David Byrne in Reasons to be Cheerful:

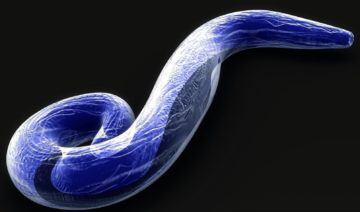

At the end of June, the World Health Organization certified China as having eliminated malaria. The announcement may have gotten a little drowned out by the mass spectacles surrounding the Communist Party’s 100th birthday, but make no mistake: going from 30 million cases annually to zero really is a reason to be cheerful.

At the end of June, the World Health Organization certified China as having eliminated malaria. The announcement may have gotten a little drowned out by the mass spectacles surrounding the Communist Party’s 100th birthday, but make no mistake: going from 30 million cases annually to zero really is a reason to be cheerful.

There are a lot of places that would like to emulate China — malaria is one of the top public health threats around the world, with 200 million cases and 400,000 deaths per year. And while a number of other countries are malaria-free — most recently El Salvador, Algeria, Argentina, Paraguay and Uzbekistan — many more are eager to know how the Chinese did it.

The scope of China’s achievement is hard to overstate.

More here.

Steven Weinberg and I knew each other for seventy-four of our eighty-eight years. He was my friend and classmate throughout high school and college. We met at the Bronx High School of Science, where, together with Gerald Feinberg, Morton Sternheim, and Menasha Tausner, we decided to become theoretical physicists—as we all became.

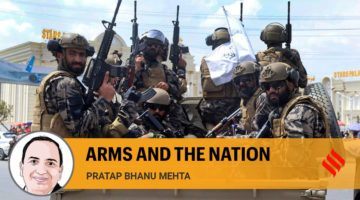

Steven Weinberg and I knew each other for seventy-four of our eighty-eight years. He was my friend and classmate throughout high school and college. We met at the Bronx High School of Science, where, together with Gerald Feinberg, Morton Sternheim, and Menasha Tausner, we decided to become theoretical physicists—as we all became. There is an old adage that if you want to understand state building or state breakdown, follow the guns. In conflict zones like Afghanistan, it is all too easy to take recourse to debates over development and culture, while ignoring the dynamics of armed conflict, and the presence of weaponry that militarises society and embeds violence. Even a casual perusal of databases at Small Arms Survey, Geneva, that tracks violent conflict and the proliferation of arms, brings home some basic facts about state building and violence.

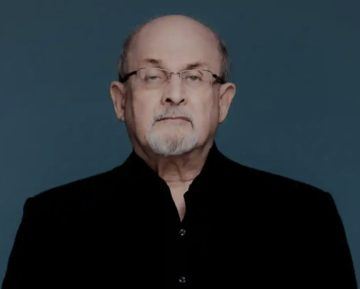

There is an old adage that if you want to understand state building or state breakdown, follow the guns. In conflict zones like Afghanistan, it is all too easy to take recourse to debates over development and culture, while ignoring the dynamics of armed conflict, and the presence of weaponry that militarises society and embeds violence. Even a casual perusal of databases at Small Arms Survey, Geneva, that tracks violent conflict and the proliferation of arms, brings home some basic facts about state building and violence. Out of the gloom Salman Rushdie floats into view, his familiar face with short beard and glasses hovering on screen in front of a library that should win any competition for the most impressive Zoom bookshelf backdrop.

Out of the gloom Salman Rushdie floats into view, his familiar face with short beard and glasses hovering on screen in front of a library that should win any competition for the most impressive Zoom bookshelf backdrop. There is no general theory of problem-solving, or even a reliable set of principles that will usually work. It’s therefore interesting to see how our brains actually go about solving problems. Here’s an interesting feature that you might not have guessed: when faced with an imperfect situation, our first move to improve it tends to involve adding new elements, rather than taking away. We are, in general, resistant to subtractive change. Leidy Klotz is an engineer and designer who has worked with psychologists and neuroscientists to study this phenomenon. We talk about how our relative blindness to subtractive possibilities manifests itself, and what lessons might be for design more generally.

There is no general theory of problem-solving, or even a reliable set of principles that will usually work. It’s therefore interesting to see how our brains actually go about solving problems. Here’s an interesting feature that you might not have guessed: when faced with an imperfect situation, our first move to improve it tends to involve adding new elements, rather than taking away. We are, in general, resistant to subtractive change. Leidy Klotz is an engineer and designer who has worked with psychologists and neuroscientists to study this phenomenon. We talk about how our relative blindness to subtractive possibilities manifests itself, and what lessons might be for design more generally. Could admitting millions more immigrants over the next decade be the jolt the U.S. needs to revive its economy, culture, and politics? After four years of restrictionism under President Trump, ongoing border controversies, and an escalating culture war led by nativists, this idea may seem counterintuitive or even far-fetched. But recent labor market trends, demographic changes, and even accelerating climate change all point to dramatically increased immigration as a logical catalyst for national renewal. Becoming the most welcoming country on Earth for migrants—breathing new life into our most flattering, if too often inaccurate self-image—could be our salvation.

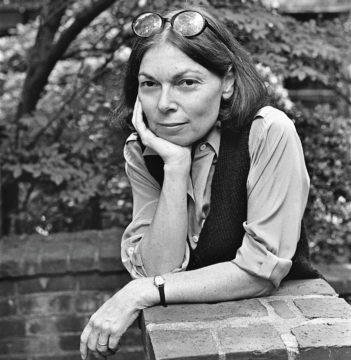

Could admitting millions more immigrants over the next decade be the jolt the U.S. needs to revive its economy, culture, and politics? After four years of restrictionism under President Trump, ongoing border controversies, and an escalating culture war led by nativists, this idea may seem counterintuitive or even far-fetched. But recent labor market trends, demographic changes, and even accelerating climate change all point to dramatically increased immigration as a logical catalyst for national renewal. Becoming the most welcoming country on Earth for migrants—breathing new life into our most flattering, if too often inaccurate self-image—could be our salvation. One of Janet’s themes as a writer was self-delusion in all its guises—the propensity we all share for telling ourselves stories that, at the very least, reconfigure events to cast ourselves in a more favorable light. I was stung by one line in the profile: that (I paraphrase) in all our time together, nothing I said about my work was of the slightest interest to her. Once my vanity recovered from the dismissal of my “thinking,” the veracity of Janet’s verdict was clear. (The passage continued to insist that nothing any artist ever says about their work is of interest.) I eventually came to feel more or less the same way—that nothing anybody says about their intentions or “process” is of any particular relevance unless it’s a one-liner by de Kooning. Who cares? This attitude is at odds with the prevailing reverence for that peculiar literary artifact, the artist’s statement, but such was the incontrovertible nature of Janet’s contrarianism. Like any good analyst, she was only interested in the story behind the story. The fact that a belief is widely held should be enough to raise our suspicions.

One of Janet’s themes as a writer was self-delusion in all its guises—the propensity we all share for telling ourselves stories that, at the very least, reconfigure events to cast ourselves in a more favorable light. I was stung by one line in the profile: that (I paraphrase) in all our time together, nothing I said about my work was of the slightest interest to her. Once my vanity recovered from the dismissal of my “thinking,” the veracity of Janet’s verdict was clear. (The passage continued to insist that nothing any artist ever says about their work is of interest.) I eventually came to feel more or less the same way—that nothing anybody says about their intentions or “process” is of any particular relevance unless it’s a one-liner by de Kooning. Who cares? This attitude is at odds with the prevailing reverence for that peculiar literary artifact, the artist’s statement, but such was the incontrovertible nature of Janet’s contrarianism. Like any good analyst, she was only interested in the story behind the story. The fact that a belief is widely held should be enough to raise our suspicions. It seemed like a good idea to avoid the screen, but my resolve didn’t last long. The book I was reading at the time, On the Natural History of Destruction, a collection of W. G. Sebald’s lectures and essays about the literature of the Second World War, concludes with a piece on the German-Swedish writer Peter Weiss. Like most English-speakers who had heard of him, I knew of Weiss only as the author of the play The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade (Marat/Sade for short), which had been made into a film starring Patrick Magee and Glenda Jackson during the brief vogue for interwar European aesthetic programs—in this case Brecht’s Epic Theater and Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty—among the countercultures of Britain and the United States in the 1960s. Sebald, however, mentions Marat/Sade only in passing. Instead, he discusses Weiss’s early career as a painter; his surreal autobiographical novella, Leavetaking; his controversial documentary play about the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, The Investigation; and, at greatest length, his late three-volume novel about the German anti-fascist underground, The Aesthetics of Resistance.

It seemed like a good idea to avoid the screen, but my resolve didn’t last long. The book I was reading at the time, On the Natural History of Destruction, a collection of W. G. Sebald’s lectures and essays about the literature of the Second World War, concludes with a piece on the German-Swedish writer Peter Weiss. Like most English-speakers who had heard of him, I knew of Weiss only as the author of the play The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade (Marat/Sade for short), which had been made into a film starring Patrick Magee and Glenda Jackson during the brief vogue for interwar European aesthetic programs—in this case Brecht’s Epic Theater and Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty—among the countercultures of Britain and the United States in the 1960s. Sebald, however, mentions Marat/Sade only in passing. Instead, he discusses Weiss’s early career as a painter; his surreal autobiographical novella, Leavetaking; his controversial documentary play about the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, The Investigation; and, at greatest length, his late three-volume novel about the German anti-fascist underground, The Aesthetics of Resistance. Last month, when Samina Farooq, a domestic worker, learned that a fellow female worker in Lahore had been beaten by her employer for spilling milk on the floor, she went to see her. Her message: You should quit now. “Bibis [female employers] beat us for dropping milk on the floor or deduct a portion of our salary if we mistakenly burn a piece of cloth when ironing. Are we not humans? Can’t we make mistakes?” says Ms. Farooq. After the employer acknowledged that she had treated her maid unfairly, the maid agreed to stay on. The International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates that Pakistan has more than 8.5 million domestic workers, mostly women and children. Some suffer appalling abuse at the hands of their employers. Last year an

Last month, when Samina Farooq, a domestic worker, learned that a fellow female worker in Lahore had been beaten by her employer for spilling milk on the floor, she went to see her. Her message: You should quit now. “Bibis [female employers] beat us for dropping milk on the floor or deduct a portion of our salary if we mistakenly burn a piece of cloth when ironing. Are we not humans? Can’t we make mistakes?” says Ms. Farooq. After the employer acknowledged that she had treated her maid unfairly, the maid agreed to stay on. The International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates that Pakistan has more than 8.5 million domestic workers, mostly women and children. Some suffer appalling abuse at the hands of their employers. Last year an  T

T In one sentence, then, here’s my beef with The Chair: its script portrays a mob, step by step, destroying an innocent man’s life over nothing, and yet it wants me to feel the mob’s pain, and be disappointed in its victim for mulishly insisting on his innocence (even though he is, in fact, innocent).

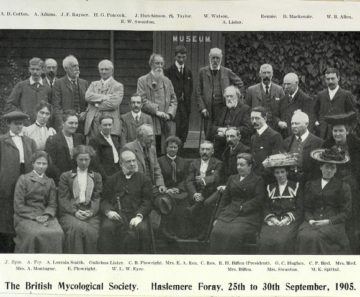

In one sentence, then, here’s my beef with The Chair: its script portrays a mob, step by step, destroying an innocent man’s life over nothing, and yet it wants me to feel the mob’s pain, and be disappointed in its victim for mulishly insisting on his innocence (even though he is, in fact, innocent). The pioneer of slime mould research was an extraordinary mycologist called Gulielma Lister (1860-1949). Like many female scientists, she has vanished into near obscurity, yet her colleagues celebrated her as the “Queen of Slime Moulds.” In 1905, she was among the first 25 women admitted as a Fellow of London’s prestigious Linnean Society. She made quite an impression on that august group: one younger admirer remembered that she “removed her hat in deference to the sexless character of a Fellow. It was an unusual thing then for a lady to remove her hat, but we all took our cue from Miss Lister and did the same.” She broke the conventions of her time, and a century later her research lies behind a major new approach to computer software.

The pioneer of slime mould research was an extraordinary mycologist called Gulielma Lister (1860-1949). Like many female scientists, she has vanished into near obscurity, yet her colleagues celebrated her as the “Queen of Slime Moulds.” In 1905, she was among the first 25 women admitted as a Fellow of London’s prestigious Linnean Society. She made quite an impression on that august group: one younger admirer remembered that she “removed her hat in deference to the sexless character of a Fellow. It was an unusual thing then for a lady to remove her hat, but we all took our cue from Miss Lister and did the same.” She broke the conventions of her time, and a century later her research lies behind a major new approach to computer software.