Jonathan Kirshner in Boston Review:

Renoir himself claimed that a film director should have the arrogance to believe that he can change the world but the modesty to believe that if he succeeds in deeply moving four people, it’s a victory,” the great French director Bertrand Tavernier once observed. That wisdom may apply to Tavernier’s own 1992 documentary, La Guerre sans Nom (The War with No Name). Made in collaboration with historian Patrick Rotman, this four-hour film about the Algerian war—the most notable of the handful of documentaries Tavernier shot—did not make much of a splash in France, and it barely managed a few arthouse screenings in the United States before essentially disappearing from circulation. Its viewership stands to expand considerably, however, with its timely release to streaming as part of a larger Tavernier retrospective now available on the Criterion Channel.

Tavernier is best remembered in North America for two dozen disparate, often dazzling, feature films, among them his astonishing debut, The Clockmaker of Saint Paul (1974), the profoundly moving ’Round Midnight (1986), the subtle contemplation A Sunday in the Country (1984), and Dirk Bogarde’s final film (opposite Jane Birkin), Daddy Nostalgia (1990). Tavernier was also an irresistible interview subject, rapturous raconteur, and voracious cinephile, as reflected in his late-career landmark My Journey through French Cinema (2016) and the ten-part television series Journeys through French Cinema (2017–18). With The War with No Name (also known as The Undeclared War), he sought to breathe life into a largely nonexistent national conversation about the blood-soaked military conflict that the French government refused to call a war, in a land that it refused to recognize as a colony. The fighting brought down the fourth French Republic, elicited two attempted military coups, implicated one-time heroes of the resistance in the systematic practice of torture—and in the ruins of its aftermath, in the eyes of most, it was an unpleasant upheaval best forgotten.

Though thirty years old, La Guerre remains a remarkable film—and not only for its evocation of current conflicts, from Gaza to Ukraine.

More here.

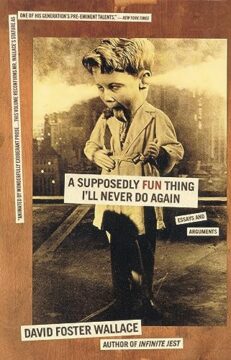

I might’ve stayed away from David Foster Wallace forever were it not for Coco Gauff, whose U.S. Open win last year stirred within me some need to try to fall back in love with tennis—not as a player, but as a literary spectator. Steering clear of the courts, I stuck close to the page, reading what I could of the sport (John McPhee’s

I might’ve stayed away from David Foster Wallace forever were it not for Coco Gauff, whose U.S. Open win last year stirred within me some need to try to fall back in love with tennis—not as a player, but as a literary spectator. Steering clear of the courts, I stuck close to the page, reading what I could of the sport (John McPhee’s

The main thing that I learned in journalism school was that I didn’t belong in journalism school. The other thing I learned was that journalists were deeply anti-intellectual. They were suspicious of ideas; they regarded theories as pretentious; they recoiled at big words (or had never heard of them). For a long time, I had contempt for the profession on that score. In recent years, though, this has yielded to a measure of respect. For notice that I didn’t say that journalists are anti-intellectual. I said they were. Now they’re something else: pseudo-intellectual. And that is much worse.

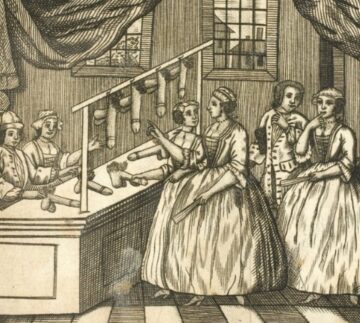

The main thing that I learned in journalism school was that I didn’t belong in journalism school. The other thing I learned was that journalists were deeply anti-intellectual. They were suspicious of ideas; they regarded theories as pretentious; they recoiled at big words (or had never heard of them). For a long time, I had contempt for the profession on that score. In recent years, though, this has yielded to a measure of respect. For notice that I didn’t say that journalists are anti-intellectual. I said they were. Now they’re something else: pseudo-intellectual. And that is much worse. Set out in search of the history of women’s relationship with sex and you will—with a bit of luck—find a very amusing engraving from the seventeenth century lurking in the shallows of the internet. It shows three young women standing at a sales counter.

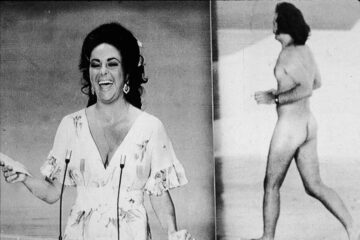

Set out in search of the history of women’s relationship with sex and you will—with a bit of luck—find a very amusing engraving from the seventeenth century lurking in the shallows of the internet. It shows three young women standing at a sales counter. It’s that time of year again. On March 10, stars will gather in Hollywood’s Dolby Theatre to celebrate the best and brightest in filmmaking at the

It’s that time of year again. On March 10, stars will gather in Hollywood’s Dolby Theatre to celebrate the best and brightest in filmmaking at the  I

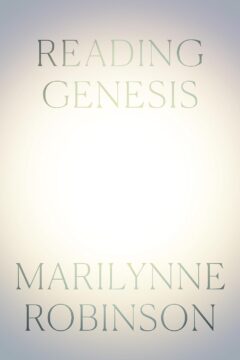

I Robinson illustrates how the ancient Hebrew authors borrowed liberally from the Babylonian mythologies created by their near-east neighbours. But with a crucial distinction. Great narratives such as the

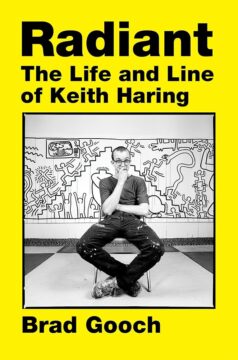

Robinson illustrates how the ancient Hebrew authors borrowed liberally from the Babylonian mythologies created by their near-east neighbours. But with a crucial distinction. Great narratives such as the  Modern art can baffle and intimidate. Keith Haring strove to democratize it.

Modern art can baffle and intimidate. Keith Haring strove to democratize it.