Louis Rogers in Sidecar (image by Carlo.benini – Own work):

Louis Rogers in Sidecar (image by Carlo.benini – Own work):

In 2015, the American writer Jhumpa Lahiri published an essay in The New Yorker titled ‘Teach Yourself Italian’. Proceeding in a present tense of terse sentences, it detailed Lahiri’s relationship with the Italian language – an ‘infatuation’, which at various stages of her life she had pursued for ostensibly practical reasons: a doctorate on Italian architecture in English Renaissance drama; a holiday; a book tour. Finally compelled to relocate to Rome, Lahiri describes how she soon began writing in Italian, renouncing the language in which she had enjoyed a successful career as a writer ever since her Pulitzer-winning debut Interpreter of Maladies (1999). The essay’s conceit comes in the penultimate paragraph, where Lahiri notes in passing that she is ‘writing this sentence in Italian’. An editorial note confirms the article had indeed been translated. Lahiri’s journey into Italian was thus certified; for her English readers, she was now on the other side of a gauze.

Lahiri subsequently returned to the United States to take up a professorship at Princeton, but her work has remained – both linguistically and intellectually – on foreign shores. She writes her literary work in Italian, sometimes translating herself, while any writing in English takes the form of criticism and translations of Italian and Latin writing. This striking and unusual new course has however remained hard to make clean sense of, or, perhaps, to narrativise. A memoir, In Other Words (2015), written in Italian and published in a bilingual edition, gives a vivid sense of Lahiri’s experience of living in Italy and Italian, as well as what writing in another language has offered her – namely a freedom which is paradoxical, both permissive and restricting. Yet what drove her decision, and what sustains it, is left tantalisingly unarticulated.

More here.

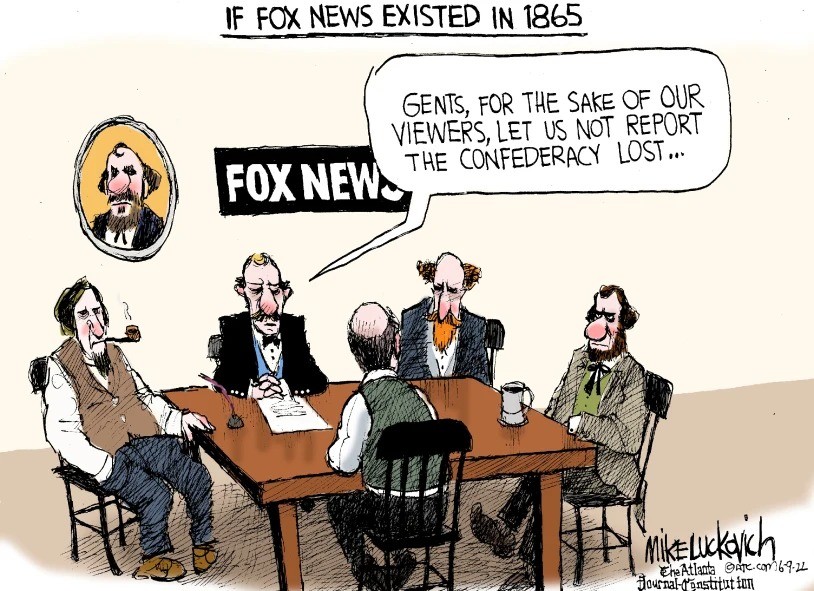

So now we can answer the question: How does democracy die? It dies not in darkness, as the Washington Post’s Trump-era slogan would have it, but in the White House itself, in the private dining room off the Oval Office, with the sound of Fox News blaring in the background. That private dining room was

So now we can answer the question: How does democracy die? It dies not in darkness, as the Washington Post’s Trump-era slogan would have it, but in the White House itself, in the private dining room off the Oval Office, with the sound of Fox News blaring in the background. That private dining room was  We are all going to die. Most of us don’t know when. But what if we did know? What if we were told the year, the month, even the day? How would that change our lives? These questions drive Nikki Erlick’s debut novel, “The Measure,” which weighs Emerson’s claim that “it is not the length of life, but the depth of life” that matters.

We are all going to die. Most of us don’t know when. But what if we did know? What if we were told the year, the month, even the day? How would that change our lives? These questions drive Nikki Erlick’s debut novel, “The Measure,” which weighs Emerson’s claim that “it is not the length of life, but the depth of life” that matters. We have seen nothing yet. The dangerous heat England is suffering at the moment is already

We have seen nothing yet. The dangerous heat England is suffering at the moment is already  Humans have been expressing thoughts with language for tens (or perhaps hundreds) of thousands of years. It’s a hallmark of our species — so much so that scientists once speculated that the capacity for language was the key difference between us and other animals. And we’ve been wondering about each other’s thoughts for as long as we could talk about them.

Humans have been expressing thoughts with language for tens (or perhaps hundreds) of thousands of years. It’s a hallmark of our species — so much so that scientists once speculated that the capacity for language was the key difference between us and other animals. And we’ve been wondering about each other’s thoughts for as long as we could talk about them. In her new book, The Bin Laden Papers, Nelly Lahoud, a senior fellow at New America, has gone through the huge collection of information purloined by Navy Seals in their 2011 raid on Osama bin Laden’s hideout, information that was declassified in 2017. The book essentially concludes that Carle had it right. Although “falsely” taken to be “a Leviathan in the jihadi landscape,” she says al-Qaeda has actually been notable mainly for its “operational impotence” while bin Laden, its fabled, if notorious, leader, continued to pursue “alarmingly sophomoric” goals and was “powerless and confined to his compound, over-seeing an ‘afflicted’ al-Qaeda.”

In her new book, The Bin Laden Papers, Nelly Lahoud, a senior fellow at New America, has gone through the huge collection of information purloined by Navy Seals in their 2011 raid on Osama bin Laden’s hideout, information that was declassified in 2017. The book essentially concludes that Carle had it right. Although “falsely” taken to be “a Leviathan in the jihadi landscape,” she says al-Qaeda has actually been notable mainly for its “operational impotence” while bin Laden, its fabled, if notorious, leader, continued to pursue “alarmingly sophomoric” goals and was “powerless and confined to his compound, over-seeing an ‘afflicted’ al-Qaeda.” CLAES OLDENBURG IS THE SINGLE Pop artist to have added significantly to the history of form. In order to perceive this, however, one must look beyond the Rabelaisian absurdity of his grotesque imagery to the inventiveness of his shapes, techniques, and materials. These are sufficiently original to identify Oldenburg, not, as he has erroneously been seen, as a chef d’ecole of Pop art, but as one of the most vital innovators in the field of contemporary sculpture, whose vision has affected the work of many other young artists of his generation.

CLAES OLDENBURG IS THE SINGLE Pop artist to have added significantly to the history of form. In order to perceive this, however, one must look beyond the Rabelaisian absurdity of his grotesque imagery to the inventiveness of his shapes, techniques, and materials. These are sufficiently original to identify Oldenburg, not, as he has erroneously been seen, as a chef d’ecole of Pop art, but as one of the most vital innovators in the field of contemporary sculpture, whose vision has affected the work of many other young artists of his generation. After 20 years spent recovering long-lost artifacts and priceless art from across the globe, Dutch art detective Arthur Brand thought his career had peaked. He wondered how any case could top those that turned up a stolen Picasso or the pair of bronze horses made for Adolf Hitler once believed to have been destroyed by the Soviet army.

After 20 years spent recovering long-lost artifacts and priceless art from across the globe, Dutch art detective Arthur Brand thought his career had peaked. He wondered how any case could top those that turned up a stolen Picasso or the pair of bronze horses made for Adolf Hitler once believed to have been destroyed by the Soviet army.

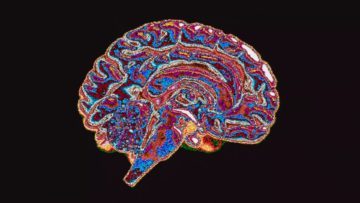

Many of the things that you believe right now—in this very moment—are utterly wrong.

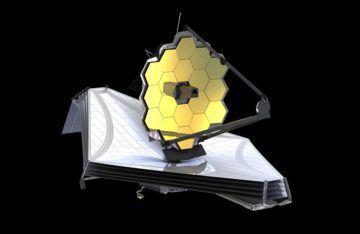

Many of the things that you believe right now—in this very moment—are utterly wrong. Scientists are reporting that damage sustained to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) during a micrometeoroid strike in late May 2022 may be worse than first thought.

Scientists are reporting that damage sustained to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) during a micrometeoroid strike in late May 2022 may be worse than first thought. Ms. Koo wondered whether people who started out at the bottom and achieved high status would support public policies to assist other strivers like themselves. Or, having successfully climbed the socioeconomic ladder, would they perceive upward social mobility as less difficult? “If I did it, why can’t they do it?” Ms. Koo asked rhetorically.

Ms. Koo wondered whether people who started out at the bottom and achieved high status would support public policies to assist other strivers like themselves. Or, having successfully climbed the socioeconomic ladder, would they perceive upward social mobility as less difficult? “If I did it, why can’t they do it?” Ms. Koo asked rhetorically.