by David J. Lobina

No, this column is not a retrospective of What’s Left? How Liberals Lost Their Way, a book by the British journalist Nick Cohen, even though the title of that forgettable volume is apposite here (I’ll come back to this below). Rather, my title is a reference to a conference that took place in Torino in 1992 under the title of What is Left?, though the post itself is meant as a revisit to Norberto Bobbio’s Destra e Sinistra (Left and Right, in its English edition), a short book from 1994 first thought up at the just-mentioned conference.

The more immediate background to Bobbio’s book, in fact, was the 1994 general election in Italy, when the post-fascist party Alleanza Nazionale (National Alliance) became part of the first Berlusconi Cabinet, the first time since the fall of Fascism that a party on the far right spectrum had entered an Italian government; this was also the background to Umberto Eco’s overtly influential (in the US) Ur-Fascism article from 1995, as discussed here and here, though this context is mostly ignored in American commentary. In a way, then, this piece is a 30-year retrospective of the 1994-95 period; a 2024-25 edition, if you like.

Bobbio’s main objective in the book, I should say, was to argue for the relevancy of distinguishing between left- and right-wing ideas at a time in Italy when many commentators did not think it meaningful any longer; this was partly due to the post-war political arrangement in the country, with the Constitution outlawing fascist parties, the centrist and conservative Christian Democrats (Democrazia Cristiana) dominating politics and society for 50 years, and the Communist Party barred from any of the many coalitions formed during that time, despite the wide support it boasted. Bobbio strove to revive the debate around left and right ideologies by approaching the dichotomy in terms of how proponents of either the left or the right position themselves towards the issue of equality (or, rather, inequality), and it is this argument that I would like to revisit here.

I doubt many people will today think there is little difference between left- and right-wing politics, certainly not in the US and the UK; that being said, some of the current political commentary, especially in the US and the UK, can be confused and even absurd as to what constitute left and right policies. I don’t think there’s much need to chronicle in any detail some of the most outlandish political comments out there at present, but suffice to say that in the US it is not uncommon to see talk of Marxist judges and professors, with the Democrats portrayed as some kind of left-wing radical party, whilst in the UK Labour under Keir Starmer, the current Prime Minister, is often described as a socialist/radical party.

It is of course ridiculous to believe that actual Marxism has any major influence anywhere in the US, at universities or in the judicial system; the accusations regarding “cultural Marxism” is but a slur these days, and Jordan Peterson clearly demonstrating (here) that he knows nothing at all about Marxism is especially telling in this regard.[i] And likewise regarding Labour-as-a-socialist-party: Starmer is in the mould of a Blairite, New Labour type, which whatever else that means, it does at least certainly mean that Labour today is not a party opposed to capitalism – and, thus, most definitely not in favour of socialism.

The reference to capitalism can get us going here. In an interesting recent paper, Chiara Cordelli characterises capitalism, broadly, as a system where the means of production are privately owned, labour is hired for money wages, and the allocation of resources is determined through markets. Less roughly, what makes capitalism distinctive (and distinctly wrong), according to Cordelli, is its mode of investment, focused as it is on reproduction, an economic cycle that is of course directed by the owners of the means of production, and clearly not by the non-owners (the workers) – the result for non-owners is that they effectively have a rather limited ability to shape the future of their own lives, thereby lacking agency in specific ways. In this sense, at the very least, capitalism is not about equal opportunities and most certainly not about equal relationships between owners and non-owners. This is where we can bring in Bobbio.

As advanced, for Bobbio the distinction between left and right is a matter of how their proponents position themselves towards equality, with those on the right generally believing that human beings are more unequal than equal, with most inequalities natural in kind and thus largely ineliminable, and those on the left mostly believing that human beings are more equal than unequal, with most inequalities social rather than natural, and thus clearly largely eliminable. In this respect, the right has a tendency to increase, or at least not decrease, the degree of inequality in a society, and is moreover always against the idea of subverting (a certain understanding of) freedom for the prospect of more equal policies.

Freedom is equally important to both left and right politics and not really definitional of either; if there is a distinction to be had along these lines, is between political freedom and authoritarianism, a dichotomy that complements, and criss-crosses, the left-and-right axis. Simplifying somewhat, and following Bobbio still, there are moderate and extremist wings on both the left and the right, which we can identify in terms of how these wings approach the ideal of freedom, with Jacobinism as an example of an extreme-left position and Fascism and Nazism as extreme-right positions, the centre-left occupied by liberal socialism (or social democracy) and the centre-right by conservatism.[ii]

This, in turn, brings another distinction under the spotlight, this time between liberalism and conservatism (or, if you must, between progressives and traditionalists), which in many ways is not as clear-cut as seems to be prima facie – consider, for instance, that capitalism is neither a liberal nor a conservative idea per se (famously, John Stuart Mill advocated a socialist kind of market economy). And there is even more ideas to throw into the mix now, such as neoliberalism, radicalism, and libertarianism. So many word-concepts!

A recent piece by Percy Anderson offers some clarity, and surprisingly so (Anderson is not always the clearest or more focused of thinkers; in recent years, and in the London Review of Books alone, he’s written very lengthy pieces about Brazil, India, and the European Union, some of it not very good)[iii]. Liberalism, to start here, and which started in France according to Anderson (he singles out Benjamin Constant, in particular), is a set of political doctrines around the right to private property, against arbitrary rule, and encompassing various individual liberties – liberty here understood in the modern sense of the word, which is to say as a freedom from external constraints or interference, and not in the ancient sense of freedom as a citizen’s active participation in public affairs, the latter a republican understanding of freedom (for what is worth, the term “liberalism” seems to have been coined in Spanish first, at the time of Spain’s 1812 Constitution, or so says Antoni Domènech in his magnum opus El Eclipse de la Fraternidad). Neoliberalism, for its part, is an economic doctrine for Anderson and not a political one, centred on cutting direct taxation, deregulating financial and labour markets, weakening trade unions, and privatising public services – an extreme take on capitalism, in some ways, and not particularly democratic.

Classical liberalism defended a rather limited suffrage, in contrast to what Domenico Losurdo calls radicalism, which advocated the equality of all men, across race and class, and thus was in favour of a universal suffrage (Losurdo identifies Mill, Marquis de Condorcet, and Immanuel Kant as radicals), the latter now a tenet of modern liberalism. Neoliberalism has been rather cavalier in this regard, though, sometimes even siding with authoritarian, far-right governments (as Anderson explains, Ludwig von Mises welcomed fascism and Friedrich Hayek favoured a small suffrage). Libertarianism, finally, has historically been a term that referred to anarchism, the latter often called libertarian socialism, in fact, but in the English-speaking world, or at least in the US, it is currently employed almost exclusively to refer to a right-wing, capitalist kind of doctrine.[iv]

To come back to Bobbio, and as alluded to earlier, he doesn’t see liberalism or libertarianism as intrinsically left or right, but as possibly one or the other depending on the context, and this is certainly right; different strands of either can be placed on various possible axes, from the left-right spectrum to the moderate-extremist continuum. There’s also a geographical component to this, with liberal political parties in countries like Italy, Spain or France clearly on the right spectrum but far more centrist in the case of the United Kingdom and Germany, with the US in an altogether different position yet again.

It’s all about the ideal of equality; or, rather, it is all about the attitude towards equality, as Bobbio insists. Equality is not an absolute ideal in any way, but a “secundum quid” ideal, a relative concept which necessitates working out what kind of rights we want to have and protect, and what kind of goods, including wealth, must be more equally shared, among whom, and under which criteria. The social liberalism typical of the left side of things would not only defend individual, economic, and political freedoms, for instance, but also social rights such as the rights to an education, to work, to health, etc. After all, the freedom a wealthy person enjoys is much greater than the freedom of a poor person and some recourse that goes beyond the minimum liberal doctrine according to which my freedom can only be curtailed insofar as it makes everyone else’s freedom compatible must be forthcoming – it is hardly equal when the rich have access to better education, health, and jobs on the sole basis of their money, position in society, and general influence.

As a matter of fact, some proponents of classical libertarianism (which is to say a kind of socialism) saw the libertarian position as a natural development of classical liberalism (anarchism as the rightful heir to liberalism, that is) precisely because of the libertarian emphasis on a positive understanding of freedom – the ability to take control of one’s life and realise one’s potential. Thus, for Wilhelm von Humboldt the ‘true end of Man [human beings, of course]…is the highest and most harmonious development of his [their] prowess to a complete and consistent whole’ (p. 10 from The Limits of State Action), a position echoed in Bertrand Russell’s Proposed Roads to Freedom, and more recently by Noam Chomsky’s vision of a society as composed of spheres of self-realisation (p. 107 from here).

All this put together, then, for Bobbio the criterion to tell left- and right-wingers apart is their differing opinions regarding the ideal of equality, and the criterion to discern between moderate and extremist positions in each case is their attitudes towards freedom, including what kind of freedom to support. As argued, right ideologies tend to emphasise what they see as natural inequalities (perhaps in terms of class, yes, but today not in terms of race or sex, at least not always explicitly), thereby overemphasising, in a way, what divides people, whilst left ideologies stress that most inequalities are social and not natural, thus focusing more squarely on what unites rather than on what divides people.

And given, moreover, that left and right tend to support different kinds of freedoms – a negative kind in terms of constraints and interference on the right, and thus focused on the rights of the individual, a positive type in terms of self-realisation on the left, with a focus on cooperation and reciprocal dependence – these differences translate into the question of whether to support capitalism or socialism – and, if so, what kind in each case.

Contemporary political discourse around left and right policies in the US and UK these days is quite different. Let us put to one side the issue of private property, that terribile delitto for Cesare Beccaria, as well as the individual freedoms of belief, speech, thought, etc.[v] For a left worth its name, the issue is not about the personal property of a given individual, their house or car; the key issue is who owns the means of production and the uses these are put to. In the context of the UK, the Labour party under Tony Blair modified Clause IV from its Party Rule Book in 1995 in order to eliminate all mention of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, a wording that clearly signalled the socialist ambition of the party up to that point, to be replaced for a democratic socialism defined solely in terms of a common set of values. This turned New Labour, for this was the rebranding at the time, into a centrist party, and even though the aspiration of New Labour to decrease some inequalities in the UK did distinguish it from the Conservative party, Blair’s transformation has survived to this day and calling contemporary Labour a left-wing party is a bit de trop – there is no intention to even reform capitalism, let alone subvert it.

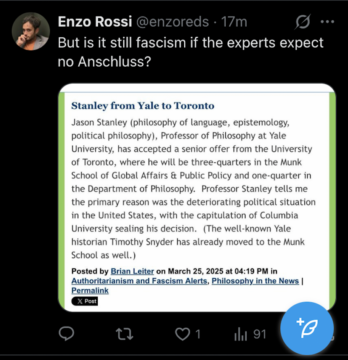

In the US, on the other hand, most of the talk on the supposed left side of politics is not even about equality, but about equity, the latter a concept to do with representation of different groups (in terms of race, sex/gender, etc.) in businesses, government, etc. in proportion to their existence in the general population, which in the event has mostly involved micro-interventions here and there to produce a more ethnically diverse elite. This has had the effect of replacing the issue of class with that of identity, and to leave inequality in the US mostly unchanged. Even though such trends are painted as progressive and therefore part of the left, the political theorist Enzo Rossi calls such positions more accurately as a case of radical liberalism (radlibs, he calls them on Twitter/X) and not a left undertaking, with Brian Leiter arguing that these trends are part of a neoliberal enterprise – as for the Democratic party, it is simply an aberration to see them as a left-wing party in a way, and here too Leiter is spot-on when he calls Democrats the prudent wing of the capitalist class.[vi]

Let us circle back to Chiara Cordelli’s article on capitalism to bring this long piece to an end. As explained earlier, in her article Cordelli argues that the most distinctive wrong of capitalism is that it makes most workers and citizens unfree (in addition to exploiting many workers, of course) in that most citizens lose agency over their own future under capitalism, the result of vastly unequal relationships in capitalist societies. In these very terms, Cordelli sees socialism as a project of reconciliation, a way for citizens to reappropriate their world; that is, disalienation as the right to share in the creation of one’s future along with that of one’s society, as Cordelli puts it, and this naturally means doing something about the ownership of the means of production, the sine qua non of doing away with inequality.

So there you have it, then: it is not really a left movement if capitalism is mostly left alone, and it is also not really a left movement if equality is also mostly left alone.

[i] It is really astonishing to see an academic humiliate themselves so thoroughly as Peterson did in this event, a debate with the philosopher Slavoj Žižek. He started the debate by admitting that he hadn’t really read anything from Marx (or from Žižek) and then proceeded to give a sophomoric commentary on The Communist Manifesto, the shortest writing he was probably bothered to read for the event.

[ii] Ah, fascism. I of course exclusively mean the inter-war phenomenon in 1920-40s Europe by this term, and in particular the Italian kind, with militia-parties, extreme use of violence in the streets, anti-everything attitude, and the totalitarian intent to create a new Italy and new Italians as the main features. I most certainly do not think Trumpism has anything to do with fascism, despite the crude and manipulative generalisations by commentators such as Timothy Snyder and Jason Stanley (neither of these are actually experts on fascism, and one of them is fast becoming a charlatan, see here). Trumpism is more a combination of a mafia-style mentality (this post is from 2016, the Guardian is late to the party here), patrimonialism, and anarcho-capitalism, with the addition of a rather American strand of Christian nationalism – in fact, Trumpism is a very American phenomenon, full stop, even if authoritarian. The use and abuse of the term “fascism” is becoming shambolic by now; see, for one of the worst things I have read this year, Sophie Lewis’s shameful accusation that some feminists are enabling fascism, echoing Judith Butler’s equally execrable take on the matter.

[iii] A friend of mine and I used to joke that every time Anderson was eyeing a new holiday he would sit down and type out a long piece for the LRB on whatever topic took his fancy at the time (NB: the LRB is well-known for paying contributors rather well; lucky if you can get it).

[iv] I should add that this is also true of liberalism, as this concept very often receives different interpretations across Europe and the US (see, for instance, this exchange between European and American scholars on liberalism and socialism). In fact, I could write a whole entry on 3QD entitled “Liberalism, Libertarianism, Fascism: Americans, give us back our word-concepts!”, and maybe I will.

[v] In a 1957 article on what the left and the right share and do not share, which Bobbio references approvingly in his book, Luigi Einaudi stresses that left and right ideologies are indeed in agreement regarding individual freedoms in addition to accepting the need for the state to intervene in the economy as well as in many other domains; what they don’t agree on is in relation to the ideals of equality and liberty, to labour the point I have been making here.

[vi] This, in addition, pinpoints Cohen’s hopelessness in relating the left and liberals in the title of the forgotten book of his I cited in the incipit.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.