by Gary Borjesson

I’ve rarely regretted holding my tongue during a session. I’ve rarely regretted drawing out what’s on a patient’s mind instead of offering some (apparently) juicy insight or interpretation of my own. Holding myself back is sometimes a matter of willpower, but mostly a matter of art. The root of this art is the Socratic method.

In broad terms, the Socratic method can be used to teach law and other technical subjects, but these aren’t psycho-therapeutic in the way that Socrates was, that Plato’s dialogues are, or that a psychotherapist is. Law professors are not examining a student’s unconscious feelings, thoughts, or beliefs. Rather, the student has taken in a teaching, and their grasp is tested by Socratic-style questioning. But Socrates and Plato themselves are concerned with making what’s latent in the mind conscious, as are psychoanalysts and other depth therapists.

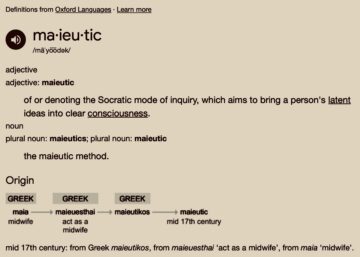

Socrates distinguishes the deeper, more therapeutic potential of his method by calling himself a midwife. This ‘maieutic’ metaphor has become synonymous with his method, as the accompanying definition shows. I want to unpack the meaning of Socratic midwifery and how this is reflected in psychotherapeutic art. The parallels are naturally of interest to me, having spent the first half of my career as a philosophy professor before leaving academia to become a psychotherapist. But more than that, the wisdom folded into the metaphor of midwifery sheds light on how to pursue an aim shared by philosophy and psychotherapy: getting to know oneself.

1. Why Midwifery

Before unpacking the metaphor, let’s consider why Socrates chose it. In simplest terms, it shows one person helping another person give birth to something within. It suggests there are times we need help to bring forth what’s growing within. Treatises, lectures, and manuals are no substitute for a therapeutic alliance when it comes to this. This is partly why Plato wrote dialogues, not treatises, and why Socrates wrote nothing at all.

We can learn a lot by reading and listening to lectures. But no teachings can help us with the specific matter of how to help this student or this patient gain self-awareness. Enter the maieutic art, which addresses the challenge of gaining the very wisdom that Socrates said made life worth living. Midwifery recognizes that the task is not to put some teaching in someone, but rather to draw something out. It also recognizes that coming to self-awareness is a more personal and fraught endeavor than, say, learning about the U.S. Constitution. Think of the shame and anger Socrates stirred by showing a prominent politician that he doesn’t know what he is talking about. The task is so fraught that Socrates was called to defend this philosophic way of life. He famously lost his case, and his life.

Psychotherapists and patients don’t usually face such peril, though a variety of harms can be suffered on both sides, and some are matters of life and death. Working with more seriously disturbed people is hard to begin with, and made harder by personal threats, legal exposure, even potential violence or suicide. In deeper therapeutic work generally, there can be sessions when you feel as though you’re walking through a minefield, bracing for explosive emotions, accusations, threats, and attacks: “You don’t care about me….You just want my money….You sit there and refuse to help me….You’re ending the session now, when I’m totally broken down? I feel like killing myself….”

No manual or technique can tell you how to handle these unique emerging situations. Just as Plato’s dialogues show us Socrates engaging differently with different people, so part of how a therapist learns how to help someone get to know themselves is…by getting to know them.

2. The Maieutic Art

So we need an art that helps us attune to the specific person—their experience, beliefs, vulnerabilities, and defenses. And because this is such personal and charged work, it helps if our art can also protect us, as far as possible, from doing or receiving harm. By calling himself a midwife, Socrates states that he’s not there to put philosophic truths into his interlocutors, but to help bring forth what lies within. Thus he invites a moment of consent. Does the politician want to have Socrates help bring to light what’s latent in his thinking? By proceeding in this way, he shows respect for the other person, while protecting himself (a little) from accusations that he’s corrupting others with his teachings.

Socrates’ method is dialectical, meaning that we get to know someone or some thing like Justice or Virtue, through dialogue guided by exploratory questioning. Likewise, psychotherapists ask questions, invite associations, draw out internal experience, and attend to verbal and nonverbal communications. All this depends on attuning to what response might be fitting to this person on this day. Socrates and the therapist assist in examining loves and hates, beliefs and opinions, values and truths. Socrates is curious: What does Callicles, the young tyrant-in-training, actually believe justice is? Does he really believe that might makes right? Does he recognize the consequences of such an opinion?

Deeper forms of education involve discovering and testing our default (often unconscious) assumptions. Socrates recognized that these are often emotionally charged and defended; unless we examine them, they will affect how we feel and think and act—with no input from us! So the midwife helps bring them to light and test whether these psychic progeny, implanted by family and society, are viable. When they prove not to be, Socrates calls them “wind eggs”, by which he means farts. Now, it’s bad enough to discover that what we thought was substantial and good is smelly hot air, but Socrates performed his midwifery in public settings, where others could observe as a prominent person is shown to be farting when they thought they were wise. Dangerous work, but not only dangerous. In other contexts, we watch Socratic midwifery draw out the noble, good heart of a young man like Glaucon, kindling in him a yearning for wisdom.

3. The Barren Midwife

Socrates deepens the metaphor with a crucial detail about himself: he is barren. He knows he is empty and ignorant, that he doesn’t have any viable wisdom of his own to offer. As countless students have protested, this is hard to believe, given how brilliantly Socrates manages every conversation. What matters, however, is that he’s proceeding as if he were barren, which is similar to how Freud thought psychoanalysts should proceed—remaining neutral themselves, prioritizing listening over speaking, and focusing attention on drawing the patient out.

There are advantages to being barren. It’s easier to focus on the person you’re trying to help if you’re not preoccupied with your own mind-progeny; and you’re not preoccupied because you’ve cultivated the mindset that you don’t have any, or at least not any you’re confident are viable. The psychoanalytic thinker Wilfred Bion is getting at a similar point when he suggests therapists enter each session with “no memory or desire” as a way to ward off intrusive influences. This is impossible of course, but it’s in line with the value of Socratic barrenness or the Buddhist’s beginner’s mind. In all three cases, we’re left empty and open, or at least cautioned about overvaluing our own progeny, and in all events warned against the temptation to put them in the patient.

Here’s the irony. We cultivate this enlightened ignorance only by getting to know ourselves. Absent this knowledge, our own unconscious material will interfere with helping others. Socrates could exercise wise discretion over his behavior and speech because he knew himself well enough that he could avoid engaging in unconscious enactments, as a modern analyst would put it. He could be fierce with some, and gentle with others, depending on what was needed—not as dictated by the vagaries of his mood or some latent need of his own. This is the power an examined life can confer. No wonder the psychoanalytic tradition makes it mandatory that you undergo analysis as part of training to become an analyst. This helps you learn about the process, but more importantly it ensures you start getting to know yourself, since this is a condition of working therapeutically with others.

I had learned a lot about the virtues of barrenness from studying Plato and from being on the faculty at St. John’s College, where our whole approach to education was Socratic. We were not professors but “tutors”, a title that announced our role was not to lecture but to help students educate themselves. Yet it wasn’t until I became a therapist that I fully appreciated the significance of barrenness for addressing unconscious communications. While these form an aspect of all of our relationships, it’s outside the scope of a professor or tutor to work with these. Imagine the (justified) uproar if I returned an essay to a student with comments that expected them to reflect on what they might ‘really’ mean, in contrast to what they actually wrote, or that criticized them for not linking their interpretation of Plato to their early childhood experience.

For psychoanalyst and patient the unconscious material becomes a master key for developing awareness and, by extension, for thinking and feeling better. Key is the right word, since unconscious contents may be repressed, compartmentalized, or otherwise locked away under the heavy guard of psychological defenses. The patient’s transference and the therapist’s countertransference exemplify how the maieutic art is at play. For example, if I pride myself on being smart and feel a patient is being competitive and outsmarting me, this could stir up my irritation, resentment, envy. This much is often inevitable. What matters, however, is whether I can recognize what’s happening for them and the feelings and the underlying complex triggered in me. If I can, then I can guard against retaliating. Having been in therapy myself, I have a tolerably clear view of what triggers me. Because I sense where those feelings are coming from, I’m less likely to retaliate by putting what belongs to me onto the patient. Or if I do, I’m quicker to recognize what’s happened and to make therapeutic use of it.

We might sum up by saying that if you want to help someone know themselves better, act as if you’re there solely to find out what lies within them. Assume that whatever is on your mind is non-viable until proven otherwise. If the midwife is not barren herself, the danger is that she will knowingly or unknowingly prefer her own mind-progeny, as mothers do. She may even try to replicate it in the other, the way the law professor seeks to implant knowledge in the student. This is not a problem if you’re studying law, but it’s obviously a problem if the aim is to help someone get to know themselves—not have them learn what you think of them, or how you think they should frame their situation, or what you think they should do with their life! The midwife trusts they have it in them, and being barren themselves isn’t tempted to try to supply it. Instead, they are curious and inquisitive and patient, or at least capable of restraint!

One of the reliable joys that come from holding my tongue is the wondrous experience of someone discovering their own heart and mind for themselves, in their own terms. Sometimes it’s similar to what I might have said, or what I did say a couple months earlier. But there’s a world of difference between someone being told who they are, and coming to know it for themselves.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.