This is a Political Poem

Three people stand in a shop in Paris looking

at an old piano. It might have been played by

Beethoven. The veneer is sumptuous, though

blistered where separated from the shaping

pieces. Inside, no cast-iron frame, but thick,

wooden struts. The woman attempts a scale, but

many of the notes are missing. “It’s like trying

to capture moonlight in a net.” The man marvels

at the piano’s age and that it had been made

entirely by hand. The shop owner tells them,

“The trees for the wood were most likely planted

in the late sixteenth century. The woodworking

guilds of Germany planted trees so their children’s

children’s children would have the right kind of wood

harvested, sometimes, 250 years later. Then it was

cured from 10 to 40 years. Even in the nineteenth century,

such wood was rare, but now it is a substance

that has gone out of the world we live in.”

by Nils Peterson

Author’s note: This poem is gathered from a few pages of Thad Carhart’s

fine book “Piano Shop on the Left Bank”.

Early in her book about John Keats, Lucasta Miller calls Lord Byron an “aristocratic megastar.” That funny epithet is accurate for Byron’s more-than-superstar celebrity in his day. It also suggests the many ways Byron was the opposite of Keats. Miller quotes Byron, in a letter, referring to the younger and much less well-known poet as “Jack Keats or Ketch or whatever his names are.”

Early in her book about John Keats, Lucasta Miller calls Lord Byron an “aristocratic megastar.” That funny epithet is accurate for Byron’s more-than-superstar celebrity in his day. It also suggests the many ways Byron was the opposite of Keats. Miller quotes Byron, in a letter, referring to the younger and much less well-known poet as “Jack Keats or Ketch or whatever his names are.” Around 1987, Sagan gave an uncannily prescient lecture to the Illinois state chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union on the intersection between his area of expertise and theirs. We were fortunate to obtain a recording of that lecture, which we have transcribed, lightly edited, and annotated to update its historical allusions and contemporary relevance. Sagan spoke prophetically of the irrationality that plagued public discourse, the imperative of international cooperation, the dangers posed by advances in technology, and the threats to free speech and democracy in the United States. A 35-year retrospective reveals both increments of progress (some owing to Sagan’s own efforts) and

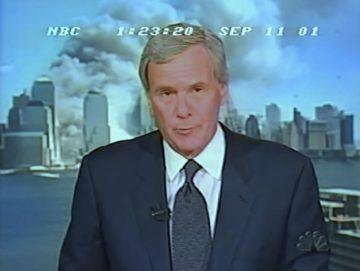

Around 1987, Sagan gave an uncannily prescient lecture to the Illinois state chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union on the intersection between his area of expertise and theirs. We were fortunate to obtain a recording of that lecture, which we have transcribed, lightly edited, and annotated to update its historical allusions and contemporary relevance. Sagan spoke prophetically of the irrationality that plagued public discourse, the imperative of international cooperation, the dangers posed by advances in technology, and the threats to free speech and democracy in the United States. A 35-year retrospective reveals both increments of progress (some owing to Sagan’s own efforts) and If you ask Americans when was the last time they recall feeling truly united as a country, people over the age of thirty will almost certainly point to the aftermath of 9/11. However briefly, everyone was united in grief and anger, and a palpable sense of social solidarity pervaded our communities.

If you ask Americans when was the last time they recall feeling truly united as a country, people over the age of thirty will almost certainly point to the aftermath of 9/11. However briefly, everyone was united in grief and anger, and a palpable sense of social solidarity pervaded our communities. Where You End and I Begin isn’t in fact that book. Instead, it’s something more amorphous, more exposing. It started as a collaboration between the author and her mother but after Cessie withdrew, it ceased being a journalistic investigation into the Horseman and his crimes (there were other child victims) and became an intimate voyage into the deepest, darkest heart of motherhood and daughterhood, musing too on consent, victim narratives and the ownership of stories. The result is a work of probing insight and undaunted compassion; one that’s fearlessly engrossing, frequently funny and sometimes plain hair-raising.

Where You End and I Begin isn’t in fact that book. Instead, it’s something more amorphous, more exposing. It started as a collaboration between the author and her mother but after Cessie withdrew, it ceased being a journalistic investigation into the Horseman and his crimes (there were other child victims) and became an intimate voyage into the deepest, darkest heart of motherhood and daughterhood, musing too on consent, victim narratives and the ownership of stories. The result is a work of probing insight and undaunted compassion; one that’s fearlessly engrossing, frequently funny and sometimes plain hair-raising. During the final months of the Second World War, the publisher Alfred A. Knopf commissioned a reader’s report, consisting of a form on blue paper with a few queries, regarding a translated novel it was considering by an Icelander named Halldór Laxness. Section B of the form instructed the reader, “If you recommend us to publish the book give your chief reason in a single sentence.” The reader replied, “Those who read this book will never forget it.”

During the final months of the Second World War, the publisher Alfred A. Knopf commissioned a reader’s report, consisting of a form on blue paper with a few queries, regarding a translated novel it was considering by an Icelander named Halldór Laxness. Section B of the form instructed the reader, “If you recommend us to publish the book give your chief reason in a single sentence.” The reader replied, “Those who read this book will never forget it.” Why is it that we may agree in advance that a particular result is a fair test of our theory, then see so much more when the result is known? Why can’t we anticipate our response to results that we do not expect to materialize? The psychology of this is straightforward. The normal flow of reasoning is forward from what you believe to a possible consequence. When someone proposes a serious critical test, you cannot get from your theory to the result without adding an extra wrinkle to the theory. The extra wrinkle is hard to find—if it were easy, this would not be a serious critical test. On the other hand, the result probably follows from the adversary’s theory. The lazy solution is to concede provisionally.

Why is it that we may agree in advance that a particular result is a fair test of our theory, then see so much more when the result is known? Why can’t we anticipate our response to results that we do not expect to materialize? The psychology of this is straightforward. The normal flow of reasoning is forward from what you believe to a possible consequence. When someone proposes a serious critical test, you cannot get from your theory to the result without adding an extra wrinkle to the theory. The extra wrinkle is hard to find—if it were easy, this would not be a serious critical test. On the other hand, the result probably follows from the adversary’s theory. The lazy solution is to concede provisionally. Natural immunity induced by infection with SARS-CoV-2 provides a strong shield against reinfection by a pre-Omicron variant for 16 months or longer, according to a study

Natural immunity induced by infection with SARS-CoV-2 provides a strong shield against reinfection by a pre-Omicron variant for 16 months or longer, according to a study IN 2014, the novelist and essayist Cynthia Ozick reviewed the collected fiction of Bernard Malamud for the New York Times. Ozick adores her slightly older contemporary for his bruised moral seriousness. The essay contains just one asterisk: “The reviewer has not read and is not likely ever to read ‘The Natural,’ a baseball novel said to incorporate a mythical theme. Myth may be myth, but baseball is still baseball, so never mind.”

IN 2014, the novelist and essayist Cynthia Ozick reviewed the collected fiction of Bernard Malamud for the New York Times. Ozick adores her slightly older contemporary for his bruised moral seriousness. The essay contains just one asterisk: “The reviewer has not read and is not likely ever to read ‘The Natural,’ a baseball novel said to incorporate a mythical theme. Myth may be myth, but baseball is still baseball, so never mind.” Fallacy though it may be to imagine the narrator of a verse as equivalent with the poet, it’s impossible not to imagine the words of Robert Frost read in that clipped Yankee-via-San-Francisco accent of his, to intuit the blistering cold of a New Hampshire morning or the blinding whiteness of the snow-covered Franconia Range, the damp exertion of sweat under a flannel collar and muddy boots trudging across yellow and brown leaves slick with early morning ice. Frost is forever a poet of loose coffee grounds dumped into boiling water and intricate blue and red quilts, of wooden spoons hanging from hooks next to gas stoves and of curved glass hurricane lamps, of creaking wooden floorboards and doors swollen with summer’s humidity. Visiting his white clapboard, gable-peeked farmstead in Derry, New Hampshire, and perambulating in the golden woods of sugar maple and red oak and it’s hard not to romanticize the old man, eyeing him along the rough granite stone wall that he mended every spring, the famous structure whereby “Good fences make good neighbors,” which he wrote about in his 1914 collection

Fallacy though it may be to imagine the narrator of a verse as equivalent with the poet, it’s impossible not to imagine the words of Robert Frost read in that clipped Yankee-via-San-Francisco accent of his, to intuit the blistering cold of a New Hampshire morning or the blinding whiteness of the snow-covered Franconia Range, the damp exertion of sweat under a flannel collar and muddy boots trudging across yellow and brown leaves slick with early morning ice. Frost is forever a poet of loose coffee grounds dumped into boiling water and intricate blue and red quilts, of wooden spoons hanging from hooks next to gas stoves and of curved glass hurricane lamps, of creaking wooden floorboards and doors swollen with summer’s humidity. Visiting his white clapboard, gable-peeked farmstead in Derry, New Hampshire, and perambulating in the golden woods of sugar maple and red oak and it’s hard not to romanticize the old man, eyeing him along the rough granite stone wall that he mended every spring, the famous structure whereby “Good fences make good neighbors,” which he wrote about in his 1914 collection  This remark, like many of Wittgenstein’s, seems to arise from self-examination. The answer he gives suggests that he is concerned with learning just by thinking, and indeed with the particular kind of learning just by thinking that happens in philosophy (as opposed to, say, mathematics). He seems to be asking how such learning is even possible. What are we to make of his answer?

This remark, like many of Wittgenstein’s, seems to arise from self-examination. The answer he gives suggests that he is concerned with learning just by thinking, and indeed with the particular kind of learning just by thinking that happens in philosophy (as opposed to, say, mathematics). He seems to be asking how such learning is even possible. What are we to make of his answer? At the centre of the Earth, a giant sphere of solid iron is slowly swelling. This is the inner core and scientists have recently uncovered intriguing evidence that suggests its birth half a billion years ago may have played a key role in the evolution of life on Earth.

At the centre of the Earth, a giant sphere of solid iron is slowly swelling. This is the inner core and scientists have recently uncovered intriguing evidence that suggests its birth half a billion years ago may have played a key role in the evolution of life on Earth. I’ve been writing a series of posts about economic development. The last 20 years have seen a marked acceleration in the rate at which poorer countries — not just China, but many countries — are

I’ve been writing a series of posts about economic development. The last 20 years have seen a marked acceleration in the rate at which poorer countries — not just China, but many countries — are  In Laurence Sterne’s 1759 novel

In Laurence Sterne’s 1759 novel  Julia Strand was confident in her scientific findings when they were published in 2018. Strand’s research showed that when a circular beacon of light was present in a noisy setting, people expended less energy listening to their conversation partner and responded quicker than without the light. The feedback was positive and Strand, an associate professor of psychology at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota, had received grant funding to continue her research. Some months later, however, Strand was unable to replicate her results. In fact, she found the opposite to be true: The light forced people to think harder. Strand had crossed her t’s, dotted her i’s, and showed her work — and still she was wrong. “The bottom dropped out of my stomach,” Strand says. “It was terrible to realize that I had not just made a mistake, but published a mistake.”

Julia Strand was confident in her scientific findings when they were published in 2018. Strand’s research showed that when a circular beacon of light was present in a noisy setting, people expended less energy listening to their conversation partner and responded quicker than without the light. The feedback was positive and Strand, an associate professor of psychology at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota, had received grant funding to continue her research. Some months later, however, Strand was unable to replicate her results. In fact, she found the opposite to be true: The light forced people to think harder. Strand had crossed her t’s, dotted her i’s, and showed her work — and still she was wrong. “The bottom dropped out of my stomach,” Strand says. “It was terrible to realize that I had not just made a mistake, but published a mistake.”