turned to look at me and said, “the Nationalists and the Communists cooperated,” before telling everyone at the table to never speak of this again.

As a young child, I did not put much thought into who had led the Chinese against Japan. Once, at home, I had heard my father make a casual comment that the War of Resistance, as World War II is known in China, was mostly fought by the Nationalists. When I repeated the statement over dinner, my mother stared at her husband as if he were one of her disobedient students. After a long, awkward silence, she turned to look at me and said, “the Nationalists and the Communists cooperated,” before telling everyone at the table to never speak of this again. It’s more than good news.

It’s more than good news.  Zara Houshmand: As an Iranian American, I’ve lived under the shadow of conflict between my two homes for much of my life, and it seemed to me that there was a strange irony there, a potentially fertile blind spot, and a possible bridge in Rumi’s popularity in America today. If he were alive today, Rumi probably wouldn’t get a visa to enter this country, though he’s clearly under our skin regardless.

Zara Houshmand: As an Iranian American, I’ve lived under the shadow of conflict between my two homes for much of my life, and it seemed to me that there was a strange irony there, a potentially fertile blind spot, and a possible bridge in Rumi’s popularity in America today. If he were alive today, Rumi probably wouldn’t get a visa to enter this country, though he’s clearly under our skin regardless. Schiff commented: “Reading him, we discover that we are all, like his secret agents, dissemblers selling our ‘covers’ to the world. We all have something to hide,” and we all want to align ourselves with a cause or a passion.

Schiff commented: “Reading him, we discover that we are all, like his secret agents, dissemblers selling our ‘covers’ to the world. We all have something to hide,” and we all want to align ourselves with a cause or a passion. HEIC ARTEMISIA the tombstone of Artemisia Gentileschi is said to have read. Clear and simple, forgoing the usual embellishments, such as names of father, husband, and children, dates of birth and death. HEIC ARTEMISIA, or HERE LIES ARTEMISIA.

HEIC ARTEMISIA the tombstone of Artemisia Gentileschi is said to have read. Clear and simple, forgoing the usual embellishments, such as names of father, husband, and children, dates of birth and death. HEIC ARTEMISIA, or HERE LIES ARTEMISIA. History used to be so much easier. There were the Wars of the Roses, then the Reformation, the Civil War, the Enlightenment and finally the Victorians. Each one had its own century and its distinctive tag. Throw in Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, garnish with a few zealots and adventurers, some glorious triumphs and some grisly deaths. It was all part of our Island Story. You knew where you were.

History used to be so much easier. There were the Wars of the Roses, then the Reformation, the Civil War, the Enlightenment and finally the Victorians. Each one had its own century and its distinctive tag. Throw in Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, garnish with a few zealots and adventurers, some glorious triumphs and some grisly deaths. It was all part of our Island Story. You knew where you were. In February of 1824, Charles Dickens watched in anguish as his father was arrested for debt and sent to the Marshalsea prison, just south of the Thames, in London. “I really believed at the time,” Dickens told his friend and biographer, John Forster, “that they had broken my heart.” Soon, Dickens’s mother and his younger siblings joined the father at Marshalsea, while a resentful Dickens earned money at a blacking factory, labelling pots of polish for shoes and boots. Although his father would be released within months, Dickens would never fully outrun the memory of his family’s incarceration. In her 2011 biography, Claire Tomalin notes that, in adulthood, Dickens became “an obsessive visitor of prisons.” In the autobiographical essay, “Night Walks,” he describes halting in the shadows of Newgate Prison, “touching its rough stone” and lingering “by that wicked little Debtors’ Door – shutting tighter than any other door one ever saw.” While touring America as a famous author, he made sure to go and see the prisons in Boston, New York, and Baltimore, among others.

In February of 1824, Charles Dickens watched in anguish as his father was arrested for debt and sent to the Marshalsea prison, just south of the Thames, in London. “I really believed at the time,” Dickens told his friend and biographer, John Forster, “that they had broken my heart.” Soon, Dickens’s mother and his younger siblings joined the father at Marshalsea, while a resentful Dickens earned money at a blacking factory, labelling pots of polish for shoes and boots. Although his father would be released within months, Dickens would never fully outrun the memory of his family’s incarceration. In her 2011 biography, Claire Tomalin notes that, in adulthood, Dickens became “an obsessive visitor of prisons.” In the autobiographical essay, “Night Walks,” he describes halting in the shadows of Newgate Prison, “touching its rough stone” and lingering “by that wicked little Debtors’ Door – shutting tighter than any other door one ever saw.” While touring America as a famous author, he made sure to go and see the prisons in Boston, New York, and Baltimore, among others. It was always predictable that the genome of Sars-CoV-2 would mutate. After all, that’s what viruses and other micro-organisms do. The Sars-CoV-2 genome accumulates around one or two mutations every month as it circulates. In fact, its rate of change is much lower than those of other viruses that we know about. For example, seasonal influenza mutates at such a rate that a new vaccine has to be introduced each year.

It was always predictable that the genome of Sars-CoV-2 would mutate. After all, that’s what viruses and other micro-organisms do. The Sars-CoV-2 genome accumulates around one or two mutations every month as it circulates. In fact, its rate of change is much lower than those of other viruses that we know about. For example, seasonal influenza mutates at such a rate that a new vaccine has to be introduced each year.