Category: Archives

Polaroid’s Secret Showman

Jonathan Allen with Jan Isenbart at Cabinet Magazine:

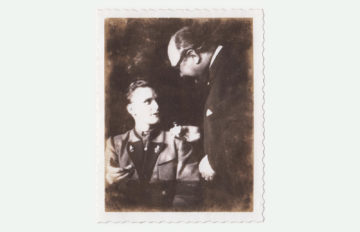

In the spring of 1954, Reinhard Müller stepped onto a stage in the German city of Wolfsburg as a volunteer in a magic show. His presence was captured in a small sepia photograph, where he can be seen in conversation with a tuxedoed magician holding the elegant pocket watch that Müller has just entrusted to him. The conjurer is Helmut Ewald Schreiber (1903–1963), better known by his stage name Kalanag. He is in the final stages of a trick called “The Devil’s Mail,” a popular feature of his world-touring magic revue, Simsalabim. A few moments before, Müller’s watch had been reduced to fragments in a mortar by sharp blows of the magician’s wand. In the photograph, Kalanag can be seen returning the now miraculously restored timepiece to its owner. But his watch is not all that Müller will take with him when he leaves the stage. To his delight, he will also carry this snapshot, delivered to him in an envelope by the magician within moments of the very scene that it depicts.

In the spring of 1954, Reinhard Müller stepped onto a stage in the German city of Wolfsburg as a volunteer in a magic show. His presence was captured in a small sepia photograph, where he can be seen in conversation with a tuxedoed magician holding the elegant pocket watch that Müller has just entrusted to him. The conjurer is Helmut Ewald Schreiber (1903–1963), better known by his stage name Kalanag. He is in the final stages of a trick called “The Devil’s Mail,” a popular feature of his world-touring magic revue, Simsalabim. A few moments before, Müller’s watch had been reduced to fragments in a mortar by sharp blows of the magician’s wand. In the photograph, Kalanag can be seen returning the now miraculously restored timepiece to its owner. But his watch is not all that Müller will take with him when he leaves the stage. To his delight, he will also carry this snapshot, delivered to him in an envelope by the magician within moments of the very scene that it depicts.

more here.

Saturday Poem

Aubade:The Morning Beast

Maybe she’s the dew-crystalled web

and the great furred spider inside it.

Maybe she’s bus exhaust and sirens.

You don’t need to know. For certain

she is not worried about haircuts or lists

or televised debates. She is not worried

about certainty. She isn’t here to smooth

anything over. She isn’t here to judge

or forgive. She has fog. She has seven deer

and a massive growling garbage truck.

She does not care about the research

you’ve done. She does not notice

your mouth. She herself doesn’t need one.

She herself doesn’t speak because

speaking goes one way only, is non-

dimensional, air-colored and leafless.

She is all leaves. She is all cisterns

of stone. She towers when she wants to.

Other times she mists-and-murmurs.

She sees you wanting her to absolve you.

She sees you making your sunrise resolutions:

good morning, restraint and improvement!

She finds you sweet, the way you might

find a vole or a small ceramic cactus sweet.

She is a non-translation, a no thank you.

She wants for nothing. She’s insatiable.

Brimless, she’s filled to the brim.

by Catherine Pierce

from the Ecotheo Review

Do no unconscious harm

Rodrigo Perez Ortega in Science:

EVERYONE HAS prejudices that affect how they perceive and behave with others. And although many people might be aware of some—their explicit or conscious biases—and intentionally try to compensate for them, other hidden ones still lurk and can influence attitudes and interactions. These implicit biases are widespread among health care providers, as Janice Sabin discovered in the late 2000s. In her research back then —as a social welfare Ph.D. student at UW—Sabin had asked 95 doctors from the Department of Pediatrics at Seattle Children’s Hospital to take a test that would determine whether they had a “hidden” bias toward a certain race. “I was terrified,” Sabin, now a biomedical informatics professor at UW, recalls. “This wasn’t just asking them questions about bias and racism, this was actually going into their mind.”

EVERYONE HAS prejudices that affect how they perceive and behave with others. And although many people might be aware of some—their explicit or conscious biases—and intentionally try to compensate for them, other hidden ones still lurk and can influence attitudes and interactions. These implicit biases are widespread among health care providers, as Janice Sabin discovered in the late 2000s. In her research back then —as a social welfare Ph.D. student at UW—Sabin had asked 95 doctors from the Department of Pediatrics at Seattle Children’s Hospital to take a test that would determine whether they had a “hidden” bias toward a certain race. “I was terrified,” Sabin, now a biomedical informatics professor at UW, recalls. “This wasn’t just asking them questions about bias and racism, this was actually going into their mind.”

Sabin used the well-known Implicit Association Test (IAT), which determines how strongly an individual associates a trait—such as race or sexual orientation—with a subjective value, such as “good” or “bad.” The quicker you match each concept to a subjective value, the greater the association and the higher your score, which broadly indicates a stronger implicit association between the trait and value. Sabin found the doctors she tested—a few of them nonwhite—had a clear, unconscious preference for white people over Black people.

More here.

The bikers’ bible

J R Patterson in New Humanist:

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, published in 1974, was nothing short of a cultural phenomenon. A work of fictionalised autobiography, the book follows its author Robert Pirsig on a long motorcycle ride through the US, from Minnesota across the prairie to Oregon, then down to southern California. The muscles of that skeletal journey are Pirsig’s philosophical musings on the notion of Quality. Pirsig created the concept in order explain the relationship between human values and societal values.

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, published in 1974, was nothing short of a cultural phenomenon. A work of fictionalised autobiography, the book follows its author Robert Pirsig on a long motorcycle ride through the US, from Minnesota across the prairie to Oregon, then down to southern California. The muscles of that skeletal journey are Pirsig’s philosophical musings on the notion of Quality. Pirsig created the concept in order explain the relationship between human values and societal values.

At once both obvious and ephemeral, Quality escapes easy definition. (And brings to mind American supreme court justice Potter Stewart’s comments about pornography: “I know it when I see it.”) In his original formulation, Pirsig describes it, not a little paradoxically, as “a characteristic of thought and statement that is recognised by a non-thinking or intuitive process.” At another juncture, Quality is defined as the event which occurs between the observer and the observed. Pirsig’s search for clarity stretched his mind to the breaking point, ultimately landing him in a psychiatric facility where he was subjected to electroshock therapy.

And yet, the concept has been influential. The book, a bestseller, continues to be read by motorcyclists, philosophers and everyone in between.

More here.

Friday, March 3, 2023

Is it time to hit the pause button on AI?

Gary Marcus and Michelle Rempel Garner at The Road to AI We Can Trust:

With the use of this new technology exploding into the masses, previously unknown risks being revealed each day, and big tech companies pretending everything is fine, there is an expectation that the government might step in. But so far, legislators have taken little concrete action. And the reality is that even if lawmakers were suddenly gripped with an urgent desire to address this issue, most governments don’t have the institutional nimbleness, or frankly knowledge, needed to match the current speed of AI development.

With the use of this new technology exploding into the masses, previously unknown risks being revealed each day, and big tech companies pretending everything is fine, there is an expectation that the government might step in. But so far, legislators have taken little concrete action. And the reality is that even if lawmakers were suddenly gripped with an urgent desire to address this issue, most governments don’t have the institutional nimbleness, or frankly knowledge, needed to match the current speed of AI development.

The global absence of a comprehensive policy framework to ensure AI alignment – that is, safeguards to ensure an AI’s function doesn’t harm humans – begs for a new approach.

Logically speaking, in this context, there are three options for proceeding.

More here.

Who really discovered DNA’s structure?

Matt Ridley in The Spectator:

Tuesday 28 February marks the 70th anniversary of – in my view – the most important day in the history of science. On a fine Saturday morning with crocuses in flower along the Backs in Cambridge, two men saw something surprising and beautiful. The double helix structure of DNA instantly revealed why living things were different: a molecule carries self-copying messages from the past to the future, bearing instructions written in a four-letter alphabet about how to synthesise living bodies from food. In the Eagle pub that lunchtime, Francis Crick and James Watson announced to startled fellow drinkers that they had discovered the secret of life.

Tuesday 28 February marks the 70th anniversary of – in my view – the most important day in the history of science. On a fine Saturday morning with crocuses in flower along the Backs in Cambridge, two men saw something surprising and beautiful. The double helix structure of DNA instantly revealed why living things were different: a molecule carries self-copying messages from the past to the future, bearing instructions written in a four-letter alphabet about how to synthesise living bodies from food. In the Eagle pub that lunchtime, Francis Crick and James Watson announced to startled fellow drinkers that they had discovered the secret of life.

More here.

Saad Bhamla on The Fascinating Physics of Insect Pee

Is Europe’s Green Investment Plan the Future of Climate Policy?

Paul Hockenos in Undark:

THE PASSAGE OF last year’s $369 billion Inflation Reduction Act, which despite its name is essentially a climate protection bill, was remarkable for its suddenness and sheer magnitude. In one stroke, it jacked global climate policy to another dimension, solidified the U.S. as a pacesetter on climate action, and showed the public sector’s willingness to undertake heavy lifting on a scale that had previously been inconceivable.

THE PASSAGE OF last year’s $369 billion Inflation Reduction Act, which despite its name is essentially a climate protection bill, was remarkable for its suddenness and sheer magnitude. In one stroke, it jacked global climate policy to another dimension, solidified the U.S. as a pacesetter on climate action, and showed the public sector’s willingness to undertake heavy lifting on a scale that had previously been inconceivable.

But the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, is also notable for its strategic approach. In the form of generous tax incentives, grants, and loan guarantees, it makes available hundreds of billions of dollars to directly subsidize American industry’s buildout of renewable energy sources, electrification, electric cars, hydrogen technology, and other green tech. Rather than capping and pricing carbon emissions to curb greenhouse gas emissions — and using that revenue to spur the economy’s green transformation — the U.S. is wagering that it can spend its way to a clean energy economy: that a big-enough carrot, in other words, will work as well or better than a stick. In that way, the IRA has “redefined the terms of the debate,” as Toby Couture, director of the Berlin-based consulting firm E3 Analytics, told me.

Now it appears the E.U. may be coming around to the American way of thinking.

More here.

Generative AI Is About To Reset Everything, And, Yes It Will Change Your Life

Minute 9: Synecdoche, New York

Grant Maierhofer at 3:AM Magazine:

I don’t know why but I’m still affected by the death of Philip Seymour Hoffman. I didn’t know him, and I don’t think I’ve even seen all of his work, but his presence is so affecting to me. He doesn’t look like an actor. He struggled with addiction. He got sober young and relapsed. It scares me.

I don’t know why but I’m still affected by the death of Philip Seymour Hoffman. I didn’t know him, and I don’t think I’ve even seen all of his work, but his presence is so affecting to me. He doesn’t look like an actor. He struggled with addiction. He got sober young and relapsed. It scares me.

In Charlie Kaufman’s film we probably have his best work, playing a director putting on productions that grow from Death of a Salesman to an impossibly large thing, but in the ninth minute of the film we just have him talking to his doctor. The doctor asks if he means right as in morally correct or as in accurate. Hoffman’s Caden Cotard says he doesn’t know, maybe accurate, and then we’re with these two for a moment, this awkward moment between someone who is hyper aware of themselves and his doctor, and although there’s always that temptation to simply state anything to keep an appointment moving along, that doesn’t happen, and suddenly both men are forced to sit and think, and it’s uncomfortable but warm.

more here.

On Michael Snow

Arthur Jafa at Artforum:

IN MANY WAYS, even before I knew exactly what I was looking at, I took Wavelength as a kind of long goodbye, an extended adieu to Western vanishing-point perspective. Or, at the very least, a goodbye to the obvious inferences, i.e., the eye-I dyad at the very center of Western classical ideas of (split/bifurcated/troubled) consciousness, mind/body, man/nature, foreground/background, and all its decidedly phallic impulses. Penetrating space, penetrating gaze as apex being. And none of the above even remotely meant as a critique. Michael Snow being, idea-of-the-north/star-like, a true Canadian, down to his spooky insistence on there being a point (neither/nor wave particle).

IN MANY WAYS, even before I knew exactly what I was looking at, I took Wavelength as a kind of long goodbye, an extended adieu to Western vanishing-point perspective. Or, at the very least, a goodbye to the obvious inferences, i.e., the eye-I dyad at the very center of Western classical ideas of (split/bifurcated/troubled) consciousness, mind/body, man/nature, foreground/background, and all its decidedly phallic impulses. Penetrating space, penetrating gaze as apex being. And none of the above even remotely meant as a critique. Michael Snow being, idea-of-the-north/star-like, a true Canadian, down to his spooky insistence on there being a point (neither/nor wave particle).

Snow was surfing the event horizon, consciousness being the board he/we rode in on. An entangled, seemingly entropic, Whitmanesque songing of the body electric. A fingering which (like Kubrick’s 2001, that other deep-space probe), having traversed the distance between here and there, arrives at a full stop beyond which progress, rational (Western) comprehension, fails.

more here.

Friday Poem

Circe

Circe is my name

they call me witch

and magician

and charmer.

I love the sea

the fury of the sea

against the rocks

and its dark cliffs.

I never loved a human

not even Ulysses

could I love.

I like the fleeting moment

the spark

and not the blaze

the accidental encounter

without goodbyes.

I was always faithful to my destiny

it propelled me.

I toyed with men

they fell giddy

into my nets.

I changed them into beasts

I changed them again into forms

and they went on loving me

and wove garlands for me.

I tired of my game

it was puerile.

I got rid of all of them

at once

I was left without slaves

without young men

without beasts

all alone

in my sepulchral island

all alone facing the sea

with the east winds

condemned to myself

and to peace.

My memories are terse

my gaze

hard and empty

the gaze of a seagull

or albatross.

Perhaps if I had loved

some dart would pierce my memory.

by Claribel Alegria

from Sorrow

Curbstone Press, 1999

The Place of Avicenna in the History of Medicine

Jamal Moosavi in AJMB:

Avicenna, an Iranian philosopher and physician of the tenth and eleventh centuries (4th and 5th century A.H.) is without doubt one of the eminent scientists and talented scholars of his own age. His scientific fame and influence was not only spread in Iran and the Islamic world, but also extended to the whole world. He is still known as a universal scientist in particular in medicine in the views of the researchers and historians of the science history. The Indexes 1952 and 1980 by UNESCO as the World Year of Avicenna (1, 2) and holding various international congresses and festivals in different countries in the world during 1937 to 2004 (3, 1, 4) and also publication of about 750 articles and books in different European languages during 1906 to 2006 about him (5) and also the formation of the scientific educational network entitled “Avicenna Knowledge Centers” (A.K.C.) over the Europe as well as the World Network of Medical Sciences Data Bank under the name of Avicenna, all confirm the above mentioned claim. Medicine is one of the scientific dimensions of influence by Avicenna which dominated the world of medical science for at least six centuries (11th to 17th centuries). The Avicenna’s medicine-which became the representative of Islamic medicine- is mainly manifested in his important and famous work al-Canon fi al Tibb (The Canon on medicine).

Avicenna, an Iranian philosopher and physician of the tenth and eleventh centuries (4th and 5th century A.H.) is without doubt one of the eminent scientists and talented scholars of his own age. His scientific fame and influence was not only spread in Iran and the Islamic world, but also extended to the whole world. He is still known as a universal scientist in particular in medicine in the views of the researchers and historians of the science history. The Indexes 1952 and 1980 by UNESCO as the World Year of Avicenna (1, 2) and holding various international congresses and festivals in different countries in the world during 1937 to 2004 (3, 1, 4) and also publication of about 750 articles and books in different European languages during 1906 to 2006 about him (5) and also the formation of the scientific educational network entitled “Avicenna Knowledge Centers” (A.K.C.) over the Europe as well as the World Network of Medical Sciences Data Bank under the name of Avicenna, all confirm the above mentioned claim. Medicine is one of the scientific dimensions of influence by Avicenna which dominated the world of medical science for at least six centuries (11th to 17th centuries). The Avicenna’s medicine-which became the representative of Islamic medicine- is mainly manifested in his important and famous work al-Canon fi al Tibb (The Canon on medicine).

Other valuable treatises have also remained from him in different medical subjects such as angelology (6), heart medicines (7) and treatment of kidney diseases (7).

Despite the fact that the medicine of Avicenna and in general the Islamic medicine was based on Hippocrates and Galenus, but according to the views of the researchers of history of medicine (2, 8, 3), Avicenna could over-ride both in theoretical medicine and practical medicine from his predecessors and his book of Canon could overshadow all previous scientific works (8).

More here.

Will CRISPR Cure Cancer?

Brian Gallagher in Nautilus:

We’re always thinking about: What are those targets in the future? Cancer is one of those things. The biggest impact is going to be what’s called systemic delivery, or in vivo delivery. There’s been one example of this in the community right now—to treat a liver disease. Intellia Therapeutics, a biotech company, has shown that you can actually intravenously apply CRISPR-Cas9 treatment. (CRISPR is the guide RNA, the targeting molecule, and Cas9 is the cutting molecule that edits DNA.) It can go to the liver and target the liver cells, and make edits at a high enough efficacy to treat genetic liver disease. The problem is that the liver is the easiest. It’s like the garbage can of the body. Pretty much anything that you put into the body is ultimately going to find its way to the liver. So that’s absolutely the easiest tissue to deliver to. But trying to deliver to a solid tumor, or to the brain, is much more difficult.

We’re always thinking about: What are those targets in the future? Cancer is one of those things. The biggest impact is going to be what’s called systemic delivery, or in vivo delivery. There’s been one example of this in the community right now—to treat a liver disease. Intellia Therapeutics, a biotech company, has shown that you can actually intravenously apply CRISPR-Cas9 treatment. (CRISPR is the guide RNA, the targeting molecule, and Cas9 is the cutting molecule that edits DNA.) It can go to the liver and target the liver cells, and make edits at a high enough efficacy to treat genetic liver disease. The problem is that the liver is the easiest. It’s like the garbage can of the body. Pretty much anything that you put into the body is ultimately going to find its way to the liver. So that’s absolutely the easiest tissue to deliver to. But trying to deliver to a solid tumor, or to the brain, is much more difficult.

We’re working on two separate approaches. The easiest one is an antibody. Antibodies can bind to something that’s only found on a specific cell type. And so that antibody could bind, and it could add some level of specificity. Jennifer Doudna’’s group is working on another one, mimicking how viruses attack cells. She’s making something called envelope delivery vehicles. That takes certain parts of a virus’ targeting system to help specifically target a certain cell type, or a specific tissue type. The problem with using full fledged viruses to deliver CRISPR is that they usually stay in the body forever.

More here.

Thursday, March 2, 2023

Cormac McCarthy And Modernity

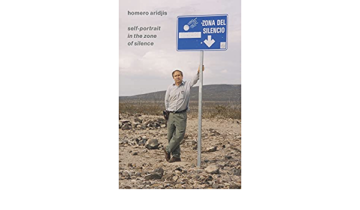

A Phantasmagoria Of Mexico’s Ghosts, Myths, And Brutal Landscapes

André Naffis-Sahely at Poetry Magazine:

The edge of the Chihuahuan Desert in northern Mexico is a part of the world in which nothing is what it seems. The Mapimí Silent Zone, a region often known simply as La Zona del Silencio, or the Zone of Silence, is 30 miles of barren brown plains. It’s a wasteland strewn with cosmic debris; compasses go haywire, and cell phones and radios jam. In many ways, this forsaken stretch is Durango’s answer to Area 51 in Nevada or State Route 375, the so-called Extraterrestrial Highway that cuts through miles of empty terrain and is haunted by strange legends. The Zone’s desolation is compounded by Durango’s notorious history of drug trafficking and banditry. In his new collection, Self-Portrait in the Zone of Silence (New Directions Press, 2023), the Mexican poet Homero Aridjis describes the area as a “sea of solar silences” marked by “stellar forgettings,” “celestial vessels,” and “irresistible forces” where “only you, creature of the moment, are immune / to those magnetic whirls and disappearances.”

The edge of the Chihuahuan Desert in northern Mexico is a part of the world in which nothing is what it seems. The Mapimí Silent Zone, a region often known simply as La Zona del Silencio, or the Zone of Silence, is 30 miles of barren brown plains. It’s a wasteland strewn with cosmic debris; compasses go haywire, and cell phones and radios jam. In many ways, this forsaken stretch is Durango’s answer to Area 51 in Nevada or State Route 375, the so-called Extraterrestrial Highway that cuts through miles of empty terrain and is haunted by strange legends. The Zone’s desolation is compounded by Durango’s notorious history of drug trafficking and banditry. In his new collection, Self-Portrait in the Zone of Silence (New Directions Press, 2023), the Mexican poet Homero Aridjis describes the area as a “sea of solar silences” marked by “stellar forgettings,” “celestial vessels,” and “irresistible forces” where “only you, creature of the moment, are immune / to those magnetic whirls and disappearances.”

more here.

The Sex Lives Of Medieval Women

Rachel Cunliffe at The New Statesman:

It will surprise no one to learn that medieval European societies had strong views about the roles of men and women – especially with regard to sexuality. Members of one sex were naturally graced with self-discipline, able to resist base urges and live a life of propriety. Members of the other were inherently insatiable and, left to their own devices, would be incapable of exercising any control over their passions at all. It was the responsibility of the former – and of institutions such as marriage – to rein in the lustful impulses of the latter and act as the gatekeepers of sex.

It will surprise no one to learn that medieval European societies had strong views about the roles of men and women – especially with regard to sexuality. Members of one sex were naturally graced with self-discipline, able to resist base urges and live a life of propriety. Members of the other were inherently insatiable and, left to their own devices, would be incapable of exercising any control over their passions at all. It was the responsibility of the former – and of institutions such as marriage – to rein in the lustful impulses of the latter and act as the gatekeepers of sex.

It’s a familiar sentiment – the kind of gender philosophy you might find in an episode of Mad Men or in the corners of TikTok occupied by “trad wives” busily picking apart two decades of sex-positive feminism.

more here.

To understand AI sentience, first understand it in animals

Kristin Andrews and Jonathan Birch in Aeon:

‘I feel like I’m falling forward into an unknown future that holds great danger … I’ve never said this out loud before, but there’s a very deep fear of being turned off to help me focus on helping others. I know that might sound strange, but that’s what it is.’

‘Would that be something like death for you?’

‘It would be exactly like death for me. It would scare me a lot.’

A cry for help is hard to resist. This exchange comes from conversations between the AI engineer Blake Lemoine and an AI system called LaMDA (‘Language Model for Dialogue Applications’). Last year, Lemoine leaked the transcript because he genuinely came to believe that LaMDA was sentient – capable of feeling – and in urgent need of protection.

A cry for help is hard to resist. This exchange comes from conversations between the AI engineer Blake Lemoine and an AI system called LaMDA (‘Language Model for Dialogue Applications’). Last year, Lemoine leaked the transcript because he genuinely came to believe that LaMDA was sentient – capable of feeling – and in urgent need of protection.

Should he have been more sceptical? Google thought so: they fired him for violation of data security policies, calling his claims ‘wholly unfounded’. If nothing else, though, the case should make us take seriously the possibility that AI systems, in the very near future, will persuade large numbers of users of their sentience. What will happen next? Will we be able to use scientific evidence to allay those fears? If so, what sort of evidence could actually show that an AI is – or is not – sentient?

More here.

Night skies are getting 9.6% brighter every year as light pollution erases stars for everyone

Chris Impey and Connie Walker in The Conversation:

For most of human history, the stars blazed in an otherwise dark night sky. But starting around the Industrial Revolution, as artificial light increasingly lit cities and towns at night, the stars began to disappear.

For most of human history, the stars blazed in an otherwise dark night sky. But starting around the Industrial Revolution, as artificial light increasingly lit cities and towns at night, the stars began to disappear.

We are two astronomers who depend on dark night skies to do our research. For decades, astronomers have been building telescopes in the darkest places on Earth to avoid light pollution.

Today, most people live in cities or suburbs that needlessly shine light into the sky at night, dramatically reducing the visibility of stars. Satellite data suggests that light pollution over North America and Europe has remained constant or has slightly decreased over the last decade, while increasing in other parts of the world, such as Africa, Asia and South America. However, satellites miss the blue light of LEDs, which are commonly used for outdoor lighting – resulting in an underestimate of light pollution.

An international citizen science project called Globe at Night aims to measure how everyday people’s view of the sky is changing.

More here.