George Makari at Literary Hub:

George Makari: I heard you say in an interview that as you’re starting to think about writing a book, you write a note to yourself, saying, “Write a book that no one else could write.”

Geoff Dyer: Yeah, it’s a little piece of self-encouragement. Because, you know, sometimes I’m sort of worried about my take on a given subject. Do I know enough about it? Take for example, my history of photography called The Ongoing Moment. I wrote that book because I wanted to find out about the history of photography. I wrote the book for the same reason that readers might later go to it.

Geoff Dyer: Yeah, it’s a little piece of self-encouragement. Because, you know, sometimes I’m sort of worried about my take on a given subject. Do I know enough about it? Take for example, my history of photography called The Ongoing Moment. I wrote that book because I wanted to find out about the history of photography. I wrote the book for the same reason that readers might later go to it.

I think one of the features of nonfiction today is that, to a degree, a book could be written by anyone possessed of a certain level of knowledge. The area of expertise might change, but quite often, there’s nothing particularly distinct about the writing or the thought. With my books, for good or ill, they could only be written by me.

More here.

Granted, the social lives of viruses aren’t quite like those of other species. Viruses don’t post selfies to social media, volunteer at food banks or commit identity theft like humans do. They don’t fight with allies to dominate a troop like baboons; they don’t collect nectar to feed their queen like honeybees; they don’t even congeal into slimy mats for their common defense like some bacteria do. Nevertheless, sociovirologists believe that viruses do

Granted, the social lives of viruses aren’t quite like those of other species. Viruses don’t post selfies to social media, volunteer at food banks or commit identity theft like humans do. They don’t fight with allies to dominate a troop like baboons; they don’t collect nectar to feed their queen like honeybees; they don’t even congeal into slimy mats for their common defense like some bacteria do. Nevertheless, sociovirologists believe that viruses do  Saar Wilf is an ex-Israeli entrepreneur. Since 2016, he’s been developing a new form of reasoning, meant to transcend normal human bias.

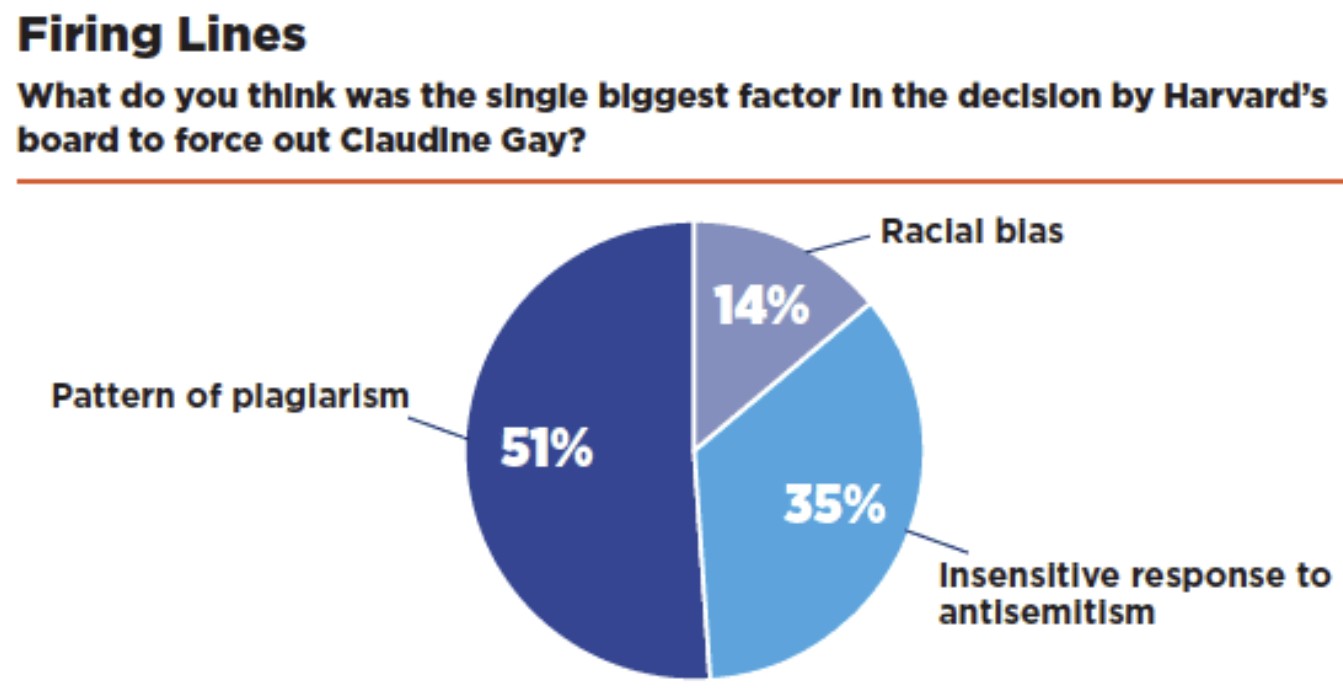

Saar Wilf is an ex-Israeli entrepreneur. Since 2016, he’s been developing a new form of reasoning, meant to transcend normal human bias. The negative buzz over board challenges experienced by Harvard, Tesla and Boeing shows remarkably parallel problems over the same period. Harvard’s stumble is particularly educational for boards facing a governance crisis.

The negative buzz over board challenges experienced by Harvard, Tesla and Boeing shows remarkably parallel problems over the same period. Harvard’s stumble is particularly educational for boards facing a governance crisis. I

I Come with me, down the rabbit hole that is the life and work of the Brooklyn-born poet Delmore Schwartz (1913-66). There are two primary portals into Delmore World. Neither involves his own verse. Reading about Schwartz is more invigorating than reading him, or so I have long thought. He was so intense and unbuttoned that he inspired two of the best books of the second half of the 20th century.

Come with me, down the rabbit hole that is the life and work of the Brooklyn-born poet Delmore Schwartz (1913-66). There are two primary portals into Delmore World. Neither involves his own verse. Reading about Schwartz is more invigorating than reading him, or so I have long thought. He was so intense and unbuttoned that he inspired two of the best books of the second half of the 20th century. Several years ago, I fell at the gym and ripped two tendons in my wrist. The pain was excruciating, and within minutes my hand had swollen grotesquely and become hot to the touch. I was reminded of a patient I’d seen early in medical school, whose bacterial infection extended from his knee to his toes. Latin was long absent from the teaching curriculum, but, as my instructor examined the leg, he cited the four classic symptoms of inflammation articulated by the Roman medical writer Celsus in the first century: rubor, redness; tumor, swelling; calor, heat; and dolor, pain. In Latin, inflammatio means “setting on fire,” and as I considered the searing pain in my injured hand I understood how the condition earned its name.

Several years ago, I fell at the gym and ripped two tendons in my wrist. The pain was excruciating, and within minutes my hand had swollen grotesquely and become hot to the touch. I was reminded of a patient I’d seen early in medical school, whose bacterial infection extended from his knee to his toes. Latin was long absent from the teaching curriculum, but, as my instructor examined the leg, he cited the four classic symptoms of inflammation articulated by the Roman medical writer Celsus in the first century: rubor, redness; tumor, swelling; calor, heat; and dolor, pain. In Latin, inflammatio means “setting on fire,” and as I considered the searing pain in my injured hand I understood how the condition earned its name. In 2008, the biotech industry

In 2008, the biotech industry My first impression, upon opening Hollis’s The Waste Land: A Biography of a Poem was admittedly delicious. A usual kind of epigraph greets us: “There is always another one walking beside you,” from Eliot’s poem, but then we turn the page, and on the back of the epigraph page is a quotation from Eliot, a meaty paragraph, and facing it, on the right-hand side, is a shorter passage from Pound. Right away, then, the two men are side by side, in the opening pages in a way that disrupts the usual front page material of a tome. It is a nice touch that not only forecasts the book’s focus on the relationship between the two men in the crafting of one of the inarguably influential English language poems of the twentieth century but also indicates the attention to detail and summoning of atmosphere that characterize the bulk of Hollis’s project, if not its achievement. Which is this: to demythologize, and at times painfully, re-animate the gross disturbances in Eliot’s life and character that, for better or worse, have bequeathed us the still-jarring title poem.

My first impression, upon opening Hollis’s The Waste Land: A Biography of a Poem was admittedly delicious. A usual kind of epigraph greets us: “There is always another one walking beside you,” from Eliot’s poem, but then we turn the page, and on the back of the epigraph page is a quotation from Eliot, a meaty paragraph, and facing it, on the right-hand side, is a shorter passage from Pound. Right away, then, the two men are side by side, in the opening pages in a way that disrupts the usual front page material of a tome. It is a nice touch that not only forecasts the book’s focus on the relationship between the two men in the crafting of one of the inarguably influential English language poems of the twentieth century but also indicates the attention to detail and summoning of atmosphere that characterize the bulk of Hollis’s project, if not its achievement. Which is this: to demythologize, and at times painfully, re-animate the gross disturbances in Eliot’s life and character that, for better or worse, have bequeathed us the still-jarring title poem. Claude Shannon can’t sit still. We’re in the living room of his home north of Boston, an edifice called Entropy House, and I’m trying to get him to recall how he came up with information theory. Shannon, who is a boyish 73, with a shy grin and snowy hair, is tired of dwelling on his past. He wants to show me his gadgets.

Claude Shannon can’t sit still. We’re in the living room of his home north of Boston, an edifice called Entropy House, and I’m trying to get him to recall how he came up with information theory. Shannon, who is a boyish 73, with a shy grin and snowy hair, is tired of dwelling on his past. He wants to show me his gadgets.