Category: Archives

Sunday, May 14, 2023

An Interview with Eula Biss

Mara Naselli in The Believer:

In all her work, Biss scrutinizes the nature of our connection in American life. In one of her early essays, “Time and Distance Overcome,” she looks at how telephone poles, instruments of communication, became gallows in public lynchings across the country in the early twentieth century. Vaccines—our greatest collective defense against viral disease—become a symbol of violation and trespass. Money, our shared concrete metaphor of value, becomes a tool of exclusion. Each subject Biss examines exposes the contested ground on which we make and remake our American identities.

In all her work, Biss scrutinizes the nature of our connection in American life. In one of her early essays, “Time and Distance Overcome,” she looks at how telephone poles, instruments of communication, became gallows in public lynchings across the country in the early twentieth century. Vaccines—our greatest collective defense against viral disease—become a symbol of violation and trespass. Money, our shared concrete metaphor of value, becomes a tool of exclusion. Each subject Biss examines exposes the contested ground on which we make and remake our American identities.

More here.

Physicists Create Elusive Particles That Remember Their Pasts

Charlie Wood in Quanta:

Forty years ago, Frank Wilczek was mulling over a bizarre type of particle that could live only in a flat universe. Had he put pen to paper and done the calculations, Wilczek would have found that these then-theoretical particles held an otherworldly memory of their past, one woven too thoroughly into the fabric of reality for any one disturbance to erase it.

Forty years ago, Frank Wilczek was mulling over a bizarre type of particle that could live only in a flat universe. Had he put pen to paper and done the calculations, Wilczek would have found that these then-theoretical particles held an otherworldly memory of their past, one woven too thoroughly into the fabric of reality for any one disturbance to erase it.

However, seeing no reason that nature should allow such strange beasts to exist, the future Nobel prize-winning physicist chose not to follow his thought experiments to their most outlandish conclusions — despite the objections of his collaborator Anthony Zee, a renowned theoretical physicist at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

“I said, ‘Come on, Tony, people are going to make fun of us,’” said Wilczek, now a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Others weren’t so reluctant. Researchers have spent millions of dollars over the past three decades or so trying to capture and tame the particlelike objects, which go by the cryptic moniker of non-abelian anyons.

More here.

The cultural legacy of Bruno Schulz

David Stromberg in The Hedgehog Review:

Bruno Schulz is an author who never tires of being discovered. A writer and artist whose known corpus includes two slim collections of stories, a bundle of letters, and a handful of visual works, mostly drawings. Schulz was born in 1892 in Drohobycz, a small Galician town that was then under Austro-Hungarian rule. He died in that same town in 1942, shot in the head by a Nazi officer. His life and work would likely have been unknown but for the efforts of a handful of people for whom his work meant the world.

Bruno Schulz is an author who never tires of being discovered. A writer and artist whose known corpus includes two slim collections of stories, a bundle of letters, and a handful of visual works, mostly drawings. Schulz was born in 1892 in Drohobycz, a small Galician town that was then under Austro-Hungarian rule. He died in that same town in 1942, shot in the head by a Nazi officer. His life and work would likely have been unknown but for the efforts of a handful of people for whom his work meant the world.

Schulz was a master of the unrealized. He used language to give expression to the fancies of the mind. He wrote not about events but about the mental impressions of yearning, hoping, dreaming. He was rooted more firmly in the possible than the actualized. His words traveled on intellectual journeys of philosophical meandering. He brought his prose into the realm of the unfinished. This is part of what made him so attractive to readers in the post–World War II era. His imagination was an open field onto which others could project their own fanciful desire, nostalgia, and regret.

More here.

What is the future of AI? Google and the EU have very different ideas

Chris Stokel-Walker in New Scientist:

The race to roll out artificial intelligence is happening as quickly as the race to contain it – as two key moments this week demonstrate.

The race to roll out artificial intelligence is happening as quickly as the race to contain it – as two key moments this week demonstrate.

On 10 May, Google announced plans to deploy new large language models, which use machine learning techniques to generate text, across its existing products. “We are reimagining all of our core products, including search,” said Sundar Pichai, the CEO of Google’s parent company Alphabet, at a press conference. The move is widely seen as a response to Microsoft adding similar functionality to its search engine, Bing.

A day later, politicians in the European Union agreed on new rules dictating how and when AI can be used. The bloc’s AI Act has been years in the making, but has moved quickly to stay up to date: in the past month, legislators drafted and passed rules dictating the use of generative AIs, the popularity of which has exploded in the past six months.

More here.

Jealous Laughter

Joanna Biggs in Granta:

A friend of mine used to joke that women writers discovered friendship in 2015, when the last volume of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet came out. I laughed, but I knew what he meant. It is easy to think of men who navigated the literary world together: Jonson and Shakespeare, Wordsworth and Coleridge, Johnson and Boswell, Shelley and Byron, Marx and Engels, Sartre and Camus, Bellow and Roth, Hughes and Heaney, Amis and Barnes. In Weimar for a day in summer 2014, bitter laughter rose in me when I emerged into Theaterplatz to find a monument to literary bro-dom: Goethe and Schiller in bronze, each with a hand on a shared crown of laurels. With stout folds in Goethe’s breeches and pupils missing from Schiller’s eyes, the unlovely statue had been cast in 1857, twenty-five years after Goethe died, and had stood for more than a century facing the stage where Goethe had directed many of Schiller’s plays. In the early twentieth century, copies of the monument were made for San Francisco, Cleveland, Milwaukee and Syracuse and erected in parks in those cities. I laughed some more when I found that out. Is there such a thing as jealous laughter?

A friend of mine used to joke that women writers discovered friendship in 2015, when the last volume of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet came out. I laughed, but I knew what he meant. It is easy to think of men who navigated the literary world together: Jonson and Shakespeare, Wordsworth and Coleridge, Johnson and Boswell, Shelley and Byron, Marx and Engels, Sartre and Camus, Bellow and Roth, Hughes and Heaney, Amis and Barnes. In Weimar for a day in summer 2014, bitter laughter rose in me when I emerged into Theaterplatz to find a monument to literary bro-dom: Goethe and Schiller in bronze, each with a hand on a shared crown of laurels. With stout folds in Goethe’s breeches and pupils missing from Schiller’s eyes, the unlovely statue had been cast in 1857, twenty-five years after Goethe died, and had stood for more than a century facing the stage where Goethe had directed many of Schiller’s plays. In the early twentieth century, copies of the monument were made for San Francisco, Cleveland, Milwaukee and Syracuse and erected in parks in those cities. I laughed some more when I found that out. Is there such a thing as jealous laughter?

I was lonely back then. Sure, I was married to another writer, but he loved me, so he couldn’t not love my writing. Spouses are so implicated in each other’s success that support is de rigueur and unremarkable. And in any case men hadn’t forgone friendship when they’d been married to writers. Women writers had sisters, as Charlotte Brontё did in Emily and Anne, and rivals, as Virginia Woolf did in Katherine Mansfield. Or they were solitary because they were first, like Mary Wollstonecraft, or because they were modest, like Jane Austen. Woolf said that to write a woman needs a room of her own with a lock on the door and a sustaining income, but she also said that women need to be more confident, aware of their own traditions, willing to write in new forms – all things that are hard to do on one’s own, and nearly impossible to address for long without friends to advise, remind and encourage.

More here.

A Mother’s Day Message: Wise Words from Anna Quindlen

Excerpted from Anna Qunidlen’s book Loud and Clear:

If not for the photographs I might have a hard time believing they ever existed. The pensive infant with the swipe of dark bangs and the black button eyes of a Raggedy Andy doll. The placid baby with the yellow ringlets and the high piping voice. The sturdy toddler with the lower lip that curled into an apostrophe above her chin.

If not for the photographs I might have a hard time believing they ever existed. The pensive infant with the swipe of dark bangs and the black button eyes of a Raggedy Andy doll. The placid baby with the yellow ringlets and the high piping voice. The sturdy toddler with the lower lip that curled into an apostrophe above her chin.

All my babies are gone now. I say this not in sorrow but in disbelief. I take great satisfaction in what I have today: three almost adults, two taller than me, one closing in fast. Three people who read the same books I do and have learned not to be afraid of disagreeing with me in their opinion of them, who sometimes tell vulgar jokes that make me laugh until I choke and cry, who need razor blades and shower gel and privacy, who want to keep their doors closed more than I like. Who, miraculously, go to the bathroom, zip up their jackets, and move food from plate to mouth all by themselves. Like the trick soap I bought for the bathroom with a rubber ducky at its center, the baby is buried deep within each, barely discernible except through the unreliable haze of the past.

More here.

Sunday Poem

—Then and now tangled beyond belief.

…………………………. —Anonymous

The Golden Era

It was a time when babies cried

inside their mother’s wombs

because children always tell the truth.

Wealth was measured in cream for coffee

And chicken for soup.

The days of the rich

were made of imported chocolate

and hair spray.

The days of the poor

were of cold tea

and thin air.

It was the time when God

was taking orders in a restaurant

and delivered steak and fondue

to only one part of the town.

On the town streets,

the saints were walking without shoes.

It was a time when no one talked,

but everyone clapped

and sang.

We found out we were happy

from the news.

It was a time

when no one told us

what would happen,

but everyone knew.

by Claudia Serea

from The Red Wheelbarrow, #6, 2013

Menahem Pressler (1923 – 2023) Pianist

Stanley Deser (1931 – 2023) Physicist

Rita Lee (1947 – 2023) Singer And Composer

Saturday, May 13, 2023

Ian Penman’s Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors Is a Love Letter to Postwar Counterculture

William Harris in Jacobin:

One day in the mid-’70s on an air force base in “flattest, dullest” Norfolk, England, an African-American airmen shared some of his deep Southern blues records with a young, white English boy named Ian Penman. The meeting was more or less random, occasioned by the drift and cloistered openness of Royal Air Force family life; the music, rough and transporting, was more or less transformational. Up until then, the great love of Penman’s life was painting. Like many working-class teens in the punk and post-punk years, he appeared bound for art school. But suddenly music took the lead.

He found a record store run by a soul aficionado in the drowsy port town of King’s Lynn and fashioned a lifelong love for black American music, pop, and its subcultural tangents more generally. The sound of punk left him cold, but the culture’s radicalism lured him. Before long he’d given up on art school and begun writing for the popular music magazine that rode the postwar waves of succeeding rock styles to new heights: the New Musical Express or NME.

For some of the magazine’s historians and fans, Penman’s entrance marked the beginning of its downfall: the paper’s finger slipping from post-punk’s pulse and embracing instead an overly intellectual navel-gazing. For others, he was the greatest writer from the magazine’s greatest era, the vanishing, too-good-to-be-true years in the early English ’80s when socialist politics, French theory, and novel reveries in pop music all seemed to linger on the same corner, and to play off each other in the tossed-off pages of the same daring magazine.

More here.

A BRICS Revival?

Ana Palacio in Project Syndicate:

Ana Palacio in Project Syndicate:

There was a time when everyone was talking about a group of fast-growing emerging economies with huge potential. But the BRICS – Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa – struggled to transform themselves from a promising asset class into a unified real-world diplomatic and financial player. Is this finally changing?

The story of the BRICS begins with a November 2001 paper by Jim O’Neill, then the head of global economic research at Goldman Sachs Asset Management, called “The World Needs Better Economic BRICs” (the original grouping did not include South Africa). At a time when the world was dealing with the fallout of the dot-com bust and the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, O’Neill highlighted the BRICs’ vast potential, noting that their GDP growth was likely to accelerate considerably in the ensuing decades.

At the time, China and India were experiencing rapid economic growth, and Russia, aided by booming commodity prices, was recovering from the post-Soviet meltdown of the 1990s. Growth in the BRICs was outpacing that of the advanced economies so significantly that O’Neill predicted in 2003 that their collective GDP could overtake the then-Group of 6 largest developed economies by 2040.

While the world expected the BRICs to thrive economically, few expected them to form a united grouping. After all, they represent a mix of unsteady democracies and outright autocracies, each with its own distinctive economic structure. And two of them – China and India – have long been locked in a border dispute, with no sign of resolution.

But the BRICS saw their economic alignment as an opportunity to expand their global influence by creating an alternative to West-led international institutions. And, for a while, they seemed to be making progress.

More here.

Grey Eminence

S anjay Subramanyam in Sidecar:

anjay Subramanyam in Sidecar:

Ranajit Guha, who died recently in the suburbs of Vienna where he spent the last decades of his life, was undoubtedly one of the most influential intellectuals on the Indian left in the twentieth century, whose shadow fell well beyond the confines of the subcontinent. As the founder and guru (or ‘pope’, as some facetiously called him) of the historiographical movement known as Subaltern Studies, his relatively modest body of written work was read and misread in many parts of the world, eventually becoming a part of the canon of postcolonial studies. Guha relished the cut and thrust of intellectual confrontations for much of his academic career, though he became somewhat quietist in the last quarter of his life, when he took a surprising metaphysical turn that attempted to combine his readings of Martin Heidegger and classical Indian philosophy. This confrontational style brought him both fiercely loyal followers and virulent detractors, the latter including many among the mainstream left in India and abroad.

Guha was never one to tread the beaten path, despite the circumstances of relative social privilege into which he was born. His family was one of rentiers in the eastern part of riverine Bengal (today’s Bangladesh), beneficiaries of the Permanent Settlement instituted by Lord Cornwallis in 1793.

More here.

Psychonauts

Thomas W Hodgkinson at The Guardian:

Before writing this review, I got hold of some tiny canisters of nitrous oxide, filled a balloon or two and, watched by my bemused wife, breathed in the gas. It gave me no more of a buzz than smoking a cigarette. I must have been doing it wrong because, according to Mike Jay’s compelling history of narcotic self-exploration, it was when the chemist Humphry Davy began inhaling this newly discovered gas in Bristol in 1799, sometimes in the company of the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, that he started a revolution. While high, Davy declared that “Nothing exists but thoughts!”

Before writing this review, I got hold of some tiny canisters of nitrous oxide, filled a balloon or two and, watched by my bemused wife, breathed in the gas. It gave me no more of a buzz than smoking a cigarette. I must have been doing it wrong because, according to Mike Jay’s compelling history of narcotic self-exploration, it was when the chemist Humphry Davy began inhaling this newly discovered gas in Bristol in 1799, sometimes in the company of the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, that he started a revolution. While high, Davy declared that “Nothing exists but thoughts!”

This insight wasn’t new, of course. Bishop Berkeley had made it the cornerstone of his philosophy. Yet for Davy, it felt transformative. Another laughing gas lover, the psychologist William James, later observed that there are two types of people: the once-born and the twice-born. The once-born accept the world as it is and get on with it. The twice-born have a life-changing insight or vision. Some become questing, drug-ingesting “psychonauts” as a result – and it is they who form the focus of this fascinating book.

more here.

King: A Life

Dwight Garner at the NYT:

By this point in “King: A Life,” Eig has established his voice. It’s a clean, clear, journalistic voice, one that employs facts the way Saul Bellow said they should be employed, each a wire that sends a current. He does not dispense two-dollar words; he keeps digressions tidy and to a minimum; he jettisons weight, on occasion, for speed. He appears to be so in control of his material that it is difficult to second-guess him.

By this point in “King: A Life,” Eig has established his voice. It’s a clean, clear, journalistic voice, one that employs facts the way Saul Bellow said they should be employed, each a wire that sends a current. He does not dispense two-dollar words; he keeps digressions tidy and to a minimum; he jettisons weight, on occasion, for speed. He appears to be so in control of his material that it is difficult to second-guess him.

By the time we’ve reached Montgomery, King’s reputation has been flyspecked. Eig flies low over his penchant for plagiarism, in academic papers and elsewhere. (King was a synthesizer of ideas, not an original scholar.) His womanizing only got worse over the years. This is a very human, and quite humane, portrait.

more here.

Deepika Padukone Is Bringing the World to Bollywood

Astha Rajvanshi in Time:

Deepika Padukone never set out to take India to the world. She wanted the world to come to India. As the most popular actress in the world’s most populous country, she’s often asked if she’s going to move to Hollywood. “My mission has always been to make a global impact while still being rooted in my country,” she says on her home turf in Mumbai one humid morning in April, while on a break from shooting India’s first aerial-action film, Fighter. It’s fitting that Padukone’s photo shoot for this story is happening inside Mehboob Studios, home to some of the most legendary movies made in Hindi-language cinema, from the seminal Oscar-nominated Mother India in 1957 to Padukone’s own Chennai Express in 2013.

Deepika Padukone never set out to take India to the world. She wanted the world to come to India. As the most popular actress in the world’s most populous country, she’s often asked if she’s going to move to Hollywood. “My mission has always been to make a global impact while still being rooted in my country,” she says on her home turf in Mumbai one humid morning in April, while on a break from shooting India’s first aerial-action film, Fighter. It’s fitting that Padukone’s photo shoot for this story is happening inside Mehboob Studios, home to some of the most legendary movies made in Hindi-language cinema, from the seminal Oscar-nominated Mother India in 1957 to Padukone’s own Chennai Express in 2013.

The 37-year-old is now a legend in her own right. She has appeared in more than 30 films, won numerous awards, and generated nearly $350 million in global box-office revenues. Today, she is the highest-paid actress in India. Among her legions of fans and nearly 74 million followers on Instagram, Padukone is fondly called the Queen of Bollywood.

More here.

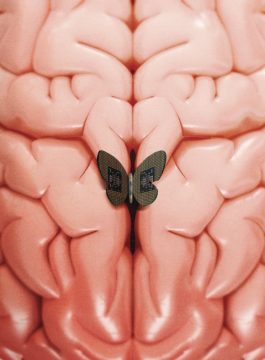

Can a brain implant treat drug addiction?

Zachary Siegel in Harper’s:

On a bright summer day in July 2021, James Fisher rested nervously, with a newly shaved head, in a hospital bed surrounded by blinding white lights and surgeons shuffling about in blue scrubs. He was being prepped for an experimental brain surgery at West Virginia University’s Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute, a hulking research facility that overlooks the rolling peaks and cliffs of coal country around Morgantown. The hours-long procedure required impeccable precision, “down to the millimeter,” Fisher’s neurosurgeon, Ali Rezai, told me.

On a bright summer day in July 2021, James Fisher rested nervously, with a newly shaved head, in a hospital bed surrounded by blinding white lights and surgeons shuffling about in blue scrubs. He was being prepped for an experimental brain surgery at West Virginia University’s Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute, a hulking research facility that overlooks the rolling peaks and cliffs of coal country around Morgantown. The hours-long procedure required impeccable precision, “down to the millimeter,” Fisher’s neurosurgeon, Ali Rezai, told me.

Prior to operating, Rezai and his team of neuroscientists created a digital rendering of Fisher’s brain, a neural map that would help them place what looked like a pair of long metal chopsticks roughly six centimeters deep into his nucleus accumbens, a structure in the center of the brain. The nucleus accumbens, according to the latest research, is associated with processing reinforcement, motivation, and desire. It’s also where the most famous neurotransmitter, dopamine, gets released when we anticipate rewards from behaviors like sex, drug use, or gambling. Rezai, who thinks as much like a neural engineer as like a surgeon, described the nucleus accumbens as the brain’s Grand Central Station, a junction for “addictions and anxiety and obsessions.”

More here.

A Response To The “Pause Letter”

Margaret Wertheim at Science Goddess:

The writers serve up a heavy dose of fear-mongering: “Advanced AI could represent a profound change in the history of life on Earth,” their second sentence declares, “and should be planned for and managed with commensurate care and resources.”

The writers serve up a heavy dose of fear-mongering: “Advanced AI could represent a profound change in the history of life on Earth,” their second sentence declares, “and should be planned for and managed with commensurate care and resources.”

I think everyone on Earth agrees AI will have to be managed with a great deal of care, yet the word “resources” might also ring some alarm bells. What the letter writers are asking for is a lot more funding for centers and programs devoted to “controlling” a problem they suggest is already bordering on a fait acompli, and which most of the authors – as AI researchers themselves – are actively involved in creating. Underlying their ‘concern’ for humanity is an inference that they are the people to get us out of the AI mess. There is a circularity to their argument which needs unpacking and begs the question of who are the people behind this missive?

more here. (h/t Lawrence Weschler)

Saturday Poem

“Sometimes ignorance is a bright shiny object”

……………………………….. —Roshi Bob

The Origin of Light

For a thousand years, the nature of light

was a source of debate, a question

that split the learned, who wondered if sight

originated as a beam coming in

from outside-the sun-or as a substance

generated inside, a stuff we shoot

out, to bathe the world and its occupants?

Curious. I never knew of this dispute

until a patient, about week before he died

of cancer, told me the story of Ali

al-Hasan, the curious man who tried

staring into the sun for as long as he

could take it. When the pain became too sharp

to stand, he understood, but it was dark.

by Jack Coulehan

—from Rattle #16, Winter 2001