Jonathan Haidt at the Heterodox Academy:

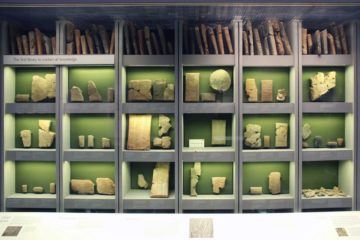

In September 2016 I gave a lecture at Duke University: “Two Incompatible Sacred Values in American Universities.” I suggested that the ancient Greek word telos was helpful for understanding the rapid cultural change going on at America’s top universities that began in the fall of 2015. Telos means “the end, goal, or purpose for which an act is done, or at which a profession or institution aims.” The telos of a knife is to cut, the telos of medicine is to heal, and the telos of a university is truth, I suggested. The word (or close cognates) appears on many university crests, and our practices and norms — some stretching back to Plato’s academy — only make sense if you see a university as an institution organized to help scholars get closer to truth using the particular methods of their field.¹

In September 2016 I gave a lecture at Duke University: “Two Incompatible Sacred Values in American Universities.” I suggested that the ancient Greek word telos was helpful for understanding the rapid cultural change going on at America’s top universities that began in the fall of 2015. Telos means “the end, goal, or purpose for which an act is done, or at which a profession or institution aims.” The telos of a knife is to cut, the telos of medicine is to heal, and the telos of a university is truth, I suggested. The word (or close cognates) appears on many university crests, and our practices and norms — some stretching back to Plato’s academy — only make sense if you see a university as an institution organized to help scholars get closer to truth using the particular methods of their field.¹

I said that universities can have many goals (such as fiscal health and successful sports teams) and many values (such as social justice, national service, or Christian humility), but they can have only one telos, because a telos is like a North Star. It is the end, purpose, or goal around which the institution is structured. An institution can rotate on one axis only. If it tries to elevate a second goal or value to the status of a telos, it is like trying to get a spinning top or rotating solar system to simultaneously rotate around two axes. I argued that the sudden wave of protests and changes that were sweeping through universities were attempts to elevate the value of social justice to become a second telos, which would require a massive restructuring of universities and their norms in ways that damaged their ability to find truth.

More here.

Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman, died on September 16th in Tehran after being detained and allegedly beaten by Iran’s

Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman, died on September 16th in Tehran after being detained and allegedly beaten by Iran’s  The first therapeutic cancer vaccine, approved more than a decade ago, targeted prostate tumours. The treatment involves extracting antigen-presenting cells — a component of the immune system that tells other cells what to target — from a person’s blood, loading them with a marker found on prostate tumours, and then returning them to the patient. The idea is that other immune cells will then take note and attack the cancer.

The first therapeutic cancer vaccine, approved more than a decade ago, targeted prostate tumours. The treatment involves extracting antigen-presenting cells — a component of the immune system that tells other cells what to target — from a person’s blood, loading them with a marker found on prostate tumours, and then returning them to the patient. The idea is that other immune cells will then take note and attack the cancer. The signaling behavior of human beings is intricate indeed. Forty years ago a man, seething with desire, issued forth a string of identical second-person singular imperatives followed by a hortatory first-person plural:

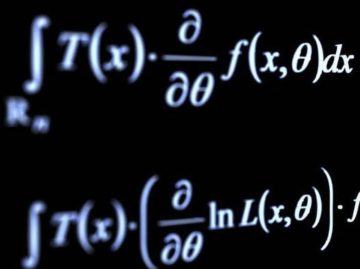

The signaling behavior of human beings is intricate indeed. Forty years ago a man, seething with desire, issued forth a string of identical second-person singular imperatives followed by a hortatory first-person plural: The aim of my piece was to challenge the popular notion that mathematics is synonymous with calculation. Starting with arithmetic and proceeding through algebra and beyond, the message drummed into our heads as students is that we do math to “get the right answer.” The drill of multiplication tables, the drudgery of long division, the quadratic formula and its memorization—these are the dreary memories many of us carry around from school as a result.

The aim of my piece was to challenge the popular notion that mathematics is synonymous with calculation. Starting with arithmetic and proceeding through algebra and beyond, the message drummed into our heads as students is that we do math to “get the right answer.” The drill of multiplication tables, the drudgery of long division, the quadratic formula and its memorization—these are the dreary memories many of us carry around from school as a result. The recent debate over “presentism” among historians, especially those based in the United States, has generated both heat and light. It is a useful conversation to have now, at a moment when the public sphere, and even more so the university’s space within it, seems to consist more of mines than of fields. Debates about Covid-19, affirmative (in)action, antisemitism, sexual violence, student debt, Title IX, Confederate monuments, racist donors, resigning presidents, and rogue trustees combine to occlude the daylight of classes, books, and learning.

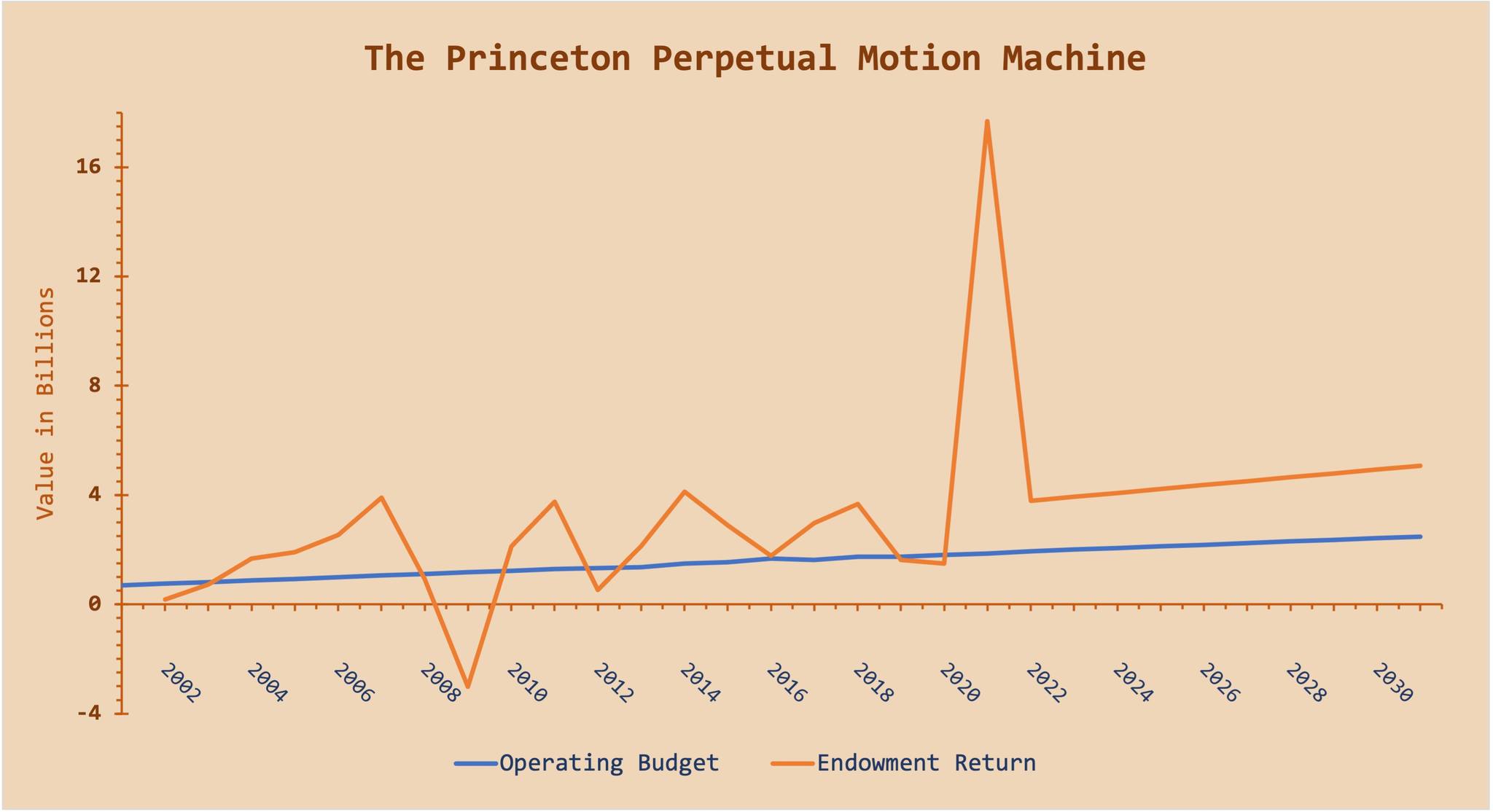

The recent debate over “presentism” among historians, especially those based in the United States, has generated both heat and light. It is a useful conversation to have now, at a moment when the public sphere, and even more so the university’s space within it, seems to consist more of mines than of fields. Debates about Covid-19, affirmative (in)action, antisemitism, sexual violence, student debt, Title IX, Confederate monuments, racist donors, resigning presidents, and rogue trustees combine to occlude the daylight of classes, books, and learning. After a stellar year in 2021, Princeton University has an endowment of $37.7 billion. Over the past 20 years, the average annual return for the endowment has been 11.2 percent. Let us give Princeton the benefit of the doubt and assume that at least some of that was luck and maybe unsustainable, and that a more reasonable prediction going forward would be that Princeton can average a return on its investments of an even 10 percent a year. That puts Princeton’s endowment return next year at roughly $3.77 billion.

After a stellar year in 2021, Princeton University has an endowment of $37.7 billion. Over the past 20 years, the average annual return for the endowment has been 11.2 percent. Let us give Princeton the benefit of the doubt and assume that at least some of that was luck and maybe unsustainable, and that a more reasonable prediction going forward would be that Princeton can average a return on its investments of an even 10 percent a year. That puts Princeton’s endowment return next year at roughly $3.77 billion. “D

“D Zan, Zendegi, Azadi: Woman! Life! Freedom!

Zan, Zendegi, Azadi: Woman! Life! Freedom! Alden Young in Phenomenal World:

Alden Young in Phenomenal World: Stephen Ornes in Quanta:

Stephen Ornes in Quanta: Kahled Talaat in Tablet (photo by Stefan Sauer/Picture Alliance via Getty Images)

Kahled Talaat in Tablet (photo by Stefan Sauer/Picture Alliance via Getty Images) His fingernails are ragged. He wears designer suits but his choice of underwear, cheap Russian tighty-whities, is poignant. When he gets drunk, he talks about Stalin. He likes the dumbest game shows. Maybe he’s K.G.B. He does not know how to unfasten garters.

His fingernails are ragged. He wears designer suits but his choice of underwear, cheap Russian tighty-whities, is poignant. When he gets drunk, he talks about Stalin. He likes the dumbest game shows. Maybe he’s K.G.B. He does not know how to unfasten garters. How to walk properly, according to Lorraine O’Grady, the eighty-eight-year-old conceptual and performance artist: “With your chin tucked under your head, your shoulders dropped down, your stomach pulled up.” Good posture has become a concern for O’Grady in the past couple of years, as her latest persona, the Knight, is a character that requires her to wear a forty-pound suit of armor. “As long as I don’t gain or lose more than three or four pounds, I’m O.K.,” O’Grady told me in late August, over Zoom, while we discussed “Greetings and Theses,” the fourteen-minute film that constituted the official performance début of the Knight. The première was held, in late July, at the Brooklyn Museum, the site of the 2021 exhibition “

How to walk properly, according to Lorraine O’Grady, the eighty-eight-year-old conceptual and performance artist: “With your chin tucked under your head, your shoulders dropped down, your stomach pulled up.” Good posture has become a concern for O’Grady in the past couple of years, as her latest persona, the Knight, is a character that requires her to wear a forty-pound suit of armor. “As long as I don’t gain or lose more than three or four pounds, I’m O.K.,” O’Grady told me in late August, over Zoom, while we discussed “Greetings and Theses,” the fourteen-minute film that constituted the official performance début of the Knight. The première was held, in late July, at the Brooklyn Museum, the site of the 2021 exhibition “