David Kordahl at The New Atlantis:

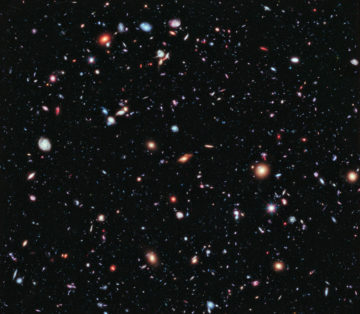

Why was the direction of cosmology altered so decisively when two radio engineers observed the cosmic microwave background? It wasn’t because of just one thing. The “hot big bang” scenario predicted the cosmic microwave background, since matter and light were presumed to be in thermal equilibrium at the beginning. As the universe expanded and cooled, the matter was thought to clump together gravitationally, becoming stars and galaxies, while the light was thought to zip around diffusely, becoming the cosmic microwave background. But the hot big bang also solved other problems. Steady-state theorists posited that hydrogen was being created ex nihilo, while heavier elements could be forged by nuclear fusion in the stars. But their numbers didn’t work out. Steady-state theorists found that helium was more abundant in stars than stellar fusion alone would predict. But in a hot big bang, hydrogen could also be fused into helium at the very beginning.

more here.

Though never a household name, Bruce Duffy drew rapturous critical praise for his 1987 debut novel,

Though never a household name, Bruce Duffy drew rapturous critical praise for his 1987 debut novel,  This past spring, the philosopher Richard J. Bernstein taught his final two classes at the New School for Social Research, in New York, where he had been a professor since 1989. One was a course on American pragmatism, the tradition to which his own work belongs. The other was a seminar on

This past spring, the philosopher Richard J. Bernstein taught his final two classes at the New School for Social Research, in New York, where he had been a professor since 1989. One was a course on American pragmatism, the tradition to which his own work belongs. The other was a seminar on  I

I I’m not Michel Foucault, but here’s a history of sexuality, greatly abridged: First came the slut shamers. The traditionalist, patriarchal religious haranguers. Things weren’t great for men in the before times, but they were particularly unpleasant for women. Then came the sexual revolution of the 1960s and ’70s, which involved chucking all the rules. This had some good effects (ambitious women at last permitted to leave their houses and become doctors, lawyers, bosses) and some less good ones (moviemakers permitted to assault underage girls). In the 1990s and early 2000s, following however many backlashes against backlashes, the sexual revolution re-emerged as sex positivity.

I’m not Michel Foucault, but here’s a history of sexuality, greatly abridged: First came the slut shamers. The traditionalist, patriarchal religious haranguers. Things weren’t great for men in the before times, but they were particularly unpleasant for women. Then came the sexual revolution of the 1960s and ’70s, which involved chucking all the rules. This had some good effects (ambitious women at last permitted to leave their houses and become doctors, lawyers, bosses) and some less good ones (moviemakers permitted to assault underage girls). In the 1990s and early 2000s, following however many backlashes against backlashes, the sexual revolution re-emerged as sex positivity. SOMETIME THIS COMING

SOMETIME THIS COMING One name you don’t hear a lot these days is Thomas Piketty. In 2013, the French economist burst into the popular consciousness with the publication of

One name you don’t hear a lot these days is Thomas Piketty. In 2013, the French economist burst into the popular consciousness with the publication of

The invisibility of the disaster presents a serious difficulty to the filmmakers, who need their viewers to perceive it as the expert does. Their ingenious solution is found in the technical disaster movie’s pronounced ambience: the bustled score and sweaty palettes of Contagion; Chernobyl’s ghostly clanks and drones; the blare of Bloomberg terminals and pristine skylines of Margin Call. Through these effects, viewers are invited to pretend we know things we manifestly do not. We work through the night with Sullivan as he discovers his financial firm’s impending demise, study his stubbled face as he looks up from his illegible scrawl of equations before a pulsing monotone—and we simply know he’s uncovered something. The camera of Contagion fixates upon “fomites” (common objects that facilitate disease transmission), such that we learn to almost see viruses slithering over bus handles, glassware and casino chips. Chernobyl represents the presence of radiation with the throaty static of dosimeters (audible radiological instruments) that is often so loud and unnerving we forget we don’t exactly know what the sound means. Technical knowledge becomes an artificial sensorium, a collage of abstractions forced onto the nerve endings, always attempting to compensate for its baselessness.

The invisibility of the disaster presents a serious difficulty to the filmmakers, who need their viewers to perceive it as the expert does. Their ingenious solution is found in the technical disaster movie’s pronounced ambience: the bustled score and sweaty palettes of Contagion; Chernobyl’s ghostly clanks and drones; the blare of Bloomberg terminals and pristine skylines of Margin Call. Through these effects, viewers are invited to pretend we know things we manifestly do not. We work through the night with Sullivan as he discovers his financial firm’s impending demise, study his stubbled face as he looks up from his illegible scrawl of equations before a pulsing monotone—and we simply know he’s uncovered something. The camera of Contagion fixates upon “fomites” (common objects that facilitate disease transmission), such that we learn to almost see viruses slithering over bus handles, glassware and casino chips. Chernobyl represents the presence of radiation with the throaty static of dosimeters (audible radiological instruments) that is often so loud and unnerving we forget we don’t exactly know what the sound means. Technical knowledge becomes an artificial sensorium, a collage of abstractions forced onto the nerve endings, always attempting to compensate for its baselessness. Awe can mean many things. It can be witnessing a total solar eclipse. Or seeing your child take her first steps. Or hearing Lizzo perform live. But, while many of us know it when we feel it, awe is not easy to define. “Awe is the feeling of being in the presence of something vast that transcends your understanding of the world,” said Dacher Keltner, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley.

Awe can mean many things. It can be witnessing a total solar eclipse. Or seeing your child take her first steps. Or hearing Lizzo perform live. But, while many of us know it when we feel it, awe is not easy to define. “Awe is the feeling of being in the presence of something vast that transcends your understanding of the world,” said Dacher Keltner, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley. To learn to socialize, zebrafish need to trust their gut. Gut microbes encourage specialized cells to prune back extra connections in brain circuits that control social behavior, new University of Oregon research in zebrafish shows. The pruning is essential for the development of normal social behavior.

To learn to socialize, zebrafish need to trust their gut. Gut microbes encourage specialized cells to prune back extra connections in brain circuits that control social behavior, new University of Oregon research in zebrafish shows. The pruning is essential for the development of normal social behavior. Each of us constructs and lives a “narrative”,’ wrote the British neurologist Oliver Sacks, ‘this narrative is us’. Likewise the American cognitive psychologist Jerome Bruner: ‘Self is a perpetually rewritten story.’ And: ‘In the end, we become the autobiographical narratives by which we “tell about” our lives.’ Or a fellow American psychologist, Dan P McAdams: ‘We are all storytellers, and we are the stories we tell.’ And here’s the American moral philosopher J David Velleman: ‘We invent ourselves… but we really are the characters we invent.’ And, for good measure, another American philosopher, Daniel Dennett: ‘we are all virtuoso novelists, who find ourselves engaged in all sorts of behaviour… and we always put the best “faces” on it we can. We try to make all of our material cohere into a single good story. And that story is our autobiography. The chief fictional character at the centre of that autobiography is one’s self.’

Each of us constructs and lives a “narrative”,’ wrote the British neurologist Oliver Sacks, ‘this narrative is us’. Likewise the American cognitive psychologist Jerome Bruner: ‘Self is a perpetually rewritten story.’ And: ‘In the end, we become the autobiographical narratives by which we “tell about” our lives.’ Or a fellow American psychologist, Dan P McAdams: ‘We are all storytellers, and we are the stories we tell.’ And here’s the American moral philosopher J David Velleman: ‘We invent ourselves… but we really are the characters we invent.’ And, for good measure, another American philosopher, Daniel Dennett: ‘we are all virtuoso novelists, who find ourselves engaged in all sorts of behaviour… and we always put the best “faces” on it we can. We try to make all of our material cohere into a single good story. And that story is our autobiography. The chief fictional character at the centre of that autobiography is one’s self.’ What do Noam Chomsky, living legend of linguistics, Kai-Fu Lee, perhaps the most famous AI researcher in all of China, and Yejin Choi, the 2022 MacArthur Fellowship winner who was profiled earlier this week in The New York Times Magazine—and more than a dozen other scientists, economists, researchers, and elected officials—all have in common?

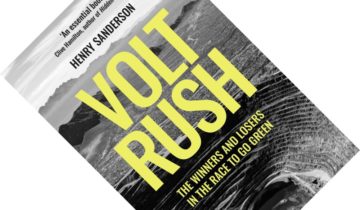

What do Noam Chomsky, living legend of linguistics, Kai-Fu Lee, perhaps the most famous AI researcher in all of China, and Yejin Choi, the 2022 MacArthur Fellowship winner who was profiled earlier this week in The New York Times Magazine—and more than a dozen other scientists, economists, researchers, and elected officials—all have in common? The problems created by humanity’s dependence on fossil fuels are widely appreciated, and governments and businesses are now pursuing renewable energy and electric vehicles as the solution. Less appreciated is that this new infrastructure will require the mining of vast amounts of metals, creating different problems. In Volt Rush, Financial Times journalist Henry Sanderson gives a well-rounded and thought-provoking exposé of the companies and characters behind the supply chain of foremost the batteries that will power the vehicles of the future. If you think a greener and cleaner world awaits us, Volt Rush makes it clear that this is far from a given.

The problems created by humanity’s dependence on fossil fuels are widely appreciated, and governments and businesses are now pursuing renewable energy and electric vehicles as the solution. Less appreciated is that this new infrastructure will require the mining of vast amounts of metals, creating different problems. In Volt Rush, Financial Times journalist Henry Sanderson gives a well-rounded and thought-provoking exposé of the companies and characters behind the supply chain of foremost the batteries that will power the vehicles of the future. If you think a greener and cleaner world awaits us, Volt Rush makes it clear that this is far from a given. I really enjoy doing it: it makes me feel good about myself. It gives me a boost, mentally and physically.” If these were your reactions to an activity, you’d surely be inclined to do it as often as you could. After all, aren’t a lot of us looking for ways to find more meaning in life and to be happier and healthier? What, then, is the act that elicits such positive responses? The answer: being

I really enjoy doing it: it makes me feel good about myself. It gives me a boost, mentally and physically.” If these were your reactions to an activity, you’d surely be inclined to do it as often as you could. After all, aren’t a lot of us looking for ways to find more meaning in life and to be happier and healthier? What, then, is the act that elicits such positive responses? The answer: being