Jeffrey Meyers at Salmagundi:

Sylvia Plath is the Diane Arbus of poetry, the verbal equivalent of her visual art. Since Arbus and Plath had strikingly similar lives, it’s surprising that they never mentioned each other and that their biographers have not compared them. They were self-destructive sexual adventurers, angry and rebellious, driven and ambitious. Both suffered extreme depression, had nervous breakdowns and committed suicide. But they used their mania to deepen their awareness and inspire their art, and created photographs and poetry to impose order on their chaotic lives. They shared an ability to combine the ordinary with the grotesque and monstrous, and expressed anguished feelings with macabre humor. Arbus was consciously and deliberately bohemian, Plath outwardly conventional yet inwardly raging. Both explored the dark side of human existence and revealed their own torments.

Sylvia Plath is the Diane Arbus of poetry, the verbal equivalent of her visual art. Since Arbus and Plath had strikingly similar lives, it’s surprising that they never mentioned each other and that their biographers have not compared them. They were self-destructive sexual adventurers, angry and rebellious, driven and ambitious. Both suffered extreme depression, had nervous breakdowns and committed suicide. But they used their mania to deepen their awareness and inspire their art, and created photographs and poetry to impose order on their chaotic lives. They shared an ability to combine the ordinary with the grotesque and monstrous, and expressed anguished feelings with macabre humor. Arbus was consciously and deliberately bohemian, Plath outwardly conventional yet inwardly raging. Both explored the dark side of human existence and revealed their own torments.

more here.

Katia and Maurice Krafft were both born in the 1940s in the Rhine valley, close to the Miocene Kaiser volcano, though they didn’t know each other as children. They met on a park bench when they were students at the University of Strasbourg, and from that moment on, according to their joint obituary in the Bulletin of Volcanology, ‘volcanic eruptions became the common passion to which everything else in their life seemed subordinate’. They married in 1970, formed a crack team of volcano-chasers, équipe volcanique, and set off to get as close as they possibly could to the very edge of every fiery crater, to collect samples and data and just to be there, ecstatic with the enormity of it all, like a pair of mad moths drawn into a candle flame.

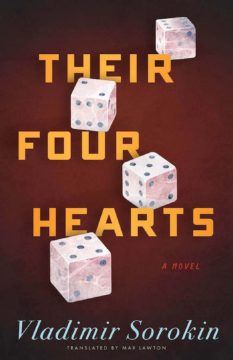

Katia and Maurice Krafft were both born in the 1940s in the Rhine valley, close to the Miocene Kaiser volcano, though they didn’t know each other as children. They met on a park bench when they were students at the University of Strasbourg, and from that moment on, according to their joint obituary in the Bulletin of Volcanology, ‘volcanic eruptions became the common passion to which everything else in their life seemed subordinate’. They married in 1970, formed a crack team of volcano-chasers, équipe volcanique, and set off to get as close as they possibly could to the very edge of every fiery crater, to collect samples and data and just to be there, ecstatic with the enormity of it all, like a pair of mad moths drawn into a candle flame. ALTHOUGH VLADIMIR SOROKIN has earned his reputation as Russia’s premier satirist, he deserves more credit for being among its finest metaphysicians. In Russia, as the saying goes, fiction is philosophy. Though very few Russian philosophers have established a position for themselves in the Western canon, the particularities of Russian thought still find their way into the global imagination through the work of literary greats like Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. Sorokin, known as much for his stylistic range as for his prescient depictions of Russia’s shifting sociopolitical tides, is a standard-bearer in this venerable tradition.

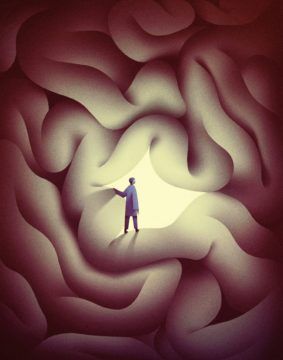

ALTHOUGH VLADIMIR SOROKIN has earned his reputation as Russia’s premier satirist, he deserves more credit for being among its finest metaphysicians. In Russia, as the saying goes, fiction is philosophy. Though very few Russian philosophers have established a position for themselves in the Western canon, the particularities of Russian thought still find their way into the global imagination through the work of literary greats like Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. Sorokin, known as much for his stylistic range as for his prescient depictions of Russia’s shifting sociopolitical tides, is a standard-bearer in this venerable tradition. It was the first in

It was the first in Even if you do manage to pick up a book, you might feel lingering guilt if it isn’t an important book, or at least an improving one. “There is no such thing as the correct book to read,” Allison Escoto reminded me over Zoom, a bookcase looming behind her. Escoto is the head librarian and education director at the Center for Fiction in Brooklyn. The canon of “important books” — what they are, and who gets to choose them — has been in a vibrant state of reexamination and expansion in recent years, she reminded me, and that means the “notion of the correct book, or the right book, or the acceptable book is itself under scrutiny.”

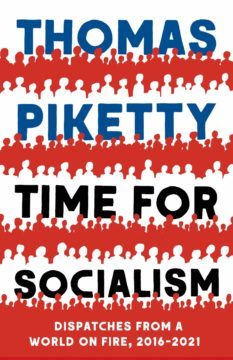

Even if you do manage to pick up a book, you might feel lingering guilt if it isn’t an important book, or at least an improving one. “There is no such thing as the correct book to read,” Allison Escoto reminded me over Zoom, a bookcase looming behind her. Escoto is the head librarian and education director at the Center for Fiction in Brooklyn. The canon of “important books” — what they are, and who gets to choose them — has been in a vibrant state of reexamination and expansion in recent years, she reminded me, and that means the “notion of the correct book, or the right book, or the acceptable book is itself under scrutiny.” Saint Domingue was the crown jewel of the French empire in the Caribbean when its slaves rebelled in 1791. They formed the independent republic of Haiti in 1804, but the terms of the island’s separation from France was contested long thereafter, and French reconquest loomed. In 1825, in order to secure their sovereignty, the Haitians were forced (in the words of Charles X’s decree) « to compensate the former colonists who may claim an indemnity » for the human property that had been lost. The total sum of these reparations was 150 million golden francs, which the new Caribbean nation funded through a massive loan, paid back slowly over decades. Generations of Haitians – deep into the twentieth century – contributed a significant portion of their livelihood to support the descendants of those who had kidnapped their ancestors from Africa in the hundreds of thousands and forced them to labor under genocidal conditions.

Saint Domingue was the crown jewel of the French empire in the Caribbean when its slaves rebelled in 1791. They formed the independent republic of Haiti in 1804, but the terms of the island’s separation from France was contested long thereafter, and French reconquest loomed. In 1825, in order to secure their sovereignty, the Haitians were forced (in the words of Charles X’s decree) « to compensate the former colonists who may claim an indemnity » for the human property that had been lost. The total sum of these reparations was 150 million golden francs, which the new Caribbean nation funded through a massive loan, paid back slowly over decades. Generations of Haitians – deep into the twentieth century – contributed a significant portion of their livelihood to support the descendants of those who had kidnapped their ancestors from Africa in the hundreds of thousands and forced them to labor under genocidal conditions. Almost as soon as it was floated in 1965 by Harvard psychiatrist Joseph Schildkraut, the serotonin hypothesis of

Almost as soon as it was floated in 1965 by Harvard psychiatrist Joseph Schildkraut, the serotonin hypothesis of  Term limits or other

Term limits or other

Grief is painful. We all know that. But Is there a “good grief”? Eminent essayist and man of letters

Grief is painful. We all know that. But Is there a “good grief”? Eminent essayist and man of letters  It wasn’t until my mid-forties that I began to write about the world of medicine. Before that, I was busy building a career as a hematologist-oncologist: caring for patients with blood diseases, cancer, and, later, aids; establishing a research laboratory; publishing papers; training junior physicians. A doctor’s workload tends to crowd out everything but the most immediate concerns. But, as the years pass, the things you’ve pushed to the back of your mind start to pile up, demanding to be addressed. For two decades, I had seen my patients and their loved ones face some of life’s most uncertain moments, and I now felt driven to bear witness to their stories.

It wasn’t until my mid-forties that I began to write about the world of medicine. Before that, I was busy building a career as a hematologist-oncologist: caring for patients with blood diseases, cancer, and, later, aids; establishing a research laboratory; publishing papers; training junior physicians. A doctor’s workload tends to crowd out everything but the most immediate concerns. But, as the years pass, the things you’ve pushed to the back of your mind start to pile up, demanding to be addressed. For two decades, I had seen my patients and their loved ones face some of life’s most uncertain moments, and I now felt driven to bear witness to their stories. CHILE’S VILLARRICA NATIONAL PARK—

CHILE’S VILLARRICA NATIONAL PARK— For many generations in societies shaped by Christianity, monogamy has been the almost undisputed champion of relationship norms. In Britain and the US, it has been held up as the dominant – really the only – ideal for serious romantic partnerships, toward which all of us should always be striving. According to the authors of a 2019 article in Archives of Sexual Behavior, focused on the US context, a “halo surrounds monogamous relationships . . . monogamous people are perceived to have various positive qualities based solely on the fact they are monogamous.” Other relationship models, or even just being persistently single, have often been seen as suspect, if not morally wrong.

For many generations in societies shaped by Christianity, monogamy has been the almost undisputed champion of relationship norms. In Britain and the US, it has been held up as the dominant – really the only – ideal for serious romantic partnerships, toward which all of us should always be striving. According to the authors of a 2019 article in Archives of Sexual Behavior, focused on the US context, a “halo surrounds monogamous relationships . . . monogamous people are perceived to have various positive qualities based solely on the fact they are monogamous.” Other relationship models, or even just being persistently single, have often been seen as suspect, if not morally wrong. Germans call it

Germans call it  Published in 1953, The Captive Mind remains possibly the best book ever written about the lure and trap of totalitarian ideology. In his riveting collection of linked essays, the great poet Czesław Miłosz probed the motivations of Polish writers and intellectuals (Miłosz, at one time, included) who joined the Communist regime after World War II. The rewards of the book begin with its epigraph, which Miłosz attributes to “An Old Jew of Galicia”:

Published in 1953, The Captive Mind remains possibly the best book ever written about the lure and trap of totalitarian ideology. In his riveting collection of linked essays, the great poet Czesław Miłosz probed the motivations of Polish writers and intellectuals (Miłosz, at one time, included) who joined the Communist regime after World War II. The rewards of the book begin with its epigraph, which Miłosz attributes to “An Old Jew of Galicia”: