by Rafaël Newman

I have always been tall. Or rather, I have been aware of my above-average height since puberty, when freakish physical change kicks in, mischievously, in concert with enhanced self-consciousness. At age 14 I moved with my mother and siblings from the Vancouver suburbs to midtown Toronto, where the students at my new high school, not having witnessed my incremental growth over the past years, promptly dubbed me “Gi-Raf”. Later, at the farther end of teenagerhood, I entered a sports supply store in Paris and immediately banged my head against a bicycle frame suspended from the low ceiling—whereupon the shopkeeper looked up and said reproachfully: Monsieur, vous n’avez pas la taille réglementaire! (“Yours are not the standard dimensions, sir!”) And when, during that same period, my viability as a potential romantic match—at least, as measured by traditional chronology— had become a matter for unabashed public comment, I was so often lauded for my stature by diminutive Ukrainian and Polish relatives that I came to understand height as chief among the Jewish erogenous zones. I had evidently become a paragon of my people!

In this last regard I had had a leg up, as it were. My father, the scion of his émigré Eastern European clan, had chosen his mate not from the large community of similarly transplanted Ostyidden inhabiting his native Montreal, but had instead married the daughter of a non-Jewish German immigrant. Wilhelm Alfred “Franz” Kornpointner—my grandfather-to-be—had been tall and shapely enough as a young man to attract the Weimar-era health authorities, which (according to family legend) commissioned a photo shoot to produce a normative example of Bavarian manhood.

Thus I owed my dimensions to my parents’ exogamous union; and these dimensions, in turn, earned me the attention of my paternal Jewish relatives. Such attention, of course, was not always only pleasant, despite my natural extroversion, since it sometimes seemed to bespeak as much envy as admiration. And, since envy is notoriously the harbinger of occasionally lethal resentment, I would habitually ward off the potential Evil Eye with a peculiar ritual: by re-imagining myself in a series of unflatteringly over-sized or out-of-place roles. There was for example the Shabbos goy, the humble gentile who helps his Jewish neighbors accomplish the tasks they are forbidden to perform on a holy day; this also allowed me to embellish the melancholy fact that I was not, halachically speaking, a proper Jew at all. Then there was the Golem, the anthropoid helpmate fashioned out of clay by the legendary Rabbi Löw of Prague, which turns against its creator and was an ancestor of the Frankenstein story—a murderous blessing for my psychological household, which could thus combine its apotropaic gesture with a fantasy of revenge on those who had excluded me. And finally, most grotesque of all, if also most expressive of my ambivalent wish to be accepted as a fully-fledged member of my father’s tribe, there was my reincarnation as The Jewish Giant.

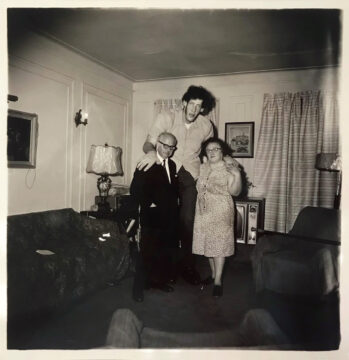

Eddie Carmel, who was born Oded Ha-Carmeili in Mandate Palestine in 1936 and who died in 1972 in the Bronx, suffered from a pituitary disorder known as acromegaly, or gigantism, which involves excessive production of growth hormone. Carmel grew to be well over 7 feet tall during his brief lifetime, and pursued a variety of careers, including as “entertainer.” In this last capacity he was known as “The Happy Giant,” “The World’s Biggest Cowboy,” and “The Jewish Giant,” and was immortalized by the American photographer Diane Arbus in Jewish Giant, taken at home with His Parents in the Bronx, N.Y., 1970, a picture I had seen in a collection of Arbus’s photographs on my parents’ bookshelf.

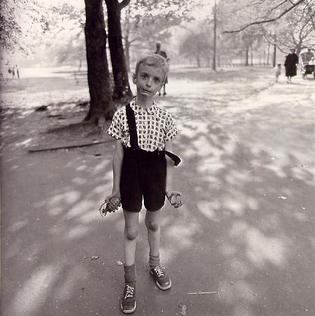

(Diane Arbus, whose documenting of everyday American proletarian homeliness was at once fascinating and repellent to a Canadian from a leftwing milieu, and whose death by her own hand added to her melancholy mythos, occupied an unusually influential place in my imagination in 1980s Toronto. For instance, Josh, my best friend at high school, added to his allure by claiming to have been the boy with the plastic hand grenade in Central Park, another of Arbus’s celebrated grotesques. And it did all sort of add up, what with his dad having been a Vietnam War resister from New York now teaching sociology at a Toronto university, and the portraited boy’s proto-punk energy clearly still fizzing around in Josh, who introduced me to Buzzcocks and the Pistols and vainly insisted I cut my hair before we attended a performance by the Ramones at Harbourfront in 1979. I refused, and was subsequently vindicated when I saw that Joey Ramone—born Jeffrey Ross Hyman and a Jewish giant in his own right—wore his locks even longer than mine.)

Now, not long ago, but decades after my internalized cosplay at my Bubbi and Zaideh’s house, I began to suffer from dizzy spells. The vertigo was so intense that it caused me to weave drunkenly, especially late at night, and cling to door jambs for support—an unpleasant reminder of a long-gone bibulous youth. I consulted my family physician, Dr Lorger, who sent me to an ENT specialist. This second physician, Dr Gut, diagnosed benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, or BPPV, a mechanical disorder of the inner ear treatable with a simple, if nauseating, home remedy known as the Epley maneuver. Nevertheless, since my involuntary eye movements, during an episode induced in her examining room, were slightly abnormal, Dr Gut sent me further, for an MRI of the head. This procedure, akin to being tied to the train tracks à la Perils of Pauline, was negative for vertiginous brain damage—but it did produce an “incidental finding,” the presence of a Hypophysenadenom, or cyst on the pituitary gland.

For evaluation of this alarming new development I was next dispatched to a neurosurgeon at Hirslanden, a local medical center. Dr Bernays was a cultured elderly professor whose office hours routinely ran overtime, as I learned when my own delayed appointment was interrupted by his receptionist informing him that there were other patients awaiting his attentions. He was happy to discuss his father’s work as a translator of Homer, as well as his descent from a collateral line of the same illustrious Ashkenazi family into which Freud had married, and which includes Isaac Bernays, an esteemed 18th-century Chief Rabbi of Hamburg, as well as Edward Bernays, a pioneer in the field of public relations. My neurosurgeon also eventually gave me his opinion of my condition, based on his reading of the MRI results and my puzzled responses to questions regarding recent changes in my shoe size and my difficulty removing rings from my fingers. Dr Bernays’s suspicion was that I was suffering from acromegaly, otherwise known as gigantism: the very same hypertrophied growth hormone production that had afflicted Eddie Carmel, and which had served me in my youth as an apotropaic joke.

Had I been The Jewish Giant all along, then? The Mayo Clinic lists the following symptoms of acromegaly, with the caveat that they “tend to vary from one person to another”:

Enlarged hands and feet.

Enlarged facial features, including the facial bones, lips, nose and tongue.

Coarse, oily, thickened skin.

Excessive sweating and body odor.

Small outgrowths of skin tissue (skin tags).

Fatigue and joint or muscle weakness.

Pain and limited joint mobility.

A deepened, husky voice due to enlarged vocal cords and sinuses.

Severe snoring due to obstruction of the upper airway.

Vision problems.

Headaches, which may be persistent or severe.

Menstrual cycle irregularities in women.

Erectile dysfunction in men.

Loss of interest in sex.

As it happens, I exhibit roughly half of these (I’m not saying which half); so it seemed like a toss-up. Accordingly, and following our charming genealogico-philological discussion, Dr Bernays dispatched me to two further physicians: a neurologist, Dr Vogel, to confirm Dr Gut’s original finding of BPPV; and Dr Faulenbach, at the Hormonzentrum Zürich, to have my hormone levels tested.

In the days that followed and as I awaited this final examination, I shared my provisional diagnosis with select confidantes. Their responses ranged from frank horror, through guarded amusement, to attempts at preemptive consolation for a possible hormonal imbalance. This last tactic, however well-meaning, was not always salutary. When one of my friends fondly referred to me as “The BFG,” for instance, in reference to the title of Roald Dahl’s celebrated young adult novel featuring a Big Friendly Giant, the sobriquet reminded me instead of the BunchoFuckinGoofs, or BFGs, a Toronto hardcore band whose members had lived next to the apartment I shared with a girlfriend in Kensington Market in the 1980s and whose squat, its windows blinded with balled-up underpants, was reputed to be protected by handguns and Doberman Pinschers. And this proximity, despite my own continued allegiance to the (mostly British) punk music of my adolescence, had been an unpleasant reminder of the potential for violence inherent in that genre.

But what most disturbed me at the prospect of this next round of tests was a memory triggered from even further back in my life, from the period of my prepubescence. A child of the 1960s who came of age on Canada’s hippy-dippy west coast, I began early on to wear my hair long, which, combined with relatively delicate facial features, gave me a feminine appearance—and thus for a long time I was mistaken for a girl. On my first solo airplane flight, for instance, at age 11, already mortified by the Unaccompanied Minor (UM) documents pouch slung around my neck, I reported to a flight attendant that I was feeling nauseated—at which the kindly woman leaned closer to me and asked, sotto voce: “Have you had your period yet, dear?” (My physiognomy has also been memorably interpreted, by an algorithm, as that of a canine: but that is another story.)

Later on, in early teenage-hood, when masculine traits were just beginning to manifest in my body, while my still shoulder-length hair rendered me unsettlingly epicene, I was teased, harassed, and occasionally beaten by schoolmates for failing to conform to gender norms. In fact, even at American graduate school in my twenties, among relatively enlightened colleagues and in a burgeoning atmosphere of radically realigned thinking about sex, orientation, and gender(s), I was still mocked, if ever so genteelly, for resembling a “giant female hockey player”—which economically united my twin freakishnesses (excessive height and gender indeterminacy) while also ironically calling attention to the fact that I was profoundly uninterested in the national sport of my Canadian homeland: and thus a treble oddity.

In the meantime, of course, certain other undeniable “secondary sex characteristics”—such as a deep voice, facial hair, and, perhaps most strikingly, my height—have developed to render me easily “legible” as a man, despite the long hair I have worn pretty consistently all my life (with a brief period of shaven-headed protest in the early nineties). Furthermore, I have also read Paul B. Preciado on the modern “invention” of hormones as a communications system susceptible both to the sinister manipulations of the “pharmacopornographic” industry and to individual experimentation in protest against a repressive biopolitics: so I have become pretty relaxed about being “misgendered,” something that hasn’t happened for decades now anyway.

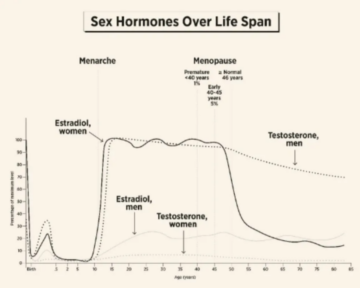

However, last month, just as I was awaiting my call-up to the Hormonzentrum for testing, I also happened to be reading All Fours, Miranda July’s absorbingly neo-punk novel of perimenopause. And so I was vividly aware of human hormonal vicissitudes and their unequal distribution between the biological sexes (which are considered to be just two in number on the chart by which the narrator is plagued, a further provocation given her fierce commitment to a non-binary child):

For July’s protagonist, approaching 50 and just beginning to sense a change in her hormonal household, the female sexual experience resembles a cliff, whereas men suffer only a gentle and gradual tapering off in their sex drive. Now, this offered me some consolation when I studied the chart myself (recall the libidinal symptoms of my still unconfirmed acromegaly), not to mention a certain schadenfreude—until I realized that the results I was awaiting from the Hormonzentrum would likely include an account of my sexual hormones in addition to those responsible for growth.

What, then, if my environment had been sensing the truth about me all along: that flight attendant in 1975, my primary school classmates, my graduate school colleagues? What if they had known something I have only glancingly suspected about myself: that I am neither completely masculine nor completely feminine? That I am, as my brother is fond of joking, a product of a mixed marriage: between a man and a woman? For, despite a feminist upbringing and a post-gender enlightenment, my own early struggle to assert my “masculinity” according to the antiquated norms of my youth has left me with anxieties about my sexual identity not easily allayed by subsequent biography, and all too quickly aroused by application of the scientific method.

As it turned out, the results I eventually received from the Hormonzentrum were “normal”—that is, no sign of acromegaly (Insbesondere findet sich laborchemisch kein Hinweis für eine manifeste Akromegalie), and presumably no sexual “irregularity” either. At any rate, the only recognizable steroid hormone mentioned in the lab report, at a level typical for my cohort, is testosterone (or, as it’s known in Switerland, Testoblerone: badabing). And what would my place on the sex-gender-sexuality spectrum matter anyway, at this late stage? An “atypical” position might even restore to me some of the radical cachet lost to my otherwise humdrum hegemonic identity—as a white, heterosexual, North American cis-male of European descent—since the revelations of settler Canada’s despicable treatment of indigenous children, and the worldwide excoriation of “the Jewish state”.

I am therefore, it seems, simply a man in late middle age deserving of the standard prescriptions—for weight loss and increased movement, that is, and no more. Not for hormone replacement therapy, nor for the introduction into my nose of an implement to slice off the cyst (now ruled quite benign) on my pituitary gland: a surgery the affable Dr Bernays had chillingly said he would be “happy” to perform.

I do, however, remain tall. And to this day I wear my hair very long, and now sport earrings in both ears, which accoutrements lend me, I suppose, an air of fluidity, as well as, perhaps, further obscuring the Jewishness in my heritage. This last, indeterminate feature might be better, if more uncannily, highlighted were my last name to be more distinctly Judaic—something like Rosenblatt or Greenbaum—rather than the surname I bear, the ecumenical, Everyman moniker of Catholic cardinals and blue-eyed movie stars. Still, my parents, ostensibly in memory of my great-aunt Dora but also, perhaps, in a subconsciously apotropaic gesture of their own, to ward off the Evil Eye of assimilation, gave me as a middle name David—the famously shapely and hypermasculine, if also infamously diminutive and bellicose, King of the Jews.