H.M. Naqvi in Literary Hub:

I was in Australia on the tail-end of my eastern book tour, the Last Book Tour perhaps, one that had taken me to Indonesia and Bangladesh earlier, when the plague, after circling for months, dove in for the kill. I left perhaps a week before Australia locked down and have wondered what would have happened if I got stuck Down Under, a world unfamiliar in ways I did not expect. During the tour, however, I spent time on the periphery of stages and outside hotel lobbies, smoking, chatting with local literary rock stars, the likes of Tara June Winch and Christos Tskiolkas. On the plane back home to Karachi, I began Christos’s The Slap, and what a fun ride it was. Christos takes the reader into the minds of very human, rounded, middle-class characters whose lives are upended by an occurrence at a family barbecue in suburban Melbourne. The Slap also helps make an unfamiliar world more familiar.

I was in Australia on the tail-end of my eastern book tour, the Last Book Tour perhaps, one that had taken me to Indonesia and Bangladesh earlier, when the plague, after circling for months, dove in for the kill. I left perhaps a week before Australia locked down and have wondered what would have happened if I got stuck Down Under, a world unfamiliar in ways I did not expect. During the tour, however, I spent time on the periphery of stages and outside hotel lobbies, smoking, chatting with local literary rock stars, the likes of Tara June Winch and Christos Tskiolkas. On the plane back home to Karachi, I began Christos’s The Slap, and what a fun ride it was. Christos takes the reader into the minds of very human, rounded, middle-class characters whose lives are upended by an occurrence at a family barbecue in suburban Melbourne. The Slap also helps make an unfamiliar world more familiar.

Although Covid, for reasons that remain epidemiologically opaque, did not strike Pakistan with the same violence with which it ravaged the region—China, Iran, and now India—I burrowed underground, deep underground upon my return. I don’t want to die before I’m done with my next novel.

More here.

Almost 60 years ago, in February 1961, two teams of scientists stumbled on a discovery at the same time. Sydney Brenner in Cambridge and Jim Watson at Harvard independently spotted that genes send short-lived RNA copies of themselves to little machines called ribosomes where they are translated into proteins. ‘Sydney got most of the credit, but I don’t mind,’ Watson sighed last week when I asked him about it. They had solved a puzzle that had held up genetics for almost a decade. The short-lived copies came to be called messenger RNAs — mRNAs – and suddenly they now promise a spectacular revolution in medicine.

Almost 60 years ago, in February 1961, two teams of scientists stumbled on a discovery at the same time. Sydney Brenner in Cambridge and Jim Watson at Harvard independently spotted that genes send short-lived RNA copies of themselves to little machines called ribosomes where they are translated into proteins. ‘Sydney got most of the credit, but I don’t mind,’ Watson sighed last week when I asked him about it. They had solved a puzzle that had held up genetics for almost a decade. The short-lived copies came to be called messenger RNAs — mRNAs – and suddenly they now promise a spectacular revolution in medicine. I’ve recently spent a good chunk of time engrossed in reading A Promised Land, the first volume of President Barack Obama’s memoirs. After four years of the most impulsive and unstable president of my lifetime, hearing Obama’s calm and judicious voice in my head was like having a long, comforting talk with an old friend. His retelling of the challenges of his first two and a half years, from the global financial crisis and the passage of Obamacare to the Democrats’ midterm collapse in 2010 and the successful operation to kill Osama bin Laden in May 2011, is full of revealing details and discerning insight.

I’ve recently spent a good chunk of time engrossed in reading A Promised Land, the first volume of President Barack Obama’s memoirs. After four years of the most impulsive and unstable president of my lifetime, hearing Obama’s calm and judicious voice in my head was like having a long, comforting talk with an old friend. His retelling of the challenges of his first two and a half years, from the global financial crisis and the passage of Obamacare to the Democrats’ midterm collapse in 2010 and the successful operation to kill Osama bin Laden in May 2011, is full of revealing details and discerning insight. A poem from Paula Meehan’s second collection, Pillow Talk (1994), is called “Autobiography”. Well, in some ways a Selected Poems is like an autobiography; it expresses a sense that the life lived to date, and the work done, have some weight and perhaps some unity. Also, all autobiographies are provisional, and a Selected does not have the terminal stamp of a Collected Poems. There may yet be – one hopes there will be – many surprises in store. But there are differences: the poems included in Paula Meehan’s Selected Poems do not tell the writer’s chronological story. Rather, many of them are revisitings of phases or moments in the poet’s life, from the varying perspectives of later days. They explore those enlightening moments, when new meanings emerge from well-remembered encounters, that may only come when there is a degree of distance, for example when the adult can see what the adults in her own earlier life were about, and divine the depths of their emotions.

A poem from Paula Meehan’s second collection, Pillow Talk (1994), is called “Autobiography”. Well, in some ways a Selected Poems is like an autobiography; it expresses a sense that the life lived to date, and the work done, have some weight and perhaps some unity. Also, all autobiographies are provisional, and a Selected does not have the terminal stamp of a Collected Poems. There may yet be – one hopes there will be – many surprises in store. But there are differences: the poems included in Paula Meehan’s Selected Poems do not tell the writer’s chronological story. Rather, many of them are revisitings of phases or moments in the poet’s life, from the varying perspectives of later days. They explore those enlightening moments, when new meanings emerge from well-remembered encounters, that may only come when there is a degree of distance, for example when the adult can see what the adults in her own earlier life were about, and divine the depths of their emotions. At other times and in other places, traditional ways of life, social classification, and metaphysical order gave shape and coherence to the course of life, providing a picture of aging well. Each period of life had its activities, duties, and forms of flourishing.

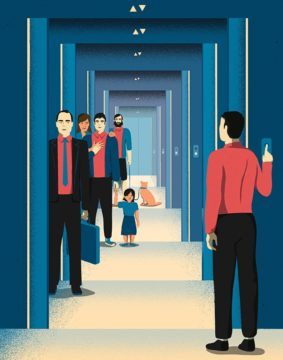

At other times and in other places, traditional ways of life, social classification, and metaphysical order gave shape and coherence to the course of life, providing a picture of aging well. Each period of life had its activities, duties, and forms of flourishing. Once, in another life, I was a tech founder. It was the late nineties, when the Web was young, and everyone was trying to cash in on the dot-com boom. In college, two of my dorm mates and I discovered that we’d each started an Internet company in high school, and we merged them to form a single, teen-age megacorp. For around six hundred dollars a month, we rented office space in the basement of a building in town. We made Web sites and software for an early dating service, an insurance-claims-processing firm, and an online store where customers could “bargain” with a cartoon avatar for overstock goods. I lived large, spending the money I made on tuition, food, and a stereo.

Once, in another life, I was a tech founder. It was the late nineties, when the Web was young, and everyone was trying to cash in on the dot-com boom. In college, two of my dorm mates and I discovered that we’d each started an Internet company in high school, and we merged them to form a single, teen-age megacorp. For around six hundred dollars a month, we rented office space in the basement of a building in town. We made Web sites and software for an early dating service, an insurance-claims-processing firm, and an online store where customers could “bargain” with a cartoon avatar for overstock goods. I lived large, spending the money I made on tuition, food, and a stereo. Gene drive organisms (GDOs), developed with select traits that are genetically engineered to spread through a population, have the power to dramatically alter the way society develops solutions to a range of daunting health and environmental challenges, from controlling dengue fever and malaria to protecting crops against plant pests.

Gene drive organisms (GDOs), developed with select traits that are genetically engineered to spread through a population, have the power to dramatically alter the way society develops solutions to a range of daunting health and environmental challenges, from controlling dengue fever and malaria to protecting crops against plant pests. This year marks the seventy-fifth anniversary of publication of

This year marks the seventy-fifth anniversary of publication of  For, whether we like it or not, it is a true fact that we are cousins of kangaroos, that we share an ancestor with starfish, and that we and the starfish and kangaroo share a more remote ancestor with jellyfish. The DNA code is a digital code, differing from computer codes only in being quaternary instead of binary. We know the precise details of the intermediate stages by which the code is read in our cells, and its four-letter alphabet translated, by molecular assembly-line machines called ribosomes, into a 20-letter alphabet of amino acids, the building blocks of protein chains and so of bodies.

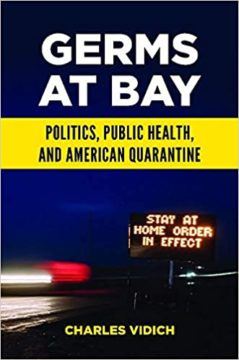

For, whether we like it or not, it is a true fact that we are cousins of kangaroos, that we share an ancestor with starfish, and that we and the starfish and kangaroo share a more remote ancestor with jellyfish. The DNA code is a digital code, differing from computer codes only in being quaternary instead of binary. We know the precise details of the intermediate stages by which the code is read in our cells, and its four-letter alphabet translated, by molecular assembly-line machines called ribosomes, into a 20-letter alphabet of amino acids, the building blocks of protein chains and so of bodies. As the US confronts both a political crisis of presidential succession and a worsening pandemic, it might be instructive, though perhaps not comforting, to learn that we’ve been here before.

As the US confronts both a political crisis of presidential succession and a worsening pandemic, it might be instructive, though perhaps not comforting, to learn that we’ve been here before. We are necessarily occupied here each week with strategies for getting ourselves out of the climate crisis—it is the world’s true Klaxon-sounding emergency. But it is worth occasionally remembering that global warming is just one measure of the human domination of our planet. We got another reminder of that unwise hegemony this week, from a study so remarkable that we should just pause and absorb it.

We are necessarily occupied here each week with strategies for getting ourselves out of the climate crisis—it is the world’s true Klaxon-sounding emergency. But it is worth occasionally remembering that global warming is just one measure of the human domination of our planet. We got another reminder of that unwise hegemony this week, from a study so remarkable that we should just pause and absorb it. This idea of Faulkner as fixated on the past has a long pedigree, perhaps beginning with “On The Sound and the Fury: Time in the Work of Faulkner,” a much-read 1939 essay by Jean-Paul Sartre. “In Faulkner’s work,” Sartre contends, “there is never any progression, never anything which comes from the future.” But what he describes in his quotations from the novel are Quentin Compson’s ruminations about time, not Faulkner’s. Sartre says that “Faulkner’s vision of the world can be compared to that of a man sitting in an open car and looking backwards.” But Sartre does not consider that in order for that vision to travel backwards the car has to move forward, and in that progress is change, which Warren Beck characterized as “man in motion” in his classic 1961 study, so titled, of the Snopes trilogy. Sartre—not the first philosopher to pursue an idea that overwhelms and distorts reality—argues that the past “takes on a sort of super-reality, its contours are hard and clear, unchangeable.” Tell that to any close reader of the 1936 novel Absalom, Absalom!, in which the past changes virtually moment by moment depending on who is talking.

This idea of Faulkner as fixated on the past has a long pedigree, perhaps beginning with “On The Sound and the Fury: Time in the Work of Faulkner,” a much-read 1939 essay by Jean-Paul Sartre. “In Faulkner’s work,” Sartre contends, “there is never any progression, never anything which comes from the future.” But what he describes in his quotations from the novel are Quentin Compson’s ruminations about time, not Faulkner’s. Sartre says that “Faulkner’s vision of the world can be compared to that of a man sitting in an open car and looking backwards.” But Sartre does not consider that in order for that vision to travel backwards the car has to move forward, and in that progress is change, which Warren Beck characterized as “man in motion” in his classic 1961 study, so titled, of the Snopes trilogy. Sartre—not the first philosopher to pursue an idea that overwhelms and distorts reality—argues that the past “takes on a sort of super-reality, its contours are hard and clear, unchangeable.” Tell that to any close reader of the 1936 novel Absalom, Absalom!, in which the past changes virtually moment by moment depending on who is talking. In 1938, Yasunari Kawabata, a young journalist in Tokyo, covered the battle between master Honinbo Shusai and apprentice Minoru Kitani for ultimate authority in the board game Go. It was one of the lengthiest matches in the history of competitive gaming—six months. In his 1968 Nobel Prize-winning novel inspired by these events, The Master of Go, Kawabata wrote of the decisive moment when, “Black has greater thickness and Black territory was secure, and the time was at hand for Otake’s [Kitani’s pseudonym in the book] own characteristic turn to offensive, for gnawing into enemy formations at which he was so adept.” A strategy that led Otake to victory.

In 1938, Yasunari Kawabata, a young journalist in Tokyo, covered the battle between master Honinbo Shusai and apprentice Minoru Kitani for ultimate authority in the board game Go. It was one of the lengthiest matches in the history of competitive gaming—six months. In his 1968 Nobel Prize-winning novel inspired by these events, The Master of Go, Kawabata wrote of the decisive moment when, “Black has greater thickness and Black territory was secure, and the time was at hand for Otake’s [Kitani’s pseudonym in the book] own characteristic turn to offensive, for gnawing into enemy formations at which he was so adept.” A strategy that led Otake to victory. The term “soft matter” was coined in 1970, and has become common currency in science only in the past two or three decades. Yet the substances to which it refers – such as honey, glue, flesh, soap, leather, starch, bitumen, milk, pastes and gels – have been familiar components of our material world since antiquity. The phrase, incidentally, was coined by French scientist Madeleine Veyssié, a collaborator of physics Nobel laureate Pierre-Gilles de Gennes, one of the foremost pioneers of the field. The French term, matière molle, is something of a double entendre, which would doubtless have appealed to the suave and charismatic de Gennes, well known for his almost stereotypically Gallic romantic liaisons.

The term “soft matter” was coined in 1970, and has become common currency in science only in the past two or three decades. Yet the substances to which it refers – such as honey, glue, flesh, soap, leather, starch, bitumen, milk, pastes and gels – have been familiar components of our material world since antiquity. The phrase, incidentally, was coined by French scientist Madeleine Veyssié, a collaborator of physics Nobel laureate Pierre-Gilles de Gennes, one of the foremost pioneers of the field. The French term, matière molle, is something of a double entendre, which would doubtless have appealed to the suave and charismatic de Gennes, well known for his almost stereotypically Gallic romantic liaisons.