Over at Know Your Enemy:

Category: Archives

No Judgement – pointed views

Houman Barekat in The Guardian:

Lauren Oyler, an American literary critic who writes for Harper’s Magazine and the New Yorker, believes her metier is under threat. “I am a professional, and I am in danger,” she declares in My Perfect Opinions, one of eight previously unpublished essays gathered in her first nonfiction book. She wonders if popular digital platforms such as Goodreads, where users can upload book reviews with minimal editorial filtering, will have long-term ramifications for the more considered, rigorous literary criticism that she gets paid to write. What these online communities lack in intellectual acumen, they make up for in sheer weight of numbers. Are they reshaping literary culture in their own image?

Lauren Oyler, an American literary critic who writes for Harper’s Magazine and the New Yorker, believes her metier is under threat. “I am a professional, and I am in danger,” she declares in My Perfect Opinions, one of eight previously unpublished essays gathered in her first nonfiction book. She wonders if popular digital platforms such as Goodreads, where users can upload book reviews with minimal editorial filtering, will have long-term ramifications for the more considered, rigorous literary criticism that she gets paid to write. What these online communities lack in intellectual acumen, they make up for in sheer weight of numbers. Are they reshaping literary culture in their own image?

The answer seems to be yes. Oyler believes a facile populism has crept into arts and culture commentary in recent years, premised on the notion that, since all taste is ultimately subjective, anything can be as good as anything else – evidenced, for example, in some critics’ insistence that Marvel comics deserve to be treated as serious art. “To reduce appeal to a matter of taste and temperament is the most boring way to be irrefutably correct,” Oyler notes. This tendency, a kind of philistinism dressed up as anti-elitism, lies at the heart of what she calls “today’s crisis in culture criticism”.

More here.

How Much Life Has Ever Existed on Earth, and How Much Ever Will?

Peter Crockford in Singularity Hub:

All organisms are made of living cells. While it is difficult to pinpoint exactly when the first cells came to exist, geologists’ best estimates suggest at least as early as 3.8 billion years ago. But how much life has inhabited this planet since the first cell on Earth? And how much life will ever exist on Earth? In our new study, published in Current Biology, my colleagues from the Weizmann Institute of Science and Smith College and I took aim at these big questions.

All organisms are made of living cells. While it is difficult to pinpoint exactly when the first cells came to exist, geologists’ best estimates suggest at least as early as 3.8 billion years ago. But how much life has inhabited this planet since the first cell on Earth? And how much life will ever exist on Earth? In our new study, published in Current Biology, my colleagues from the Weizmann Institute of Science and Smith College and I took aim at these big questions.

Carbon on Earth

Every year, about 200 billion tons of carbon is taken up through what is known as primary production. During primary production, inorganic carbon—such as carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and bicarbonate in the ocean—is used for energy and to build the organic molecules life needs.

Today, the most notable contributor to this effort is oxygenic photosynthesis, where sunlight and water are key ingredients. However, deciphering past rates of primary production has been a challenging task. In lieu of a time machine, scientists like myself rely on clues left in ancient sedimentary rocks to reconstruct past environments. In the case of primary production, the isotopic composition of oxygen in the form of sulfate in ancient salt deposits allows for such estimates to be made. In our study, we compiled all previous estimates of ancient primary production derived through the method above, as well as many others. The outcome of this productivity census was that we were able to estimate that 100 quintillion (or 100 billion billion) tons of carbon have been through primary production since the origin of life. Big numbers like this are difficult to picture; 100 quintillion tons of carbon is about 100 times the amount of carbon contained within the Earth, a pretty impressive feat for Earth’s primary producers.

More here.

Friday, March 8, 2024

Close-up Photographer of the Year

More here.

Oppenheimer feared nuclear annihilation – and only a chance pause by a Soviet submariner kept it from happening in 1962

Mark Robert Rank in The Conversation:

One of the blockbuster films of the past year, “Oppenheimer,” tells the dramatic story of the development of the atomic bomb and the physicist who headed those efforts, J. Robert Oppenheimer. But despite the Manhattan Project’s success depicted in the film, in his latter years, Oppenheimer became increasingly worried about a nuclear holocaust resulting from the proliferation of these weapons.

One of the blockbuster films of the past year, “Oppenheimer,” tells the dramatic story of the development of the atomic bomb and the physicist who headed those efforts, J. Robert Oppenheimer. But despite the Manhattan Project’s success depicted in the film, in his latter years, Oppenheimer became increasingly worried about a nuclear holocaust resulting from the proliferation of these weapons.

Over the past 80 years, the threat of such nuclear annihilation was perhaps never greater than during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962.

President John F. Kennedy’s secretary of state, Dean Acheson, said that nuclear war was averted during that crisis by “just plain dumb luck.” As I detail in my forthcoming book, “The Random Factor,” nowhere was the influence of chance and luck more evident than on Oct. 27, 1962.

More here.

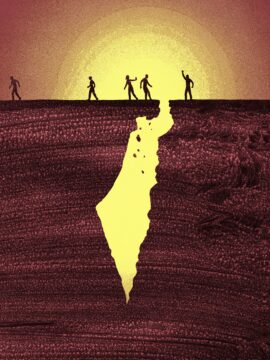

American Jews’ long-standing consensus about Israel has fractured

Aaron Gell in The New Republic:

If anti-Zionist Judaism has long sounded like an oxymoron, chalk it up to two factors: the Shoah, which convinced many Jews that they could never again entrust their welfare to a non-Jewish majority; and a remarkably effective effort by the Zionist establishment to weave the nation-state project into the fabric of Jewish life. But things change: A few days after October 7, I was biking along Brooklyn’s Prospect Park when I came upon a demonstration in front of Senator Chuck Schumer’s apartment building. I’d spent the week absorbed in the news, struggling to take in the immensity and cruelty of the Hamas attack and horrified by the ruthlessness of Israel’s military response. As demonstrators, many carrying signs reading NOT IN MY NAME, marched down the road to Grand Army Plaza, I noticed that some were wearing tallitot and yarmulkes, and I found myself overcome with emotion. This, the first post–October 7 protest by Jewish Voice for Peace—a group I had never even heard of—struck me as a welcome response to what we’d been seeing, and a deeply Jewish one. I ditched my bike and joined the throng.

If anti-Zionist Judaism has long sounded like an oxymoron, chalk it up to two factors: the Shoah, which convinced many Jews that they could never again entrust their welfare to a non-Jewish majority; and a remarkably effective effort by the Zionist establishment to weave the nation-state project into the fabric of Jewish life. But things change: A few days after October 7, I was biking along Brooklyn’s Prospect Park when I came upon a demonstration in front of Senator Chuck Schumer’s apartment building. I’d spent the week absorbed in the news, struggling to take in the immensity and cruelty of the Hamas attack and horrified by the ruthlessness of Israel’s military response. As demonstrators, many carrying signs reading NOT IN MY NAME, marched down the road to Grand Army Plaza, I noticed that some were wearing tallitot and yarmulkes, and I found myself overcome with emotion. This, the first post–October 7 protest by Jewish Voice for Peace—a group I had never even heard of—struck me as a welcome response to what we’d been seeing, and a deeply Jewish one. I ditched my bike and joined the throng.

I mention this in the spirit of full disclosure: I’m hardly an objective observer. I’m a secular Jew, with my own particular set of feelings about Israel—a confusing mix of esteem, curiosity, anguish, and sometimes shame.

More here.

Lata Mangeshkar & Kishore Kumar sing “Jiska Mujhe Tha Intezar” in the 1978 Bollywood Megahit “Don”

Friday Poem

Nero’s Term

Nero was not alarmed when he heard

the prophesy of the Delphic Oracle.

“Let him fear the seventy-three years.”

There was still ample time to enjoy himself.

He is thirty years old. The term

the god allots to him is quite sufficient

for him to prepare for perils to come.

Now he will return to Rome slightly fatigued,

but delightfully fatigued from his journey,

which consisted entirely of days of pleasure

at the theaters, the gardens, the athletic fields . . .

evenings spent in the cities of Greece . . .

Ah the voluptuous delight of nude bodies, above all . . .

Those things Nero thought. And in Spain Galba

secretly assembles and drills his army,

the old man of seventy-three.

by C. P. Cavafy

from The Complete Poems of Cavafy

Harvest Books, 1961

Ambivalence Over AI: We Are All Prometheus Now

Nicholas Dirks in Undark:

REVOLTS AGAINST SCIENCE are often deeply irrational, as we witnessed during the Covid-19 pandemic, with political polarization around lifesaving vaccines and critical public health measures. But public distrust of science has too often been enabled through its manipulation by corporate interests, including big tobacco and oil, as well as by the dangers associated with its use in war.

REVOLTS AGAINST SCIENCE are often deeply irrational, as we witnessed during the Covid-19 pandemic, with political polarization around lifesaving vaccines and critical public health measures. But public distrust of science has too often been enabled through its manipulation by corporate interests, including big tobacco and oil, as well as by the dangers associated with its use in war.

The closing moments of Christopher Nolan’s Academy Award-nominated film “Oppenheimer” — based on the biography “American Prometheus” — depict a fictional scene in which the physicist is speaking with Albert Einstein by a pond at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. Oppenheimer reminds Einstein of the time several years earlier, during the Second World War, when he asked him whether he thought there was any chance that nuclear fission might set off a chain reaction that would destroy the world. Einstein had refused to offer an opinion, and Oppenheimer continued his work to develop the bomb.

Looking wistfully away from Einstein, he says that perhaps it did — that the bomb did set off an uncontrollable chain reaction that would, in the end, destroy the world. These final words give the lie to his hope that such a terrible weapon would stop all wars, an admission of his failure to fully anticipate the political reality of nuclear power.

Oppenheimer’s ambivalence is in a larger sense the story of modern-day science.

More here.

Got milk? Meet the weird amphibian that nurses its young

Freda Kreier in Nature:

An egg-laying amphibian found in Brazil nourishes its newly hatched young with a fatty, milk-like substance, according to a study published today in Science1.

An egg-laying amphibian found in Brazil nourishes its newly hatched young with a fatty, milk-like substance, according to a study published today in Science1.

Lactation is considered a key characteristic of mammals. But a handful of other animals — including birds, fish, insects and even spiders — can produce nutrient-rich liquid for their offspring.

That list also includes caecilians, a group of around 200 limbless, worm-like amphibian species found in tropical regions, most of which live underground and are functionally blind. Around 20 species are known to feed unborn offspring — hatched inside the reproductive system — a type of milk. But the Science study is the first time scientists have described an egg-laying amphibian doing this for offspring hatched outside its body.

The liquid is “functionally similar” to mammalian milk, says study co-author Carlos Jared, a naturalist at the Butantan Institute in São Paulo, Brazil.

More here.

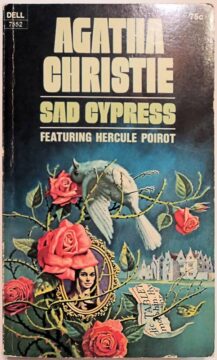

What Do Gardens And Murder Have In Common?

Tim Brinkhof at JSTOR Daily:

Sad Cypress is hardly the only murder mystery to revolve around a flower. As writer and landscape historian Marta McDowell observes in her new book, Gardening Can Be Murder: How Poisonous Poppies, Sinister Shovels, and Grim Gardens Have Inspired Mystery Writers, gardens are popular settings in crime and detective stories, especially those published in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The mysterious people that tend to them also feature commonly in these stories. Sometimes they’re the victims, sometimes the killers, sometimes the unlikely heroes who save the day. Gardens invariably lend setting, motivation, and symbolism. On occasion, as in Sad Cypress, gardening even provides the all-important clues to solving the crime.

Sad Cypress is hardly the only murder mystery to revolve around a flower. As writer and landscape historian Marta McDowell observes in her new book, Gardening Can Be Murder: How Poisonous Poppies, Sinister Shovels, and Grim Gardens Have Inspired Mystery Writers, gardens are popular settings in crime and detective stories, especially those published in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The mysterious people that tend to them also feature commonly in these stories. Sometimes they’re the victims, sometimes the killers, sometimes the unlikely heroes who save the day. Gardens invariably lend setting, motivation, and symbolism. On occasion, as in Sad Cypress, gardening even provides the all-important clues to solving the crime.

Like those clues, the link between homicide and horticulture isn’t obvious. As a literary genre, murder mysteries matured during the Industrial Revolution, when rural villages turned into smog-covered suburbs replete with seedy establishments and dodgy alleyways.

more here.

The End And The Beginning Of The Book

Adam Smyth at the LRB:

Cummings takes ‘book’ in its widest sense – clay tablet, paperback, smartphone, codex, scroll. What is defining about the book is not a particular physical form, but rather the idea, as Cummings nicely puts it, ‘of a text with limits, which can be divided into organised contents’. This inclusivity enables Bibliophobia’s signature trait, which is its rapid vaulting across centuries of mark-making. Take the short span between pages 28 and 35. Cummings notes that in the Heroides, Ovid’s rewriting of Homer’s Odyssey, Penelope writes Ulysses a letter, saying don’t write back, just come. This relationship between writing and presence takes us from the web of Penelope to the web of Tim Berners-Lee and Shoshana Zuboff’s theory of the ‘two texts’ of digital media: the search we type in on Google produces a mirror image in the form of a record of the searcher. And then, via Aristotle’s De interpretatione and Voltaire’s Dictionnaire philosophique on writing’s relationship to speech, we’re on to the Greek and Roman alphabets and the relationship between inscriptions in stone and state power, and Freud’s theory of the double (‘an insurance against the extinction of the self’). At moments along the way, Cummings might provide a breathless history of alphabets or Islamic calligraphy.

Cummings takes ‘book’ in its widest sense – clay tablet, paperback, smartphone, codex, scroll. What is defining about the book is not a particular physical form, but rather the idea, as Cummings nicely puts it, ‘of a text with limits, which can be divided into organised contents’. This inclusivity enables Bibliophobia’s signature trait, which is its rapid vaulting across centuries of mark-making. Take the short span between pages 28 and 35. Cummings notes that in the Heroides, Ovid’s rewriting of Homer’s Odyssey, Penelope writes Ulysses a letter, saying don’t write back, just come. This relationship between writing and presence takes us from the web of Penelope to the web of Tim Berners-Lee and Shoshana Zuboff’s theory of the ‘two texts’ of digital media: the search we type in on Google produces a mirror image in the form of a record of the searcher. And then, via Aristotle’s De interpretatione and Voltaire’s Dictionnaire philosophique on writing’s relationship to speech, we’re on to the Greek and Roman alphabets and the relationship between inscriptions in stone and state power, and Freud’s theory of the double (‘an insurance against the extinction of the self’). At moments along the way, Cummings might provide a breathless history of alphabets or Islamic calligraphy.

more here.

Yann Lecun: Meta AI, Open Source, Limits of LLMs, AGI & the Future of AI

Thursday, March 7, 2024

Gregory Murphy on the Psychology of Categories

The Editors of the MIT Press Reader:

Despite the vast diversity and individuality in every life, we seek patterns, organization, and control. Or, as cognitive psychologist Gregory Murphy puts it: “We put an awful lot of effort into trying to figure out and convince others of just what kind of person someone is, what kind of action something was, and even what kind of object something is.”

Despite the vast diversity and individuality in every life, we seek patterns, organization, and control. Or, as cognitive psychologist Gregory Murphy puts it: “We put an awful lot of effort into trying to figure out and convince others of just what kind of person someone is, what kind of action something was, and even what kind of object something is.”

In his new book “Categories We Live By,” Murphy, a professor emeritus at New York University who has spent a career studying concepts and categories, considers the categories we create to manage life’s sprawling diversity. Analyzing everything from bureaucracy’s innumerable categorizations to the minutiae of language, his book reveals how these categories are imposed on us and how that imposition affects our everyday lives.

In the interview that follows, Murphy discusses his lifelong interest in studying concepts and categories — “the glue that holds our mental world together,” as he’s described them — the impact of his research on his worldview, and the complex relationship between language and categorization across cultures.

More here.

The Replication Bomb

Richard Dawkins in The Poetry of Reality:

In our galaxy of a hundred billion stars, only three supernovas have been recorded by astronomers: in 1054, in 1572, and in 1604. The Crab Nebula is the remains of the event of 1054, recorded by Chinese astronomers. (When I say the event “of 1054” I mean, of course, the event of which news reached Earth in 1054. The event itself took place six thousand years earlier. The wave-front of light from it hit us in 1054.) Since 1604, the only supernovas that have been seen have been in other galaxies.

In our galaxy of a hundred billion stars, only three supernovas have been recorded by astronomers: in 1054, in 1572, and in 1604. The Crab Nebula is the remains of the event of 1054, recorded by Chinese astronomers. (When I say the event “of 1054” I mean, of course, the event of which news reached Earth in 1054. The event itself took place six thousand years earlier. The wave-front of light from it hit us in 1054.) Since 1604, the only supernovas that have been seen have been in other galaxies.

There is another type of explosion a star can sustain. Instead of “going supernova” it “goes information.” The explosion begins more slowly than a supernova and takes incomparably longer to build up. We can call it an information bomb or, for reasons that will become apparent, a replication bomb. For the first few billion years of its build-up, you could detect a replication bomb only if you were in the immediate vicinity. Eventually, subtle manifestations of the explosion begin to leak away into more distant regions of space and it becomes, at least potentially, detectable from a long way away. We do not know how this kind of explosion ends. Presumably it eventually fades away like a supernova, but we do not know how far it typically builds up first. Perhaps to a violent and self-destructive catastrophe. Perhaps to a more gentle and repeated emission of objects,moving, in a guided rather than a simple ballistic trajectory, away from the star into distant reaches of space, where it may infect other star systems with the same tendency to explode.

More here.

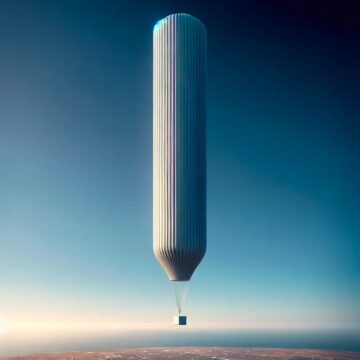

How You Can Easily Delay Climate Change Today: SO2 Injection

Tomas Pueyo in Uncharted Territories:

In We Can Already Stop Climate Change If We Want To, I explained that we have a path to solve climate change (renewables, nuclear, batteries, olivine weathering), but it will take at least a few decades to get there. In the meantime, CO2 emissions will keep growing, there’s nothing we can do to reverse them fast enough, and global temperatures will keep increasing.

In We Can Already Stop Climate Change If We Want To, I explained that we have a path to solve climate change (renewables, nuclear, batteries, olivine weathering), but it will take at least a few decades to get there. In the meantime, CO2 emissions will keep growing, there’s nothing we can do to reverse them fast enough, and global temperatures will keep increasing.

There is only one thing we can do to avoid these potentially catastrophic consequences: Cooling the Earth artificially until we get CO2 levels in hand. And the best way we know to do that is sending SO2 to the stratosphere.

I outlined that solution in the article linked above, but I didn’t go in depth, and many of you had questions:

Does it really work? How?

Is this really the best solution? What are the alternatives?

How safe is it? What are the downsides?

Will states allow this? Is it legal?

How much will it cost?

Where should we release this SO2?

So I dove into this, talked with the only company that I know that is trying to do this at scale, and as a result of this deep dive, I am trying to invest in the company. Here’s what I found…

More here.

Andrew Ng on AI’s Potential Effect on the Labor Force

Caribbean Mountain frogs that taste like chicken born at London Zoo

Jacob Evans in BBC:

Six froglets of one of the world’s most threatened frog species have been born at London Zoo.

Six froglets of one of the world’s most threatened frog species have been born at London Zoo.

The arrival of the new Mountain chicken frogs has been heralded by conservationists, who estimate that just 20 frogs remain in the wild. Originally from the Caribbean, jumbo frogs are a local delicacy supposedly tasting like chicken and can reach up to 1kg (2lbs) – hence the name. An invasive fungus and continued habitat loss has ravaged the species. Zookeepers had suspicions offspring were on their way after the resident male Mountain chicken started digging a ‘bowl’ in the newly-built enclosure – in an attempt to entice his female counterpart.

His efforts paid dividends and shortly after a foam nest was created, where the tadpoles developed. During this period, the female frog feeds the tadpoles by producing infertile eggs until the tadpoles metamorphose. Mother mountain chicken frogs may feed their tadpoles 10-13 times during their development, meaning she may produce an estimated 10,000-25,000 eggs. Soon after the zoo welcomed six froglets to their colony.

Two females had been living together before a male was introduced in November and the births were the first Mountain chickens to be born at the zoo for five years.

More here.

Study raises questions about plastic pollution’s effect on heart health

From Phys.Org:

We breathe, eat and drink tiny particles of plastic. But are these minuscule specks in the body harmless, dangerous or somewhere in between?

We breathe, eat and drink tiny particles of plastic. But are these minuscule specks in the body harmless, dangerous or somewhere in between?

A small study published Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine raises more questions than it answers about how these bits—microplastics and the smaller nanoplastics—might affect the heart. The Italian study has weaknesses, but is likely to draw attention to the debate over the problem of plastic pollution. Most plastic waste is never recycled and breaks down into these particles. “The study is intriguing. However, there are really substantial limitations,” said Dr. Steve Nissen, a heart expert at the Cleveland Clinic. “It’s a wake-up call that perhaps we need to take the problem of microplastics more seriously. As a cause for heart disease? Not proven. As a potential cause? Yes, maybe.” WHAT DID THE STUDY FIND?

The study involved 257 people who had surgery to clear blocked blood vessels in their necks. Italian researchers analyzed the fatty buildup that the surgeons removed from the carotid arteries, which supply blood and oxygen to the brain. Using two methods, they found evidence of plastics—mostly invisible nanoplastics—in the artery plaque of 150 patients and no evidence of plastics in 107 patients. They followed these people for three years. During that time, 30 or 20% of those with plastics had a heart attack, stroke or died from any cause, compared to eight or about 8% of those with no evidence of plastics.

More here.