Dan Musgrave at Longreads:

I had been volunteering at the ape house for four months before I was invited to meet Nathan. It was December and I’d just spent my first Christmas with the apes. Everyone but the director and I had left for the day. The night sky spilled over the glass-ceilinged, central atrium we called the greenhouse. Despite the snow outside, the greenhouse air was warm and ample. Moving toward the padlocked cage door, I felt light, as if I was about to float up into that dotted black expanse above me, rather than enter a room I’d cleaned feces and orange peels out of hours earlier.

I had been volunteering at the ape house for four months before I was invited to meet Nathan. It was December and I’d just spent my first Christmas with the apes. Everyone but the director and I had left for the day. The night sky spilled over the glass-ceilinged, central atrium we called the greenhouse. Despite the snow outside, the greenhouse air was warm and ample. Moving toward the padlocked cage door, I felt light, as if I was about to float up into that dotted black expanse above me, rather than enter a room I’d cleaned feces and orange peels out of hours earlier.

I juggled my keys and the offering I’d brought with me — a tub of yogurt, a couple of bananas, Gatorade, and some blankets. With the two padlocks removed, I entered, sat, and arranged the gifts in an arc around me. Even though I was planted firmly on the glazed concrete floor, I swayed.

In the adjacent room, watching everything I did through the glass portion of a mechanical sliding door, was Nathan. Five years old to my 21. He was stout, wide-shouldered, with thick muscled arms, but almost twiggy legs. Nathan was, simply put, a cool little dude.

More here.

The common definition of free will often has problems when relating to desire and power to choose. An alternative definition that ties free will to different outcomes for life despite one’s past is supported by the probabilistic nature of quantum physics. This definition is compatible with the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum physics, which refutes the conclusion that randomness does not imply free will.

The common definition of free will often has problems when relating to desire and power to choose. An alternative definition that ties free will to different outcomes for life despite one’s past is supported by the probabilistic nature of quantum physics. This definition is compatible with the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum physics, which refutes the conclusion that randomness does not imply free will.

There was hysteria in the air at 81st Street Theatre in New York. Deep within the building, behind its white neoclassical arches and away from the steady chatter of crowds of adoring fans outside, a new kind of celebrity singer was walking onto a black-and-silver stage. It was February 1929, and just a few months earlier, Rudy Vallée had been an obscure graduate best known to the listeners of WABC radio in New York. He wasn’t considered particularly good looking: one biting critic later called him

There was hysteria in the air at 81st Street Theatre in New York. Deep within the building, behind its white neoclassical arches and away from the steady chatter of crowds of adoring fans outside, a new kind of celebrity singer was walking onto a black-and-silver stage. It was February 1929, and just a few months earlier, Rudy Vallée had been an obscure graduate best known to the listeners of WABC radio in New York. He wasn’t considered particularly good looking: one biting critic later called him  Given all the attention to President Biden’s cognitive fitness for a second presidential term, it seems fair, even mandatory, to assess Donald Trump’s performance at a televised town hall in Manchester, N.H., on Wednesday night through the same lens: How clear was his thinking? How sturdy his tether to reality? How appropriate his demeanor?

Given all the attention to President Biden’s cognitive fitness for a second presidential term, it seems fair, even mandatory, to assess Donald Trump’s performance at a televised town hall in Manchester, N.H., on Wednesday night through the same lens: How clear was his thinking? How sturdy his tether to reality? How appropriate his demeanor? The coincidence of artistic and academic talent is not uncommon in brilliant people; how to reconcile and channel those talents is often a challenge. The world is getting better acquainted with such a talent, 1950s singer-songwriter Elizabeth Converse, with the release of

The coincidence of artistic and academic talent is not uncommon in brilliant people; how to reconcile and channel those talents is often a challenge. The world is getting better acquainted with such a talent, 1950s singer-songwriter Elizabeth Converse, with the release of  When King was assassinated, in 1968, he was generally viewed as a leader with a mixed record.

When King was assassinated, in 1968, he was generally viewed as a leader with a mixed record.  T.C. Boyle lives in Santa Barbara, an area in California that has been steadily ravaged by extreme weather in recent years. His 2011 novel

T.C. Boyle lives in Santa Barbara, an area in California that has been steadily ravaged by extreme weather in recent years. His 2011 novel  There have recently been lots of discussions about the risks of AI, whether in the short term with existing methods or in the longer term with advances we can anticipate. I have been very vocal about the importance of accelerating regulation, both nationally and internationally, which I think could help us mitigate issues of discrimination, bias, fake news, disinformation, etc. Other anticipated negative outcomes like shocks to job markets require changes in the social safety net and education system. The use of AI in the military, especially with lethal autonomous weapons has been a big concern for many years and clearly requires international coordination.

There have recently been lots of discussions about the risks of AI, whether in the short term with existing methods or in the longer term with advances we can anticipate. I have been very vocal about the importance of accelerating regulation, both nationally and internationally, which I think could help us mitigate issues of discrimination, bias, fake news, disinformation, etc. Other anticipated negative outcomes like shocks to job markets require changes in the social safety net and education system. The use of AI in the military, especially with lethal autonomous weapons has been a big concern for many years and clearly requires international coordination. The core moral thread that holds the modern criminal law doctrine together is that only morally culpable humans should be convicted of a stigmatic criminal offense. A pig cannot be a sensible target of blame. Neither can a child, nor a mentally ill person, nor an offender who lacked the necessary « guilty mind » (that is, she did not act with intention, recklessness or criminal negligence), nor an offender who acted in self-defense or in a state of necessity. The culpability principle that stands as the moral foundation of twentieth-century criminal law doctrine is a victory of rationality. The loser, here, is the human id that cannot let go — that asks: « Am I supposed to forgo blame because the conduct of the perpetrator of the crime did not match the legal test of recklessness? »

The core moral thread that holds the modern criminal law doctrine together is that only morally culpable humans should be convicted of a stigmatic criminal offense. A pig cannot be a sensible target of blame. Neither can a child, nor a mentally ill person, nor an offender who lacked the necessary « guilty mind » (that is, she did not act with intention, recklessness or criminal negligence), nor an offender who acted in self-defense or in a state of necessity. The culpability principle that stands as the moral foundation of twentieth-century criminal law doctrine is a victory of rationality. The loser, here, is the human id that cannot let go — that asks: « Am I supposed to forgo blame because the conduct of the perpetrator of the crime did not match the legal test of recklessness? » If all that is not enough, the critical theorists also have to reckon with the strange allure the Frankfurt School and French theory have in certain corners of the right. Michel Foucault, never a reliable ally of the left, was taken up anew by conservatives during the COVID pandemic, when the concept of biopower seemed eerily apt. Giorgio Agamben, an heir to Foucault’s account of biopower, has alienated large parts of the left and won new friends on the right through his power analysis of the global pandemic response. The critical theory journal Telos, along with some of its regular contributors, was never averse to thought from outside the left but is now seen in some quarters as positively right-wing. One of the intellectual godfathers of the latest incarnation of the New Right is Nick Land, who was once a leading figure in a cutting-edge school of digital media studies influenced by the French theory luminaries Georges Bataille and Jean Baudrillard.

If all that is not enough, the critical theorists also have to reckon with the strange allure the Frankfurt School and French theory have in certain corners of the right. Michel Foucault, never a reliable ally of the left, was taken up anew by conservatives during the COVID pandemic, when the concept of biopower seemed eerily apt. Giorgio Agamben, an heir to Foucault’s account of biopower, has alienated large parts of the left and won new friends on the right through his power analysis of the global pandemic response. The critical theory journal Telos, along with some of its regular contributors, was never averse to thought from outside the left but is now seen in some quarters as positively right-wing. One of the intellectual godfathers of the latest incarnation of the New Right is Nick Land, who was once a leading figure in a cutting-edge school of digital media studies influenced by the French theory luminaries Georges Bataille and Jean Baudrillard. In 1849 Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the 21-year-old poet-artist and founder member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, met a milliner’s assistant named Elizabeth Siddal. She was the daughter of a cutlery maker and had artistic aspirations. He was from a highly cultured Anglo-Italian family – his father was a Dante scholar, one of his mother’s brothers was John William Polidori, Lord Byron’s doctor and author of the first vampire story. By 1852 Siddal had become Rossetti’s pupil, lover and primary model and he was possessive enough to stop her sitting for other painters in the Pre-Raphaelite circle. There was a degree of transmutation in the relationship, too: at times Lizzie was more than flesh and blood, personifying his idea of perfect womanhood that justified a love that transgressed social station.

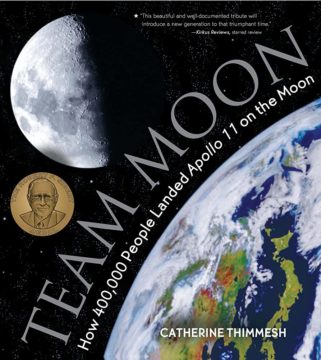

In 1849 Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the 21-year-old poet-artist and founder member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, met a milliner’s assistant named Elizabeth Siddal. She was the daughter of a cutlery maker and had artistic aspirations. He was from a highly cultured Anglo-Italian family – his father was a Dante scholar, one of his mother’s brothers was John William Polidori, Lord Byron’s doctor and author of the first vampire story. By 1852 Siddal had become Rossetti’s pupil, lover and primary model and he was possessive enough to stop her sitting for other painters in the Pre-Raphaelite circle. There was a degree of transmutation in the relationship, too: at times Lizzie was more than flesh and blood, personifying his idea of perfect womanhood that justified a love that transgressed social station. With alarms sounding and fuel running out, Neil Armstrong came within seconds of crashing the Apollo 11 landing module: “BAM! Suddenly, the master alarm in the lunar module rang out for attention with all the racket of a fire bell going off in a broom closet. ‘Program alarm,’ astronaut Neil Armstrong called out from the LM (‘LEM’) in a clipped but calm voice. ‘It’s a “twelve-oh-two.”‘ “‘1202,’ repeated astronaut Buzz Aldrin. They were 33,500 feet from the moon.

With alarms sounding and fuel running out, Neil Armstrong came within seconds of crashing the Apollo 11 landing module: “BAM! Suddenly, the master alarm in the lunar module rang out for attention with all the racket of a fire bell going off in a broom closet. ‘Program alarm,’ astronaut Neil Armstrong called out from the LM (‘LEM’) in a clipped but calm voice. ‘It’s a “twelve-oh-two.”‘ “‘1202,’ repeated astronaut Buzz Aldrin. They were 33,500 feet from the moon. Shortly after the birth of his sister Virginia in 1951, Springsteen’s family moved in with his paternal grandparents. They would stay there through 1956, but the years spent in that house would remain with Springsteen, a thing to untangle. It was a period of his childhood that, in his telling, would come to the fore in Nebraska.

Shortly after the birth of his sister Virginia in 1951, Springsteen’s family moved in with his paternal grandparents. They would stay there through 1956, but the years spent in that house would remain with Springsteen, a thing to untangle. It was a period of his childhood that, in his telling, would come to the fore in Nebraska.